The Akyat-Bahay correspondent in Cebu

(and certified santo addict) Louie Nacorda very kindly made transport

arrangements and introductions so that I could spend an entire day in the town

of Carcar, about 40 kilometers (and the better part of an hour or so) south of

Cebu City. Having done rudimentary

research beforehand, I already knew that the town had a promising array of

heritage structures for my first-hand examination, with the only obstacle being

the fact that I had never been in this town before and I did not even speak the

local language. But that never stopped

me before!

Having been given general directions, I

did not have much difficulty in locating my target.

Before motoring down to Carcar, however,

I dug up some information about my first akyat-bahay target of the day, partly courtesy also of Mr.

Nacorda. The Don Florencio Noel and Doña Filomena Jaen House was

originally owned by spouses Jacinto Aldocente and Benita del Corro and

purchased by Don Florencio on 27th January 1873 for the princely sum

of 160 pesos. However, the document of

sale described the house as “tabla y nipa” and not the structure of coral stone

and hardwood surviving today. Therefore,

Don Florencio must have completely built or rebuilt it, presumably shortly

after the acquisition. There is even

documentation of the names of the master craftsmen who worked on the 1873

structure: Segundo Alesna (carpenter, Carcar), Críspulo Zábate (carpenter, born

in San Nicolás, resident of Carcar), Celestino Sarmiento (carpenter, born in

Cebu City, resident of Carcar), Lito [?] Alesna (mason and carpenter, Carcar),

Pelagio Gutiérrez (stone-cutter).

Walking slightly further on gives one a

nice full-frontal view of the large house created by these master craftsmen,

with a typical extension for an azotea

to the right

Excluding the azotea momentarily, the

façade was beautifully balanced,

with large arched-top doorways on either

side of a barred square window.

After wagering that the real main

entrance would probably not be this set of wooden plank doors on the right side

of the façade, with an outside lock

but rather this other set on the left

surmounted by a blue tile of the Sacred Heart and Immaculate Heart, and with a

postigo (cut-out pedestrian doorway),

I knocked and made some noise outside this,

and – abracadabra – the postigo opened itself for me.

Actually, the door was opened for me by

the current homeowner, Jerry Martin Noel Alfafara, whom Louie had also put me

in contact with. Mr. Alfafara was raised,

educated, and had worked in the United States, but some years before my visit,

he uprooted himself from Chicago and came home to Carcar to take possession of

this ancestral house that he inherited from his mother’s family. He conversed with everyone (except me of

course) in fluent Cebuano (though with a strong American accent), which

indicated to me that he was completely at home and committed to staying put.

After shutting the entrance behind us,

he led me through the ground-floor foyer

which gave me an opportunity to

appreciate the original coral stone walls

wooden ceilings

and well-worn granite floors

There was, on one wall, a door that led

to the rest of the ground floor, the bodega that could also be accessed via the

locked door on the right side of the façade that we had seen from the outside

earlier.

There was no significant attempt to

disguise the tree trunks that actually hold up the house’s second floor and that

lined up with the non-load-bearing stone walls.

At the end of the foyer was an

intermediate stone landing

where an apparently much-used wicker

seating set was positioned.

From this landing, the visitor could

view the property’s side yard

through iron grilles (and beside an

image of Carcar’s patroness, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, painted on a capiz

window panel)

Finally, we were ready to ascend the

house’s grand staircase

but not before we are distracted by yet

another door,

that gives access to another part of the

ground floor, likely the home office of the original master of the house (and

his successors).

We finally make it to the top of the

grand staircase

which is a beautifully symmetric

showpiece of turned balusters and carved newel posts from the house’s

aforementioned master carpenters.

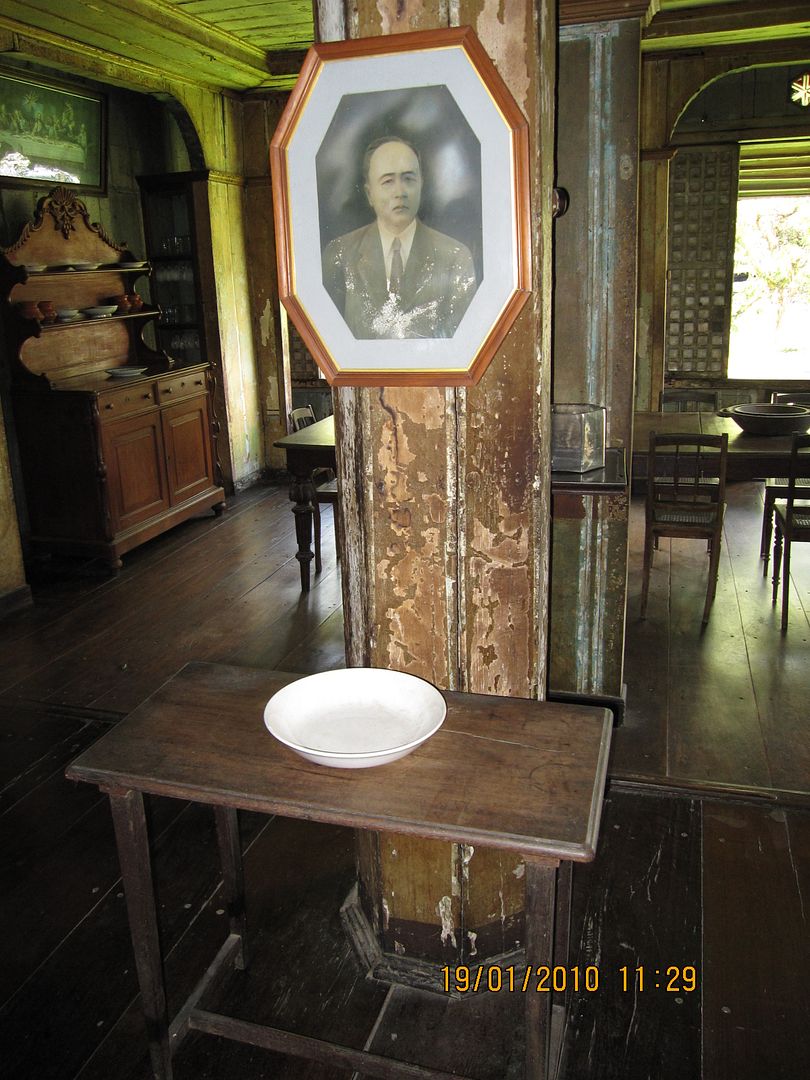

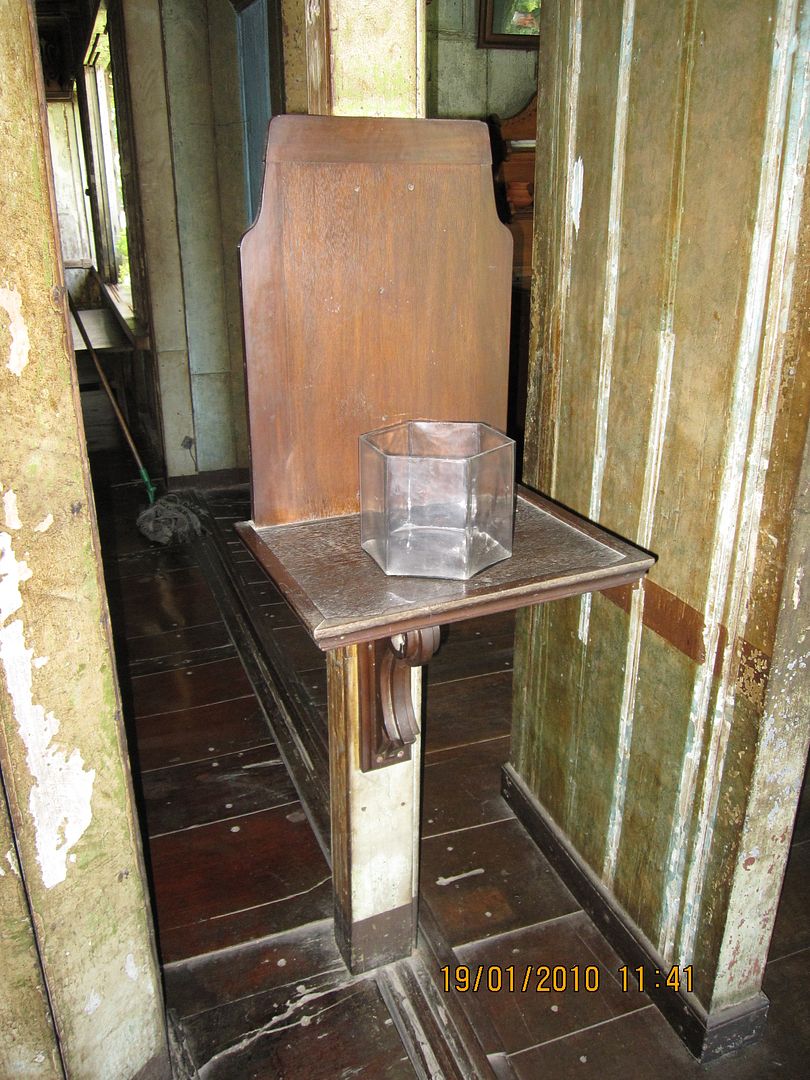

Upon emergence from the staircase, the

visitor is greeted with what might have been intended to be a washbasin on a

small console table, underneath a portrait of an earlier resident hanging from

a post.

And in the distance may be seen a

lansena to the left and a long dining table to the right, of which more later.

On the left side of this antesala or

entrance hall is a long hallway with a doorway to one bedroom on its left

and a seating area in the far distance,

beside a louvered divider.

We look up to appreciate the

geometrically decorated ceiling in this area.

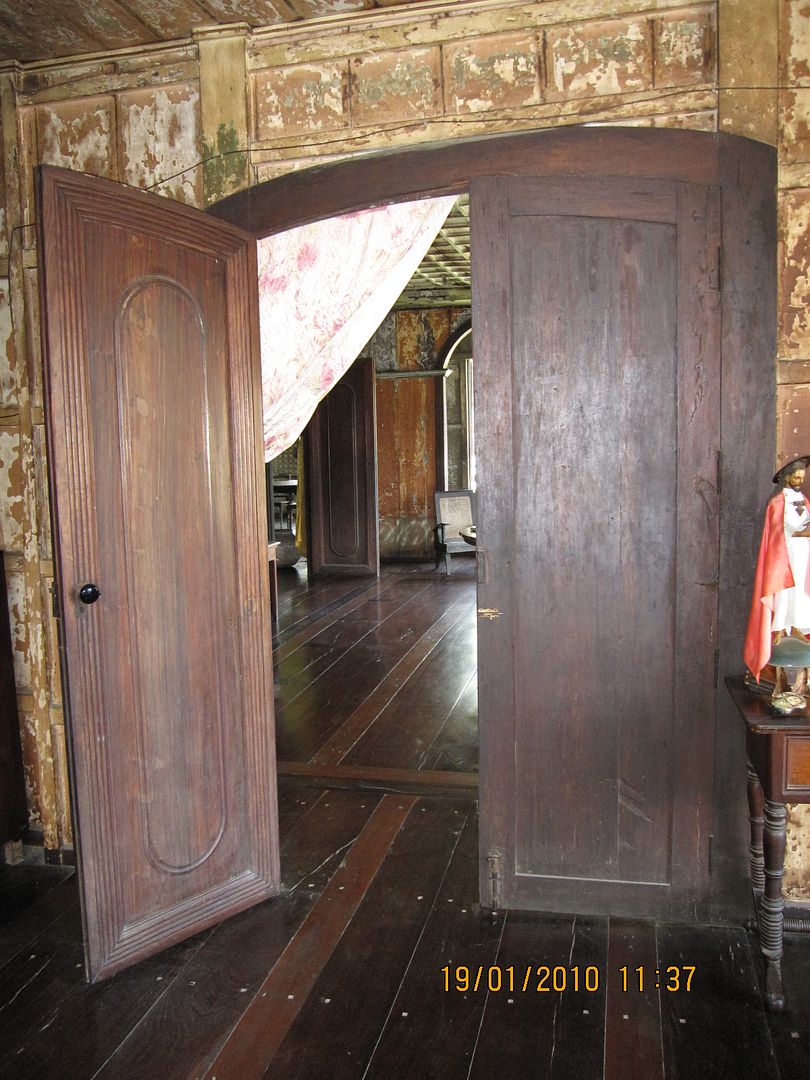

Turning to the other (right) side of

this entrance hall, we are welcomed by yellow curtains over a beautifully

carved doorway

framing a gently arched pair of doors

to the sala or main living room

that looked over the main road in front

of the house, via a narrow “volada” or flying corridor.

The living room floor was made up of a

variety of wooden planks, perhaps balayong and narra,

and edged with reinforcements of some

sort in kamagong.

This living room held furniture from

different periods in the house’s long life, including a post-war ambassador

sala set

a small single-drawer table in one

corner

another similar table beside the doorway

and under another portrait

and a bentwood set.

There was also a nice pair of

non-identical console tables opposite each other, one against a post and

marble-topped

and the other all-wood against the

opposite wall

and under a Venetian-style mirror

The living room was illuminated by a

single chandelier hanging from a ceiling of squares of about a foot each.

From this living room, the master of the

house could enter his bedroom via double doors

similar to those of the entrance from the

antesala, and that look like this from the inside.

This master bedroom is prominently

positioned at the corner of the house, overlooking the main street and the side

yard, and is directly above the main entrance.

It features a beautifully ornate Ah Tay-style canopied bed

and a late 19th century

tambol aparador, also in the Ah Tay-style.

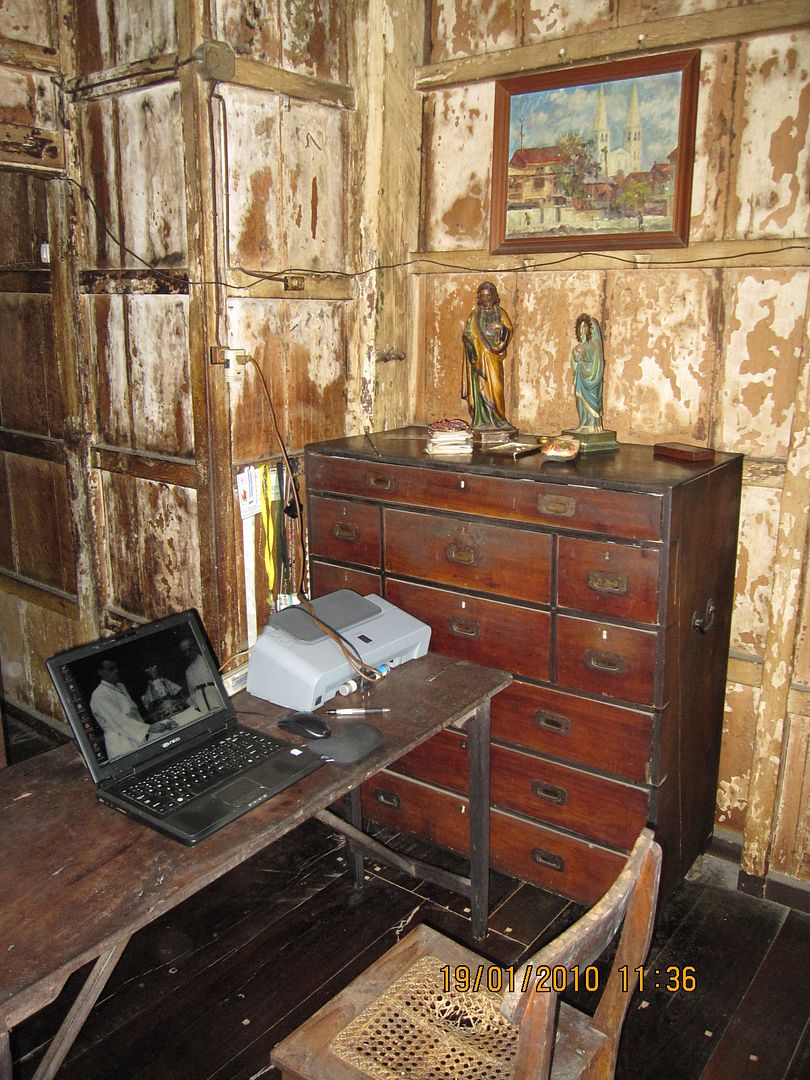

There was also another aparador in an

early 20th century style, generously carved and mirrored,

a chair and small table

and a makeshift home office desk and

chair beside a chest of drawers.

Finally, there was a trio of Santos – a

Sacred Heart, a Saint Vincent Ferrer, and a Blessed Virgin Mary –

on a small two-drawer altar table.

Going back outside to the antesala, we

make our way to the large dining room,

directly opposite the grand staircase.

Behind the pillar that we had seen earlier

and sandwiched in between it and the dining room wall was this permanently

fixed table

perhaps originally intended to work as a

plant stand, or maybe a serving table.

At one end of this dining room was this

beautifully carved 19th century lansena or sideboard that we had

glanced at when we first came up the stairs.

On either side of this lansena were

these built-in cupboards that held plateware and glassware.

However, the main feature of this 19th

century dining room was undoubtedly this long dining table.

Long-time readers will immediately

recognize this as a magic table,

in an unusual and rare (but apparently

not for this house) Ah Tay style.

Rather than individual free-standing

segments as with most other Filipino magic tables, this was of the type where

two end tables

supported one long legless middle

stretch, providing comfortable seating for twelve or more diners.

Lighting was provided by this

etched-milkglass Art Deco fixture

and by the bright sunshine through these

pair of doors decorated with glazed hexagons

from the open balcony

directly between the dining room and the

main road outside, from where one can peep into the living room

or glance back into the dining room

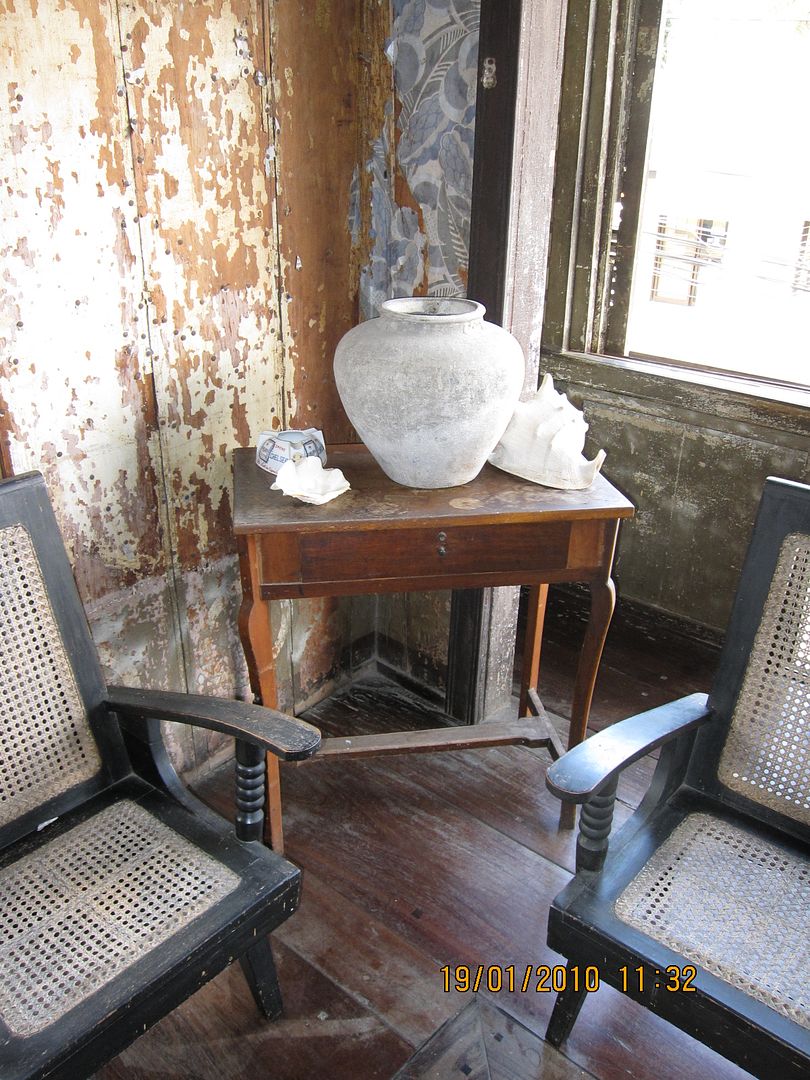

Back in the antesala, we walk to the far

end,

to the seating area that we saw earlier,

which has not only a table and chairs

but also a window-side bench.

and colourful artworks such as this one.

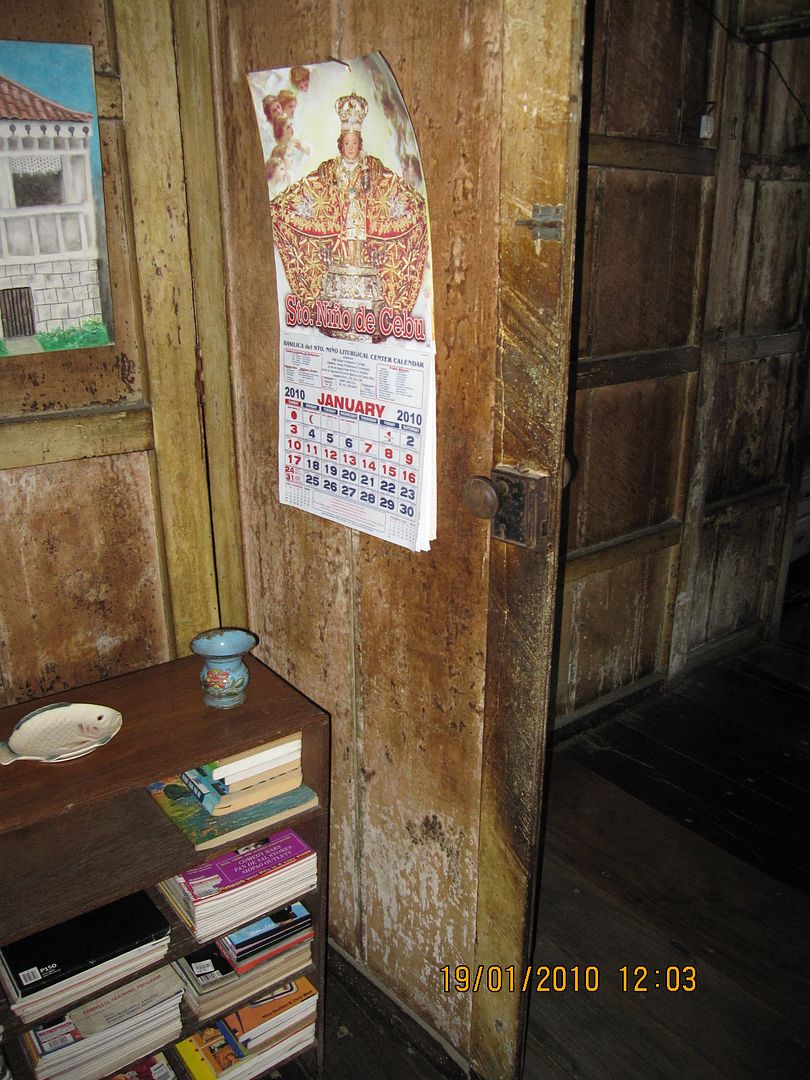

One bedroom was accessed from this

hallway via these double doors.

This bedroom was well supported from

underneath by yet more undisguised tree trunks.

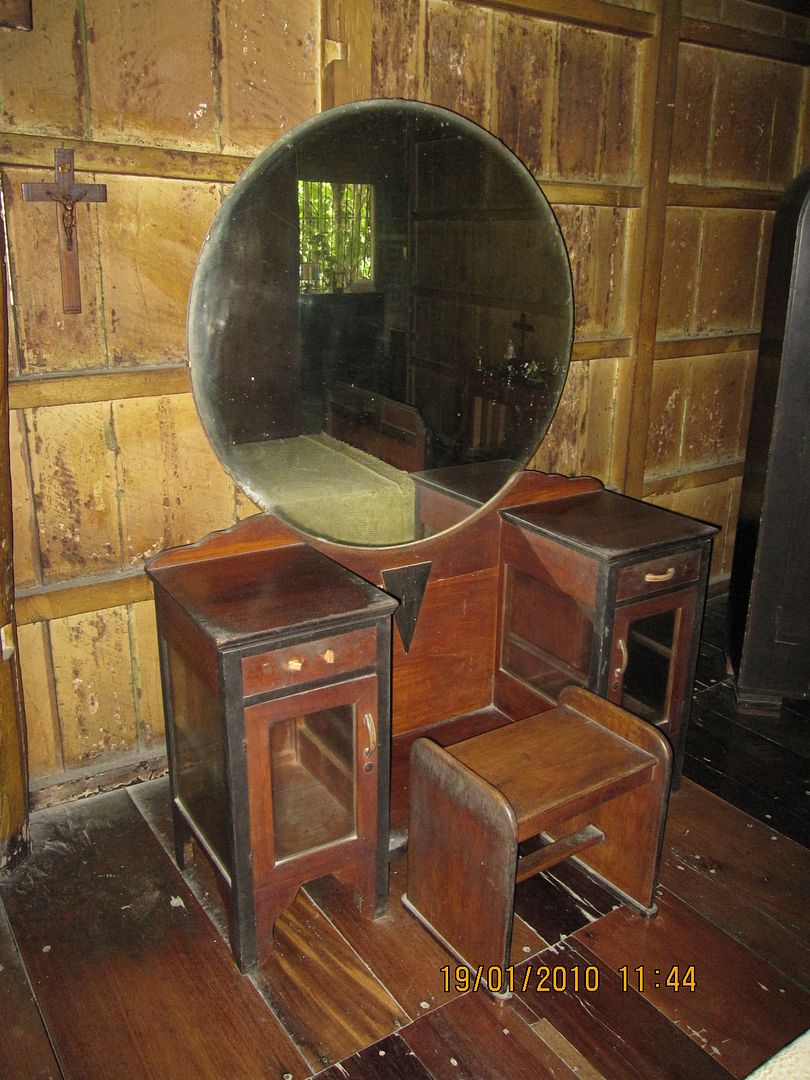

In contrast to the master bedroom that

we had already visited, this had more recent furnishings from the 1930’s,

including this Art Deco bed,

this full-moon-mirrored Art Deco dresser

and this asymmetric aparador.

On the other hand, there was also a 19th

century tambol aparador

now missing its crown plinth, an

iron-framed bed, possibly from around the turn-of-the-20th century

and a curious-looking freestanding

cabinet with indeterminate function (was it a safe?).

Back in the hallway, we go past the

louvered divider, now missing several teeth,

to check out the house’s third bedroom,

behind yet another set of double doors.

This bedroom had another iron-framed bed

and another two-door tambol aparador.

There was also a low chest of drawers,

apparently with a marble top, under a wood-framed mirror.

And in one corner was a tall double-door

aparador, which looked built-in.

Back outside this bedroom, there is a

small corridor

from where on the left side is a small

doorway that leads back to the second bedroom,

and from the right side is another set

of double doors that that gives access to a fourth bedroom, actually beside the

third bedroom.

This bedroom had yet another iron bed,

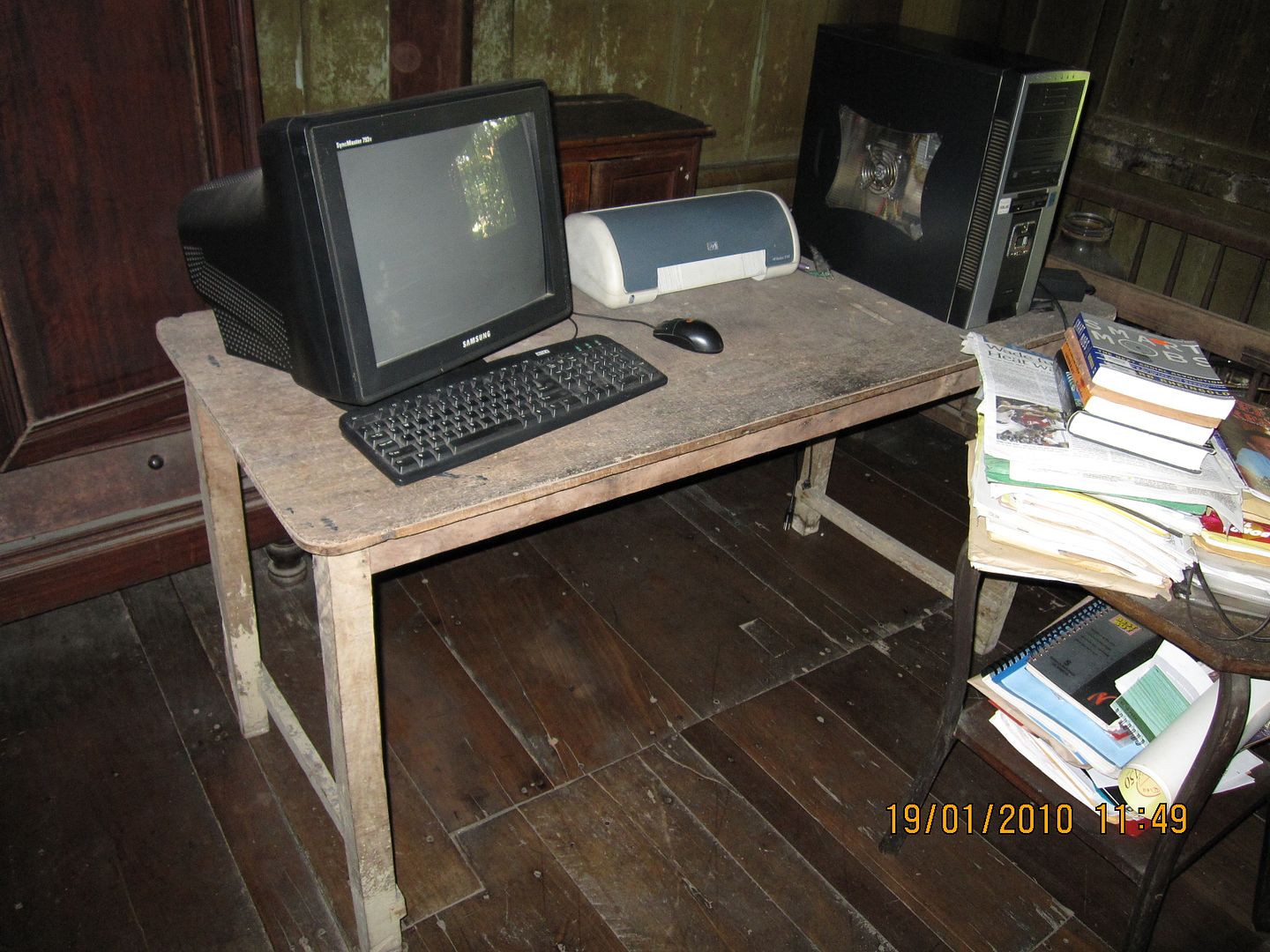

a low two-door tambol aparador,

a crib, presumably now outgrown,

and a makeshift home office work station

At the far end of this small corridor is

a wide single-leaf door

that leads to a large kitchen and work

room, featuring a small platera

beside another tree trunk pillar,

and another one,

a table and benches,

and various other practical tables and

cabinets,

including a chicken coop (with no

residents at this time).

One needs to get over the distressed

walls,

and rough or cratered floors

to get to the massive firewood-fuelled

stove

or to use the rudimentary facilities

or simply to seek fresher air outside.

If one wishes to use somewhat better

facilities, there is fortunately a secret room tucked in between the master

bedroom and the second bedroom, accessed via these doors above the main

staircase,

This room not only contains further pieces

of furniture, including another double-door aparador

and a low comoda.

Hidden deep inside this room

is the master toilet-bath, likely a 20th

century add-on.

This lengthy old-house exploration made

me ripe and ready for my host’s generous offer to walk to the nearby public

market to pick up some very fresh lechon and sitsaron (Carcar’s specialities)

and vegetables (edible ferns), which we brought back to the house and feasted

on while seated at the Ah Tay magic table in the dining room. But since this is not a food blog, I’ll fast

forward through this.

Right after lunch, my host took me to

just about the only part of the house that I had not seen (or so he said) –

another bedroom at the back, near the kitchen,

which now functioned as a storeroom for

some elderly residents, including what was said to be Carcar’s original processional

image of its patroness, Saint Catherine of Alexandria

and her traditional emblem, the breaking

wheel on which she is believed to have been martyred.

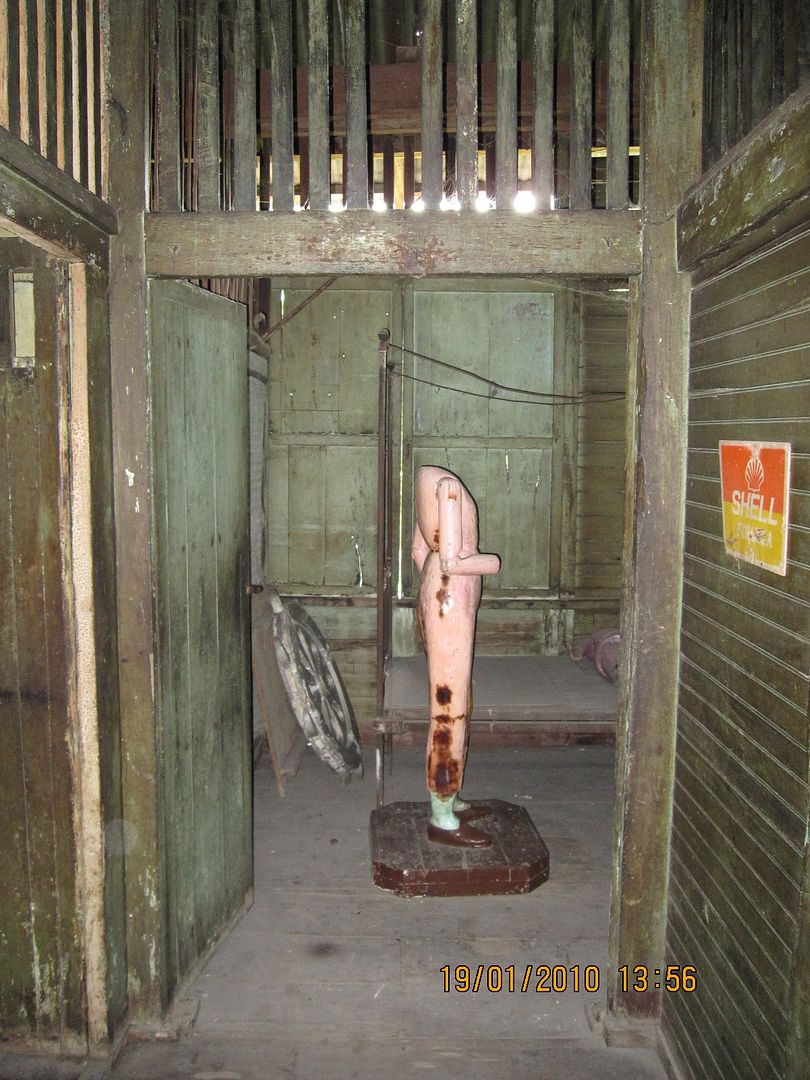

There was also what was obviously a

Nazareno, apparently of more recent vintage,

a couple of unidentified torsos,

and numerous smaller images, mostly from

a now-incomplete Nativity tableau.

Obviously these images would benefit

from a thorough restoration. Which will

be easy compared to the restoration needed by the 1873 Florencio Noel and Filomena

Jaen Ancestral House. Mr. Jerry Martin

Noel Alfafara needs all our appreciation and best wishes on this challenging

yet very worthy endeavor.

Originally published on 16 April 2018. All text and photos (except where attributed otherwise) copyright ©2018 Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Originally published on 16 April 2018. All text and photos (except where attributed otherwise) copyright ©2018 Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.