We’ve already started Holy Week, and in the

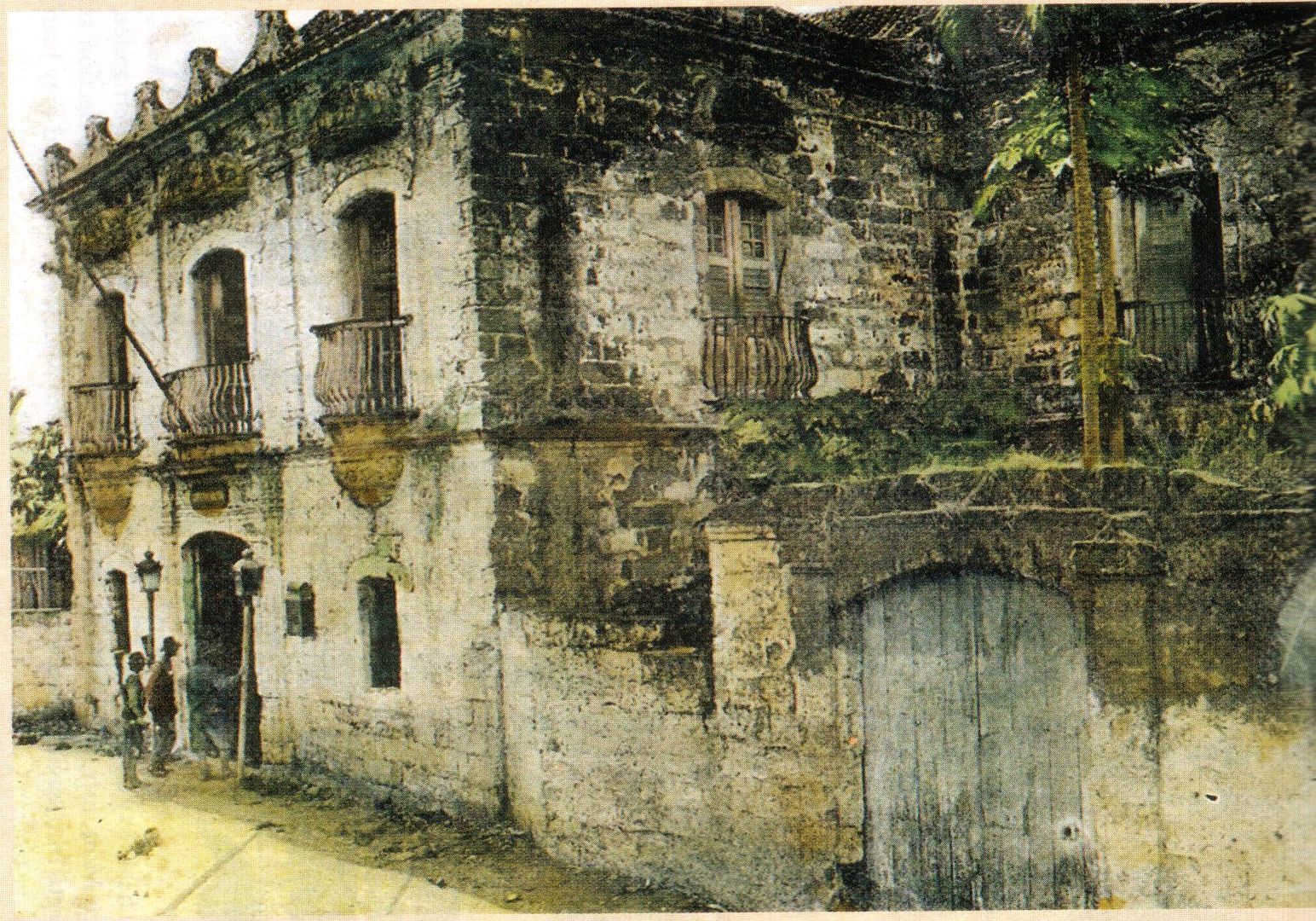

The first milestone in its development is probably the versified narrative of the Passion, beginning with the Last Supper and ending with the Resurrection, authored by Gaspar Aquino de Belen of

Since then, various other editions have appeared, especially in Philippine languages other than Tagalog. By the early post-World War II years, the entire nation was apparently Pasyon-literate in their own regional languages.

The answer is a bit complicated, so let me start with a simple version. No, I have not come across any broadly-published documentary-type field recordings of actual Pasyon chanters in action. This is a pity, because in order to learn how these chants are to be properly sung, it is best to listen to how they were ACTUALLY sung in some home or visita during Holy Week.

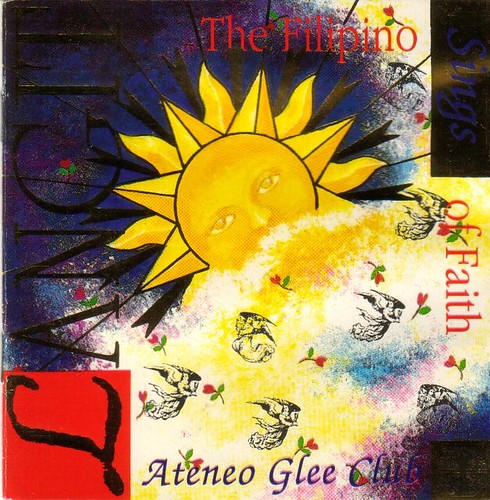

Instead, what is available are a couple of recordings of funky, modernized versions of the Pasyon. The first one of these is inside the album “Langit: The Filipino Sings of Faith” from the Ateneo Glee Club.

There are four short tracks here that are excerpts from the Pasyon text, and do base their music on traditional Pasyon chants. The album opens with “Pagsilang,” using the following stanza from the Pasyon:

There are four short tracks here that are excerpts from the Pasyon text, and do base their music on traditional Pasyon chants. The album opens with “Pagsilang,” using the following stanza from the Pasyon:

Nang malaon nang totoo,

taong maikapat na libo,

mulang lalangin ang mundo

siyang nganing pagparito

niyong sasakop sa tao.

Because it has been arranged for a young modern choir, it is either really refreshing and innovative, or is irritatingly self-conscious and potentially irreverent, depending on your musical taste and religious profile. I recommend listening to “Pagsilang” to see which part of the spectrum of listeners you might be in. If you like what you hear, go ahead with the other tracks such as “Buhay,” “Handog," and “Alay ” as well.

This recording just doesn’t do it for me, as I can’t imagine my family, friends, and fellow parishioners in Bulacan singing anything this way, especially not a religious text for Holy Week, unfortunately.

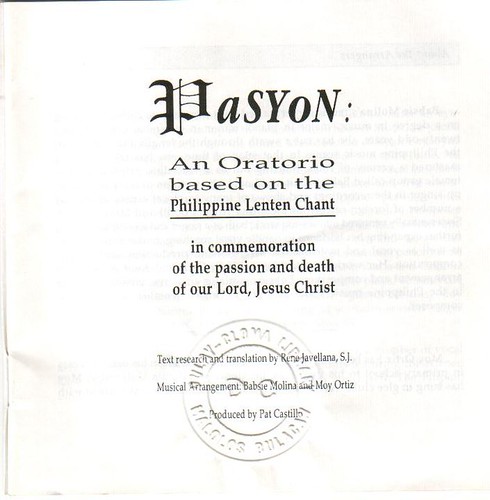

Another creative and innovative effort is the album “Pasyon: An Oratorio based on the Philippine Lenten Chant.”

This makes use of excerpts from the 1703 and 1814 editions to come up with a classical-style oratorio to commemorate the passion and death of the Lord. The text selections highlight the fact that the beauty of Tagalog poetry, even in the earlier-described quintilla format, lay not in rhyme or meter, but in the juxtaposition of either contradictory or complementary images. This compare-and-contrast aesthetic is referred to as “talinghaga” even by modern-day Tagalogs. In “Panalangin,” the first track on this album, we can try to identify what the “matalinghaga” aspects might be:

mulang lalangin ang mundo

siyang nganing pagparito

niyong sasakop sa tao.

Because it has been arranged for a young modern choir, it is either really refreshing and innovative, or is irritatingly self-conscious and potentially irreverent, depending on your musical taste and religious profile. I recommend listening to “Pagsilang” to see which part of the spectrum of listeners you might be in. If you like what you hear, go ahead with the other tracks such as “Buhay,” “Handog," and “

This recording just doesn’t do it for me, as I can’t imagine my family, friends, and fellow parishioners in Bulacan singing anything this way, especially not a religious text for Holy Week, unfortunately.

(the Ateneo Glee Club singing Regina Caeli, an Easter antiphon)

Another creative and innovative effort is the album “Pasyon: An Oratorio based on the Philippine Lenten Chant.”

This makes use of excerpts from the 1703 and 1814 editions to come up with a classical-style oratorio to commemorate the passion and death of the Lord. The text selections highlight the fact that the beauty of Tagalog poetry, even in the earlier-described quintilla format, lay not in rhyme or meter, but in the juxtaposition of either contradictory or complementary images. This compare-and-contrast aesthetic is referred to as “talinghaga” even by modern-day Tagalogs. In “Panalangin,” the first track on this album, we can try to identify what the “matalinghaga” aspects might be:

O Diyos sa kalangitan

hari ng sangkalupaan

Diyos na walang kapantay

mabait, lubhang maalam

at puno ng karunungan,

Ikaw ang amang tibobos

Diyos na walang kapantay

mabait, lubhang maalam

at puno ng karunungan,

Ikaw ang amang tibobos

nang nangungulilang lubos

Amang di matapos-tapos

maawai’t mapagkukop

sa taong lupa’t alabok,

Amang di matapos-tapos

maawai’t mapagkukop

sa taong lupa’t alabok,

Iyong itulot sa amin

Diyos Amang maawain

mangyaring aming dalitin

hirap, sakit at hilahil

ng Anak mong ginigiliw.

Some of the people behind this project were also involved in the “Langit” recording, so musically, the two albums are similar, as the above listening example shows. The basic chants used are of the most common melodies still current today; the production notes credit theprovince of Bulacan

mangyaring aming dalitin

hirap, sakit at hilahil

ng Anak mong ginigiliw.

Some of the people behind this project were also involved in the “Langit” recording, so musically, the two albums are similar, as the above listening example shows. The basic chants used are of the most common melodies still current today; the production notes credit the

Ay ano nga’y nalikmo na

Si Jesus na Poong Ama

Siya sampu ng kasama

Doon sa kakanan nila

At nagwika kapagdaka

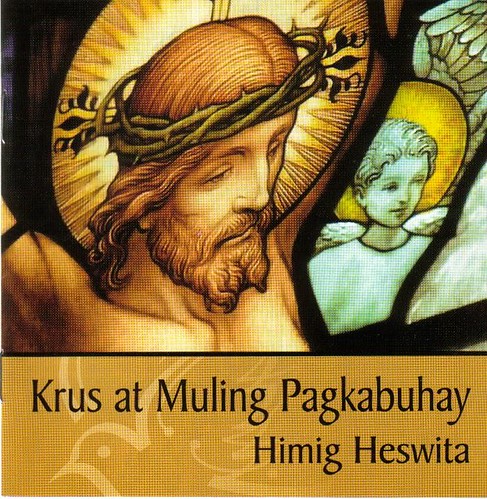

Obviously, this still doesn’t meet our requirements for self-edification. Our last hope is “Krus at Muling Pagkabuhay” from Himig Heswita of the Jesuit Communications Foundation at the Ateneo de Manila University, published in 2003.

Siya sampu ng kasama

Doon sa kakanan nila

At nagwika kapagdaka

Obviously, this still doesn’t meet our requirements for self-edification. Our last hope is “Krus at Muling Pagkabuhay” from Himig Heswita of the Jesuit Communications Foundation at the Ateneo de Manila University, published in 2003.

This promisingly offers fourteen different “Pasyon Himig” (chant melodies), which the authors each characterize as possessing one of several possible qualities: “angkop sa karaniwang salaysay” (appropriate for normal narratives), “angkop sa bahagi ng salaysay na tigib ng hapis” (appropriate for sorrowful parts of the narrative), “angkop sa mga salita ng Panginoon” (appropriate to lines spoken by the Lord), and so on.

Interestingly, the texts used in this recording are not from the old traditional Pasyon texts, but are taken from the “Aklat ng Pagmimisa sa Roma,” or the Roman Missal in Tagalog, published in 1981. This ensures that all its contents are liturgical and orthodox, rather than simply traditional or, worse, folksy.

It then becomes a simple matter of matching up the texts, which cover Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday, to the appropriate chant melodies, as to whether they are meant to be sad, happy, and so forth.

The first two of the fourteen chants are probably the most common, and should be familiar to just about any Holy Week church-goer in at least the Tagalog-speaking regions. In fact, from my childhood listening experience, these two are always used together, with the first used for the odd-numbered Pasyon stanzas, and the second used for the even-numbered ones. Here are the words of Himig 1 and Himig 2 here (even if they’re not arranged in the manner that I’ve just described):

Himig 1

Poong makapangyarihan

Lumikha ng sanlibutan

lupa’y iyong inilagay

nang matatag at matibay

sa tubig ng karagatan

Himig 2

lupa’y iyong inilagay

nang matatag at matibay

sa tubig ng karagatan

Himig 2

Kay Kristo, Haring Mesiyas

Sumalubong nang may galak

Taglay ang manga palaspas

Manga batang iyong anak

Jerusalem

In my view, this is valuable not only because it offers the fourteen different Pasyon chant melodies as previously mentioned, but also because it comes fully documented with a book with complete liturgical texts beyond the ones included in the recording. In fact, beyond the texts set to Pasyon chant, the album includes a “bonus track” at the end, a popular hymn frequently used in the Mass, “Pag-Ibig Mo

Sumalubong nang may galak

Taglay ang manga palaspas

Manga batang iyong anak

In my view, this is valuable not only because it offers the fourteen different Pasyon chant melodies as previously mentioned, but also because it comes fully documented with a book with complete liturgical texts beyond the ones included in the recording. In fact, beyond the texts set to Pasyon chant, the album includes a “bonus track” at the end, a popular hymn frequently used in the Mass, “Pag-

Moreover, the book includes the printed musical notation so that your pianist or organist (or a musically-literate guitarist who can play from musical notes rather than guitar chords) can play the main melody so that the singers can follow, as well as improvise the chordal and bass accompaniment.

I would have, however, preferred to listen to a wider variety of voices, as all of the singers in this album seem to be young, male, and Atenean. This is rather unlike the typical Pasyon singer, who would be older, female, and possibly a full-time homemaker in one of the Tagalog-speaking provinces around

It would also have been better to make use of other accompanying instruments other than a synthesized piano – for example, a normal guitar, or a small electric organ, as this would probably be a more typical accompaniment as well. Or why not even unaccompanied, but harmonized, vocal arrangements, in two, three, or four parts?

My final beef with this recording is that, even with the ubiquitous Himig 1 and Himig 2, the recorded performances are not perfectly accurate – based on my hearing, they’re not the sung in the same way, meter- and beat-wise, as how they are sung even today in Bulacan. And the harmonized accompaniment too is inferior to what is used and played in places like Malolos. Not really being a trained musicologist, I can’t really explain it in precise musical terms, but one only needs to visit

Overall, though, this is a worthy effort and fills a huge gap in our knowledge and understanding of this most important form of Philippine religious music. But we still want to listen to an authentic field recording that documents an actual Pasyon “performance.” It doesn’t have to be the whole eighteen- to twenty-hour saga of the entire Pasyon book, and video is a nice bonus but is not an essential. Hopefully, some day, one such recording will turn up, and it will be a good one too.

Originally published on 18 March 2007. Text copyright ©2007 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted. Musical examples are owned by their respective copyright holders and are used only for review and demonstration purposes.

illuminati1 wrote on Jul 19, '07

thanks for the download and lyrics

|

tandang1 wrote on Feb 1, '08

can u tell me where I can get a downloadable copy of the words of Tagalog Mass please?

You can contact me at kevin@padrepio.org.au |

rally65 wrote on Feb 12, '08

Sorry, I don't actually know where the Tagalog mass text may be downloaded from. I suggest that you try doing an internet search.

|

rally65 wrote on Mar 8, '08

The music for the pasyon himig examples is given in the book. Please try to get the book and look for the chords in there.

|

pabasa2011 wrote on Apr 15, '09

For the benefit of the Filipino children born outside the Philippines do you think it's possible to have the pasyong mahal translated in English? The tradition is brought over here in California (at least) and it will make more sense and perhaps draw their interest (even other nationalities') if they could at least "pray" or "sing-along" with it.

Thanks. |

rally65 wrote on Apr 15, '09

That's certainly a good idea. I just don't know who might be capable of undertaking this initiative (translating musical lyrics from one language to another while retaining "sing-ability" is always a challenge). Hope someone steps forward.

|