Continuing on the seasonal theme of visiting interesting repositories for the dearly-departed, it occurred to me that one of the two houses of worship in Makati that I frequent for weekday masses, the Santuario de San Antonio along McKinley Road (the other is the Chapel of Our Lady of Guadalupe in the basement of BDO Tower 2 at the corner of Makati Avenue and H.V. de la Costa Street) conveniently features perhaps the poshest set of resting places for the deceased.

No, not the three separate structures built to hold the cremated remains of a few hundred moneyed folks, designated as Crypts One, Two, and Three, at the back of the main church in Santuario and next to the three so-called Multi-Purpose Chapels – the Capilla del Señor, the Capilla de la Virgen, and the Capilla de San Antonio – whose own sole purpose seems to be to host the wakes of the wealthy and prominent (or of anyone who can afford the rates).

Because there is another even more posh burial place in the vicinity, right inside the church itself. This is the Zóbel de Ayala Family’s own mortuary chapel, hidden in plain sight, at the left side of the main entrance just behind the façade of the church. As the Ayala family not only originally donated (via the Ayala Corporation, in 1951) the two-hectare land that is now the churchyard, but also must have shouldered a significant part of the construction cost of the church building (completed in 1953), it does not appear inappropriate to allow them to have their own private chapel within the church walls.

Perhaps contrary to expectation, the chapel is unassuming and is therefore very easy to miss. Since it is shrouded in darkness most of the time (except perhaps when family members are present), it is easy to mistake its doorway as the entrance to one of a number of storerooms also frequently seen inside churches all around the world.

What adds to its relative anonymity is that it is not only unmarked, but also has arched and balustered wooden double doors identical to those of the confessional room adjacent to it, making it appear to be just one of those rooms, as it were.

I gingerly pull open the right-side-leaf door, and am relieved to find that it is unlocked.

The chapel is not very large, perhaps not much more than thirty square meters in area, all told. It is configured like a regular chapel, with a marble altar table in front. (And a kneeler -- communion rail? -- in front of the altar table.)

High above the altar table on the wall is a replica of a medieval image of the Blessed Virgin holding the Holy Infant from the town of Alava, Victoria in Northern Spain, to which the Ayala clan traces its roots.

This replica is now venerated as the Nuestra Señora de Ayala, and has on its base the family’s coat of arms.

The image is flanked on each side by pairs of rather modern-styled stained glass windows that sparingly admit light from the church façade into the otherwise pitch-dark chapel.

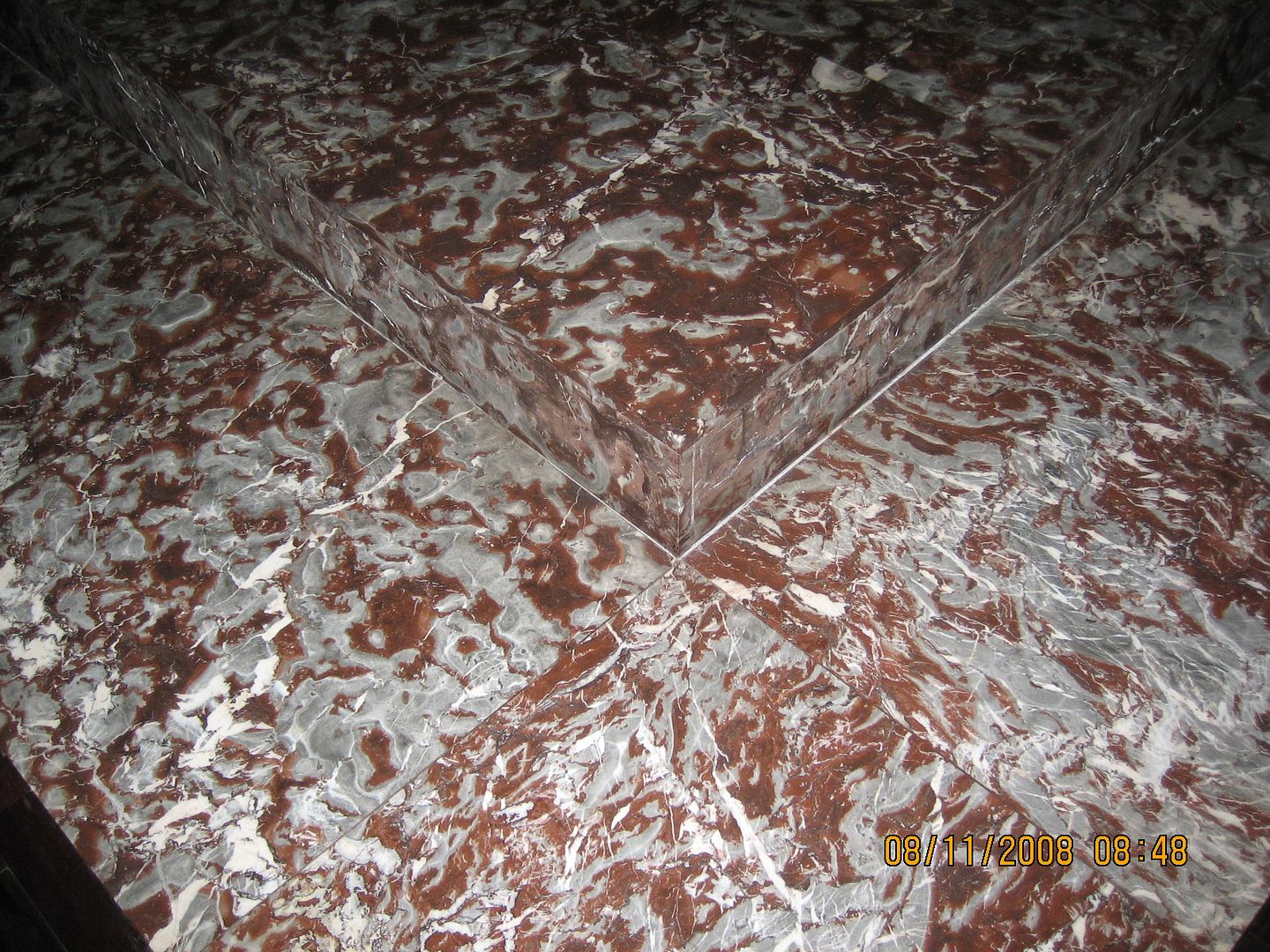

Expectedly first class materials, namely imported, possibly Italian, marble, and Philippine hardwood, had been specified for the chapel floor.

The floor of the altar area, as well as the base of the altar table, features this unusual streaky red-and-gray marble species.

The rest of the floor is in a most impressive tropical hardwood parquet combination of what appears to be rarer-and-harder-than-narra balayong (also known as tindalo), and kamagong (a.k.a. Philippine ebony).

The chapel also features a beamed and coffered ceiling

with an antique style wooden four-bladed ceiling fan, as the cool confines of this corner of the church do not really require airconditioning.

Spotlights are also mounted on the beams above the ceiling fan, the only other source of lighting (apart from the aforementioned four small stained glass windows) in this chapel.

While I could see where the switches were, I chose to keep the lights off, not only to avoid bothering the “residents” but also to keep the entire experience suitably eerie. All my photographs here therefore made use solely of the built-in flash of my nondescript commercial-grade point-and-shoot camera.

There were two rows of pews within, with each row having two pews (and an extra kneeler for the front pew).

The pew backs are attractively adorned with miniature Romanesque-style balustrades,

each featuring the Ayala family’s coat of arms in the center.

On the wall to the left of the altar

is a trio of oil paintings on canvas by famed artist Atanacio “Tam” B. Austria, mounted onto arch-topped niches in the wall.

On the extreme left is “A Procession in Honor of Nuestra Señora de Paz y Buenviaje de Antipolo,” from 1970.

On the extreme right is “A Procession in Honor of Nuestra Señora del Santisimo Rosario de La Naval,” also from 1970.

And in between these two depictions of famous Philippine Marian processions is a most interesting Crucifixion scene, painted by Tam Austria in 1968.

This artwork was designed around an antique crucifix, reputedly from the collection of the artist Fernando Zobel (1924-1984), who died abroad and is not among the family members interred in this chapel.

To complement this crucifix, Austria painted the rest of the traditional “Calvario” scene, scaled to the size of the corpus, with the Dolorosa (Sorrowful Mother), Saint John, Mary Magdalene, and an additional unidentified Holy Woman all dressed in Filipiniana costume.

On the opposite wall adjacent to the altar’s right side

is a large mural in oil on canvas, painted by Fernando Zobel himself, of Christ seated in judgment, blessing with his right hand and holding the Book of Life in his left.

The words “Ego sum Resurrectio et Vita” – Latin for “I am the Resurrection and the Life” – encircle the figure of Christ. Four figures representing the evangelists are immediately next to him – on the left, a man for Matthew and a lion for Mark, and on the right, an eagle for John and an ox for Luke. This central panel is then flanked on each side by six apostles and two angels.

Immediately beneath this mural, which occupies the entire width of the right-side wall, are the wood-paneled niches for the ashes of deceased Ayala family members.

There are thirty-six niches in all, arranged in four rows of nine columns.

Only eight of the niches are currently occupied, three on the second row on the extreme left, and five on the second and third rows towards the middle.

The first of the three occupied niches on the left contains the remains of spouses Antonio Roxas Gargollo (5 April 1906 – 30 November 1982) and Maria de Mendezona Vda. de Roxas (20 May 1904 – 5 January 1985).

The title “Excmo.” is an abbreviation for “Excelentísimo” and roughly translates as “Excellency” or “The Honorable,” indicating perhaps that Don Antonio held an ambassadorial position or something equivalent. As his spouse, Doña Maria automatically received the equivalent feminine honorific, “Excma.,” short for “Excelentísima.”

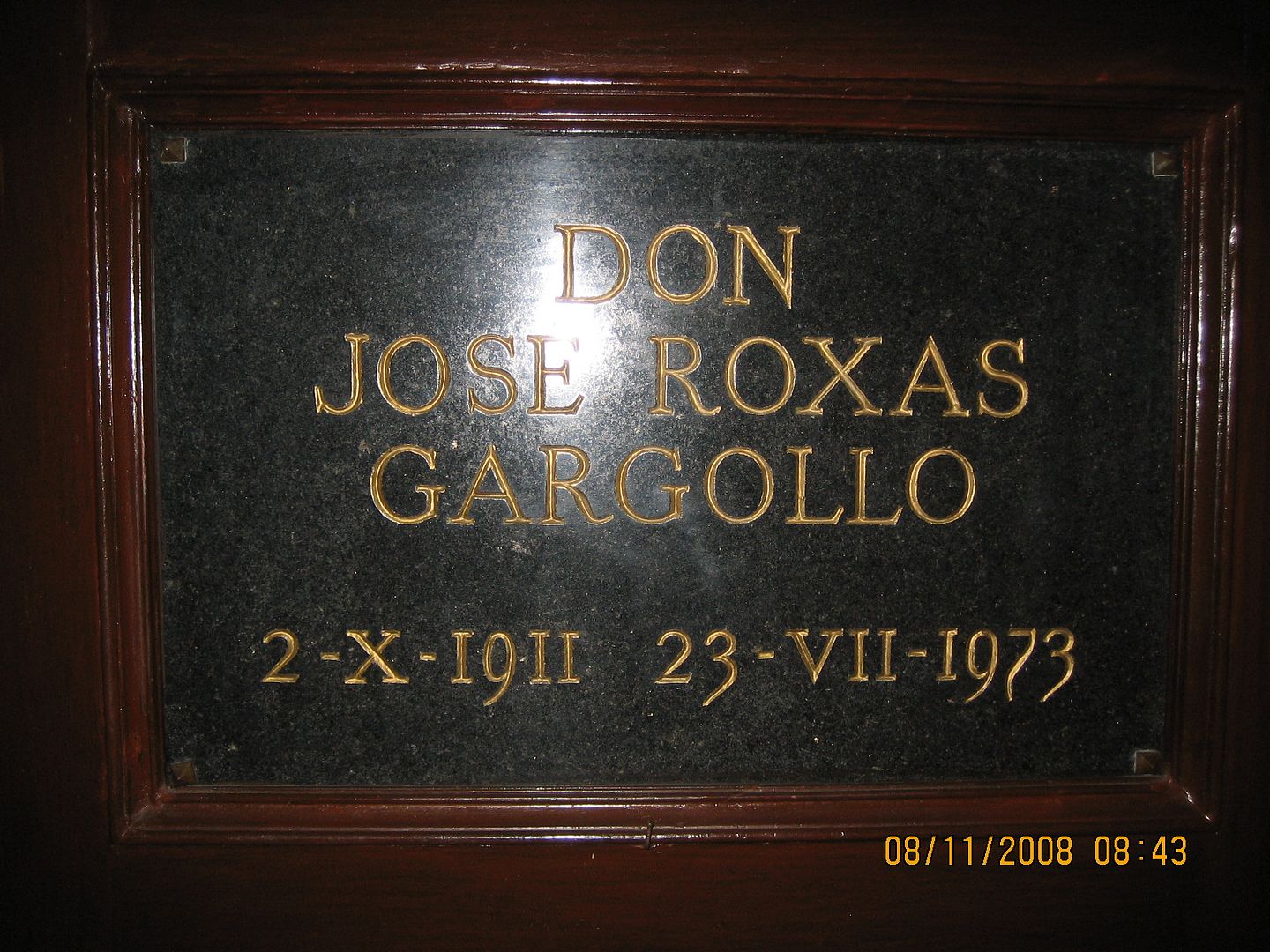

Next to them lie the remains of Don Jose Roxas Gargollo (2 October 1911 – 23 July 1973), presumably a brother of Don Antonio.

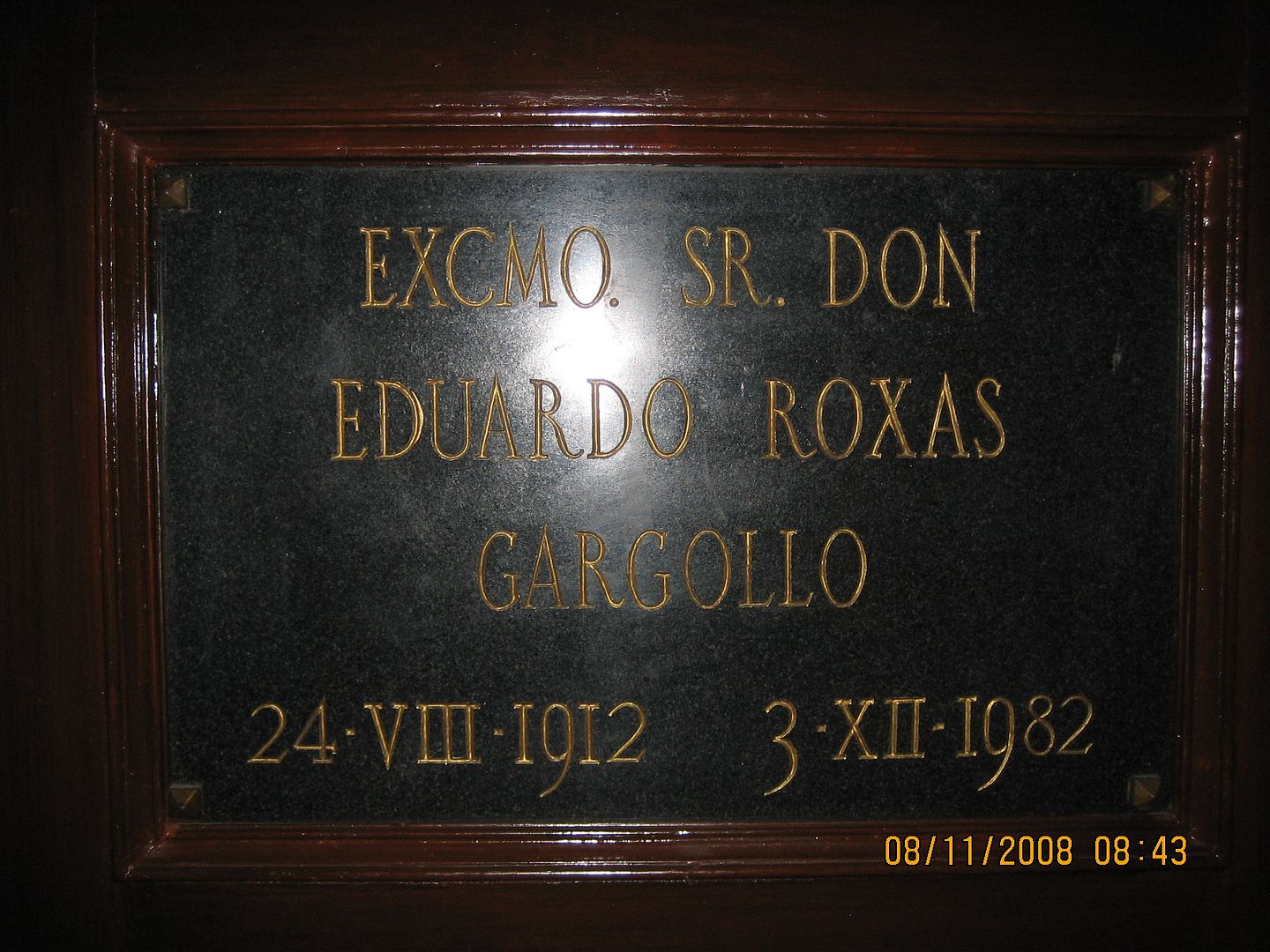

And next to him is His Excellency Don Eduardo Roxas Gargollo (24 August 1912 – 3 December 1982), presumably yet another sibiling of Don Antonio and Don Jose.

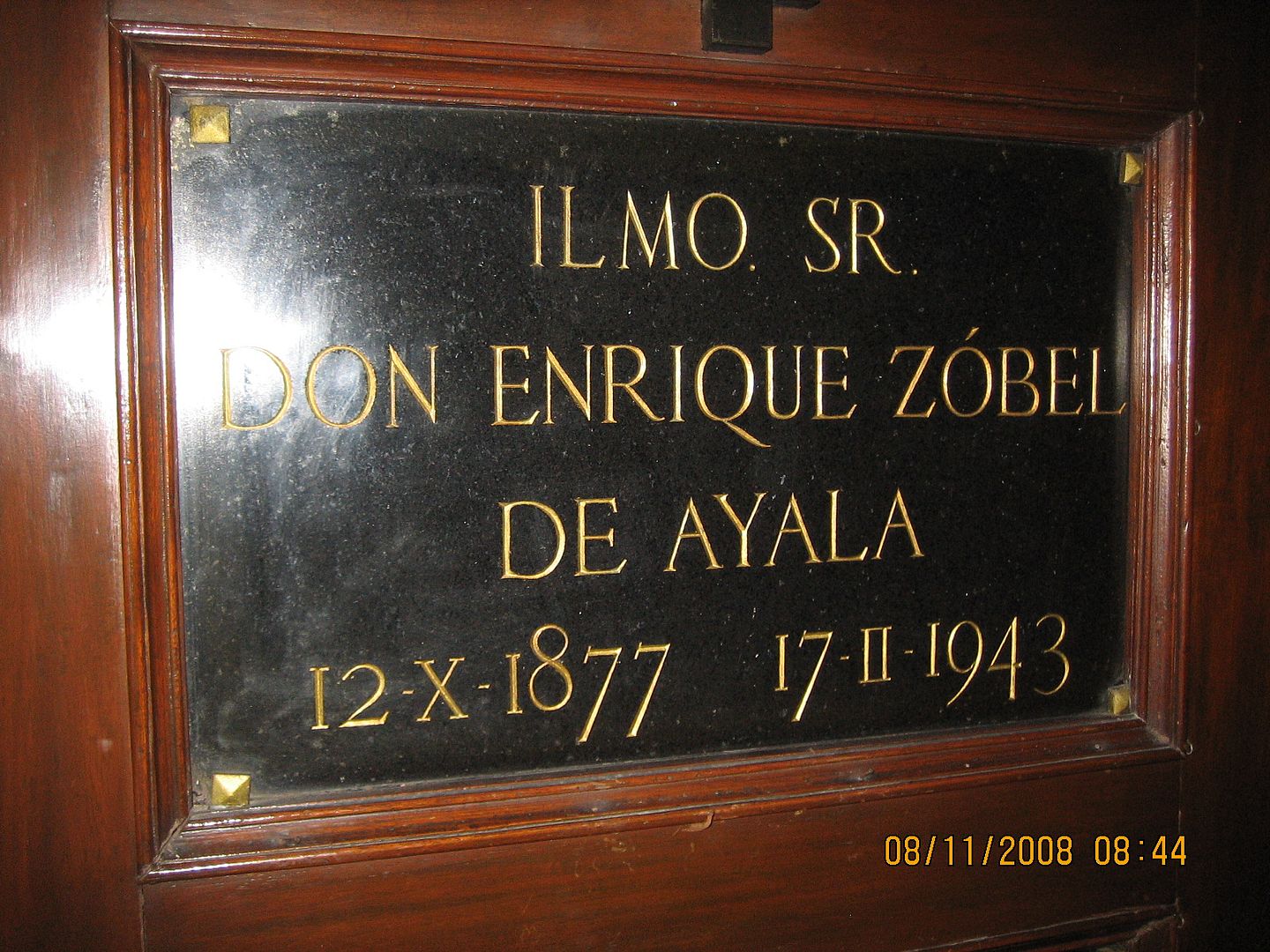

Two slots to the right of Don Eduardo lie the remains of Don Enrique Zóbel de Ayala (12 October 1877 – 17 February 1943).

His title “Ilmo.” is an abbreviation for “Ilustrísimo,” roughly equivalent in English to “His Lordship,” “Lord,” or simply . . . “Mister.”

Directly beneath Don Enrique is his wife Doña Fermina Montojo Torrontegui de Zóbel de Ayala (7 July 1881 – 24 September 1966).

Doña Fermina was actually Don Enrique’s second wife, as he first married his cousin Doña Consuelo Roxas de Ayala in 1901, who died at the early age of thirty-three due to a cholera epidemic, leaving three young children. (On the other hand, Doña Fermina eventually bore Don Enrique five children, one of whom was Fernando Zobel, the artist of the mural overhead.)

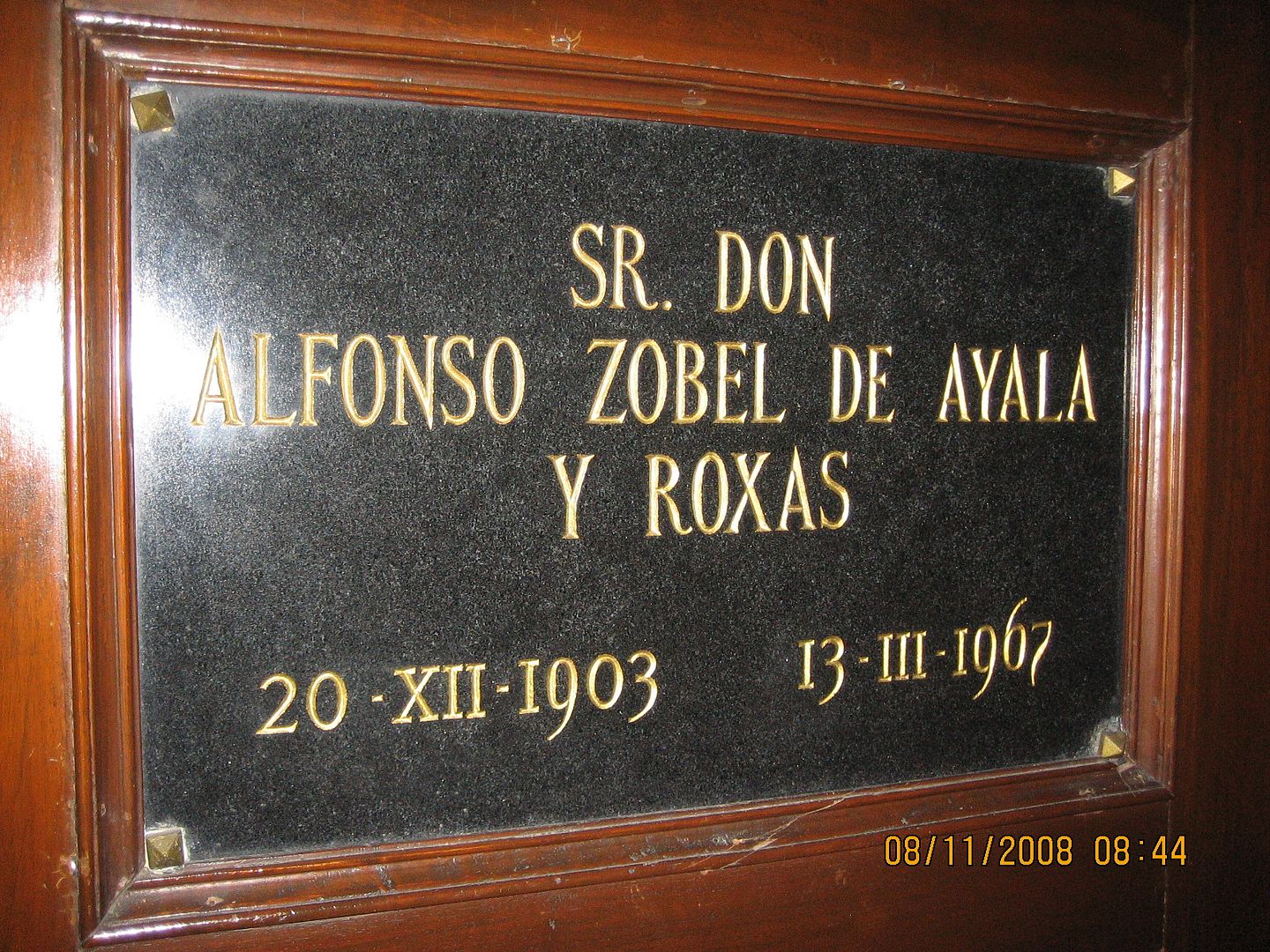

One of the three orphaned offspring of Doña Consuelo is interred to the right of his father Don Enrique: Don Alfonso Zóbel de Ayala y Roxas (20 December 1903 – 13 March 1967).

Directly beneath Don Alfonso is his wife Doña Carmen Pfitz Herrero de Zóbel de Ayala (22 March 1909 – 10 December 1999).

Don Alfonso and Doña Carmen are the parents of Don Jaime Zóbel de Ayala (born 1934), currently Chairman Emeritus of the Ayala Corporation, from which he retired as Chairman in 1995.

Immediately to the right of Doña Carmen lie the remains of spouses Colonel Joseph R. McMicking (23 March 1908 – 5 October 1990) and Doña Mercedes Zóbel McMicking (5 May 1907 – 3 December 2005).

Doña Mercedes was the younger full sister of Don Alfonso, who married Colonel McMicking in 1931. McMicking was instrumental in running the family firm in the post-war years alongside Don Alfonso, especially in regard to the development of its Makati landholdings to become the premier residential and commercial district in the Philippines.

(The remaining full sibling of Alfonso and Mercedes was Don Jacobo Zóbel de Ayala, whose only son was Enrique Olgado Zóbel [1927-2004], who led the family corporation in the post-McMicking years. Neither Jacobo nor Enrique are buried in this chapel.)

We take a final look at the eight brass-faced niches, helped along by a friendly (and wealthy-looking) orb.

The rear wall of the chapel has a lone balustered window that communicates with the confessional room next door. I photographed it with and then without flash.

The rest of the rear side of this squarish chapel consists of the arched doorway that we entered at the beginning, now seen here from the inside

from which we can also view the left-side nave of the main church.

As we leave the Ayala Chapel, we realize that even if, as they say, you can’t take it with you, it’s only the other half that can afford to be surrounded by art and antiques even in the afterlife.

I really should make arrangements to be buried with my favorite aparador.

Originally published on 9 November 2008. All text and photos copyright ©2008 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Original comments:

zambaleno wrote on Nov 12, '08

Forget being buried "with" your aparado. Just make arrangements to be buried IN your aparador! LOL

|

rally65 wrote on Nov 12, '08

zambaleno said

Forget being buried "with" your aparado. Just make arrangements to be buried IN your aparador! LOL

I'll have to have the shelves taken out first then. Ha ha ha.

|

johnada wrote on Nov 24, '08

leo,

is the altar attached to the wall or free-standing? |

rally65 wrote on Nov 24, '08

johnada said

leo,is the altar attached to the wall or free-standing?

The altar table is free-standing, as this chapel was built post-Vatican II, perhaps in the early 1970's.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment