Just a couple of short blocks away from the Vega, Moreno, and Ludeña houses is Balingaság’s old parish church. This is evidently a very old structure, although I was unable to find any markers anywhere indicating when it was built or any other information about it.

Subsequently, however, I came across a book, Wood & Stone: For God's Greater Glory by Rene B. Javellana, S.J. (Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1991), which identified this church as a Jesuit-built structure, began in the late 19th century after the Jesuits returned to the Philippines. According to Javellana, the church was constructed progressively over several decades until 1899, when the Revolution caused all work to halt. By this time, the brick wall had reached "a considerable height."

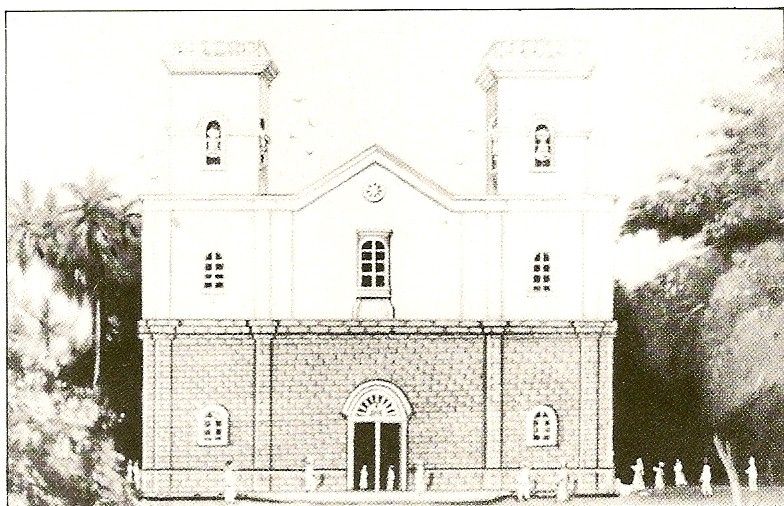

Presumably, work on the church was resumed when the American Jesuits took over, as this archival illustration (also from Javellana) seems to show.

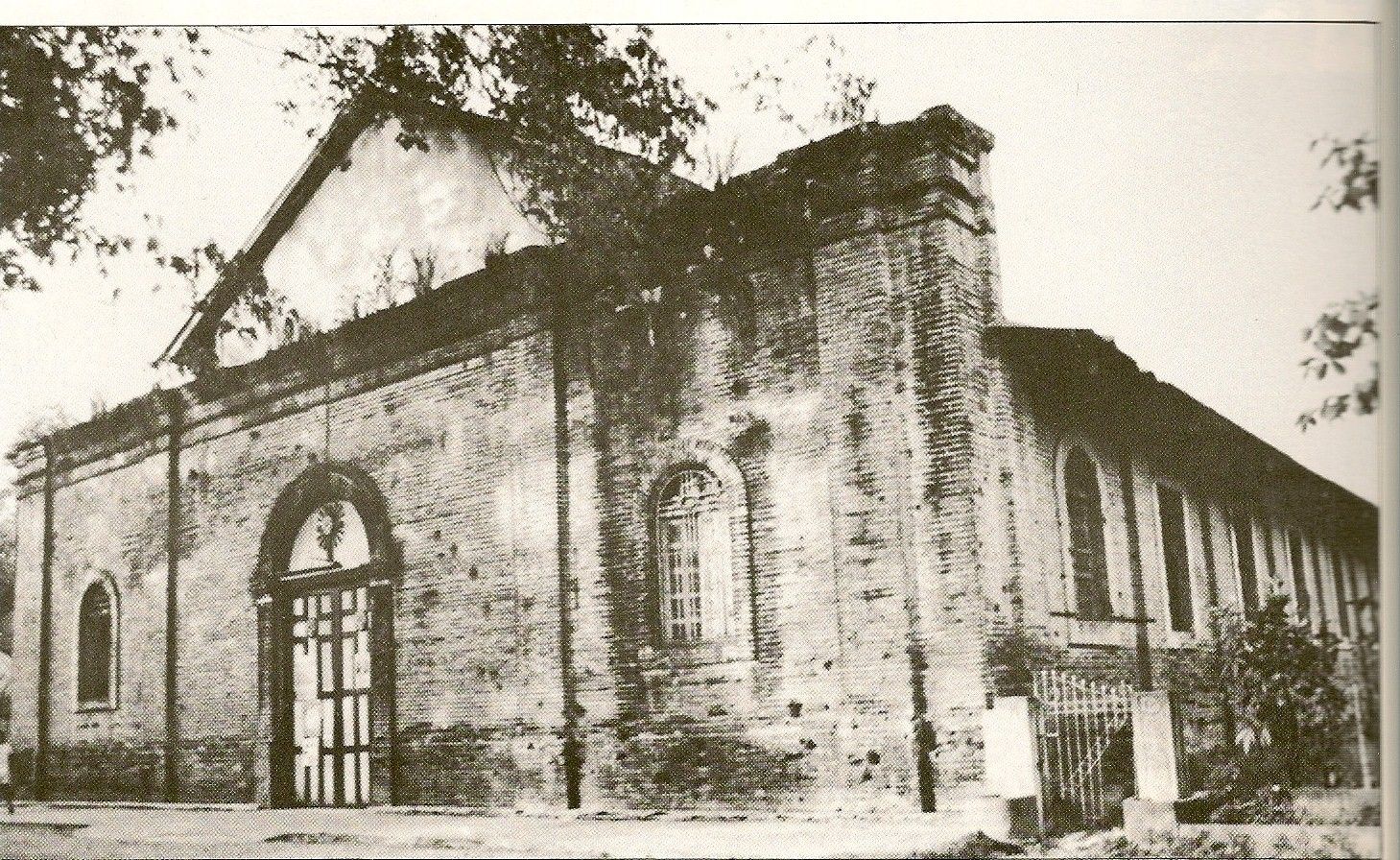

Further information about this church from Javellana: "After the Second World War, all that was left of Balingasag church was the lower story of brick. A temporary roof was built to enable the holding of services, until a more permanent roof of galvanized sheets was installed. The second story, however, was never rebuilt -- thus truncating the structure and giving it a squat and ungainly appearance...." Here is an archival photograph of the structure apparently taken shortly after World War II.

Today, the church is unfortunately still pretty "ungainly," as the following photo of its all-brick façade show.

Today, the church is unfortunately still pretty "ungainly," as the following photo of its all-brick façade show.

I restrain myself from showing you more than the main doorway and the arch overhead

and this old brick-lined window.

The bell tower is a new structure, clad with modern ceramic tiles presumably to ape the antique brick church building.

This does double duty as a four-storey parish office and perhaps even convento.

Inside the nave, the non-rebuilding of the pre-war roof structure has necessitated the use of a hyper-modern ceiling that not only brings in lots of natural light, but also throws out all of the colonial-era charm that this structure most probably had originally.

An alcove by the entrance evidences unfinished remodeling work.

On the opposite side of the entrance is dumped what appears to be the old baptismal font, now missing most of its stem.

Fortunately, the original windows are largely intact, and the thickness of the original walls can still be clearly seen thereby.

The current altar is now thoroughly modern, without a trace of what we might presume was the pre-war Spanish colonial-style retablo with multiple tiers and niches.

However, the light-bearing angels on either side are gracefully old and continue to render service.

According to Javellana, many of the images in this church are antique, and appear to be works of Manila's 19th century (or early 20th century) workshops. For instance, the side altars are occupied by what appear to be such antique images – a Sacred Heart on the left

and an Immaculate Conception on the right.

To the right of the altar is also a Santo Entierro, which looks relatively recent but is not too badly done.

The open eyes and straight arms are clues to the possibility of this being a “convertible” corpus.

This bench for assorted lectors, commentators, and Eucharistic ministers might double as altar seating for a betrothed couple in a wedding ceremony. (And since there were several such love seats in the first row, they can even hold a mass wedding if they wanted to.)

Surrounding the congregation and positioned in each deep window niche in a very utilitarian fashion were several quite noteworthy images, most of which look antique or old, and are generally well-crafted.

There was what appeared to be an image of Saint Louis Gonzaga (or some other sainted priest with a crucifix).

There was another Sacred Heart, this one glossily painted,

a Saint Anthony of Padua with a fallen halo,

a Saint Peter with a flamboyant yellow cloak,

Saint Jude Thaddeus, missing his breast medallion,

Saint Roch with his trusty dog,

another Immaculate Conception,

Saint Rita of Cascia, the town’s patroness,

Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal, with droopy rays,

a pretty well-rendered Our Lady of Mount Carmel,

a Pieta with admittedly realistic rigor mortis,

Saint Isidore the Farmer, lest we forgot that this is after all an agricultural community.

and finally, an appropriately modern-styled San Lorenzo Ruiz de Manila.

This saint-loving community is even better-served that we would think from seeing those images, because lining the walls of the church interior and positioned in between the windows is one of the most impressive Stations of the Cross sets that I have ever seen. According to Javellana, these were commissioned in 1964 by the then parish priest, Father John Pollock.

It starts off with “Jesus is Condemned to Death” featuring a clean-shaven Pilate and a long-bearded High Priest Caiaphas (or Annas).

The entire series is carved in wood, painted in lively colors, and rendered in high relief in a generous scale of roughly a foot and a half.

Not only are the individual characters sensitively rendered, but the artist had also given some thought to the painted background of each scene, as in the Second Station, “The Cross is Laid on Jesus.”

Some full-sized processional tableaux elsewhere in the Philippines might learn a thing or two on blocking and staging by examining the Third Station, "Jesus Falls the First Time."

Even minor nameless characters in the narrative are paid close attention to, as with the Fourth Station, “Jesus Meets His Afflicted Mother.”

A minor grammatical lapse (actually a missing verb) does not throw off the artist in the Fifth Station, “Jesus Assisted by the Cyrenean.”

We take a profile shot of this station to see just how deep these high reliefs – actually already almost full sculptures – really are.

Not being a scriptural scene, there is some awkwardness in how precisely to refer to the piece of cloth in the Sixth Station, “Veronica Presents the Towel to Jesus.”

The last Station on the left side of the nave is the Seventh, “Jesus Falls the Second Time.”

The first Station on the right, though unnumbered and uncaptioned, is the Eighth, “Jesus Meets the Women of Jerusalem.”

I could not take photos of the Tenth and Eleventh Stations as there were several parishioners kneeling, deep in prayer, in the places from where I would need to take the shots. Moving right along then, I proceed to the Twelfth Station, a most classically-rendered “Jesus Dies on the Cross.”

Another missing verb, a lot of dust, and the usual high level of artistry characterize the Thirteenth Station, “Jesus Taken Down from the Cross.”

The series ends predictably with the Fourteenth Station, “Jesus is Laid in the Tomb,” complete with requisite verb.

Despite the current unrestored-to-original-state of this colonial structure, the Balingaság Parish Church is thus fortunate in retaining a very respectable collection of religious images, of which the star of the collection is, perhaps unusually, this formidable set of Stations of the Cross. Here’s hoping that that all these are treasured and well cared for by this pious community in the decades and centuries to come.

Continued here.

Originally published on 5 October 2008. All text and photos copyright ©2008 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Original comments:

johnada wrote on Oct 31, '08

The treasure of this church are the stations of the cross. Quite like the set in Carcar, but in Spanish

|

rally65 wrote on Oct 31, '08, edited on Mar 23, '09

johnada said

The treasure of this church are the stations of the cross. Quite like the set in Carcar, but in Spanish

I have subsequently discovered that the Stations of the Cross date from 1964. Please read the edited article text.

|

jsfrom wrote on Oct 31, '08

Thanks for another informative and colorful tour. I certainly miss home. I am sorry I could not share at the moment. I will try one of these days.

|

rally65 wrote on Mar 23, '09

While convalescing during a recent nasty bout with the flu, I came across a 1991 book, Wood & Stone: For God's Greater Glory, which identified this church as a late-Spanish-colonial-period Jesuit structure, and provided plenty of other useful information besides.

I have thus edited the article for these newly-surfaced bits of information (mainly that the church was not actually deliberately "modernized," and that the Stations of the Cross date from 1964). Please reread it now. |

No comments:

Post a Comment