(Fifth in the “Praying Twice” Series)

“Cantat Bis Orat.” [“To sing is to pray twice.”] – Saint Augustine

As I start to write this, it is Thursday May the 17th, Ascension Day, and ironically a public holiday here in predominantly Muslim Indonesia where I just happen to be. I got back from High Mass at 11:00 this morning at the Saint Peter Canisius International Roman Catholic Parish Church (actually at the Gereja Santa Theresia [Saint Therese Church] in Menteng, a few blocks from where I’m staying in the embassy district) where I always go on Saturday afternoons.

The service was great, the homily by the Indonesian Jesuit celebrant stimulating as always, and the full-bodied (and full-blooded) singing by the predominantly expatriate Filipino choir inspiring, as might be expected.

Except that none of the music seemed to have been written specifically for the Feast of the Ascension of Our Lord. So obsessive-compulsive me felt impelled to rummage through my family’s music library to see what might be available.

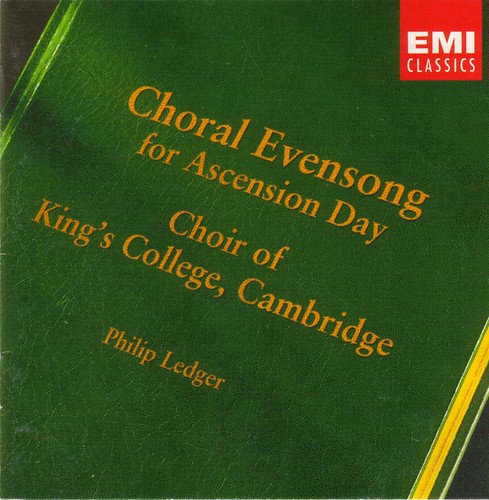

I tell you, being obsessive-compulsive always pays off. I had previously written about The Choir of King’s College,

And in that article, I had already included a sample track from this album, a setting of Psalm 24, “The Earth is the Lord’s” by Sir Joseph Barnby (1838-1896).

Well, it seems like as good a day as any (in fact, the best day of all) to listen to this entire album again. This is essentially a recording of an Anglican Church service, which has a substantial degree of similarity in form to a Roman Catholic Mass, in that it also has hymns and readings from scripture. The term “choral evensong” signals us to the fact that with the exception of a few prayers and readings, the entire service is sung, in this case by the outstanding King’s College Choir. And for this Feast Day, all the texts have been selected to emphasize the glory and hope that we ought to identify with the Ascension of the Lord.

The service opens with the Introit, “Alleluia, Ascendit Deus,” in a brief setting by William Byrd (1543-1623) to the original Latin text.

Alleluia, Ascendit Deus

Et Dominus in voce tubae. Alleluia.

Et Dominus in voce tubae. Alleluia.

[Alleluia: God is gone up with a merry noise,

And the Lord with the sound of the trumpet. Alleluia.]

After a few opening prayers and the Psalm 24 setting by Joseph Barnby that we had listened to in the earlier article, the congregation joins the choir in the hymn “The head that once was crowned with thorns” with music by Jeremiah Clarke and words by Thomas Kelly.

The head that once was crowned with thorns

is crowned with glory now.

A royal diadem adorns

the mighty Victor’s brow.

A few more readings and responses later comes a popular choral showcase from Jacobean England, a setting of Psalm 47, “O Clap Your Hands” by Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625). This is, a bit unusually, in eight parts, that is, in the usual soprano, alto, tenor, and bass, but for divided choir.

O clap your hands together, all ye people:

O sing unto God with the voice of melody.

For the Lord is high, and to be feared:

He is the great King of all the earth.

This is followed immediately by a Latin motet “Ascendit Deus,” by Peter Philips (1561-1628), a Gibbons contemporary who chose to live in exile on the Continent than be subject to persecution in his native

Ascendit Deus in jubilatione,

Et Dominus in voce tubae.

Alleluia.

Dominus in coelo paravit sedem suam.

Alleluia.

[God is gone up with a merry noise:

And the Lord with the sound of the trumpet.

Alleluia.

The Lord hath prepared his seat in heaven.

Alleluia.]

And after a few more closing prayers and a final blessing, the service winds down with a congregational hymn, “The Lord Ascendeth Up On High,” with original music attributed to Martin Luther and adapted and harmonized by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). The English text is by A. T. Russell (1806-1874).

The Lord ascendeth up on high,

Loud anthems round him swelling;

The Lord hath triumphed gloriously,

In power and might excelling:

Hell and the grave are captive led;

Lo, he returns, our glorious Head,

To his eternal dwelling.

I know what some of you are thinking – this is all so square and “high-church” establishment-sounding. And it’s not even Roman Catholic. Even if the Peter Philips “Ascendit Deus” was written by a loyal Roman Catholic Englishman.

Not to worry, we have something else. Two Christmases ago, in December 2005, I was in one of those “anticipated” Simbang Gabi (Nine-Day Dawn Masses), which, if that sounds confusing to you, you’re not the only one – they’re actually celebrated the night before, usually at 6:00 pm of the previous day. This was at the Santuario de

It was a normal uneventful Advent Novena Mass, except that during the Communion, the solitary music provider, a young lady with an acoustic guitar, sang what struck me as a most interesting, most refreshing church song, something that I had not heard before.

Like some new song heard once on the radio, I promptly forget about it. Then several months later, while on an extended business trip to

What made it even grander was that the all-male Choir of Melbourne Cathedral was on hand, and although they could never hope to be at par with the Choir of King’s College Cambridge, their presence ensured that the service was sufficiently musical to keep even jaded foreigners like me perked up.

And guess what, for the Communion Hymn, that song that I had heard in

Christ, be our light!

Shine in our hearts.

Shine through the darkness.

Christ, be our light!

Shine in your church

Gathered today.

The refrain had a beautiful descant part (top-line harmonic counterpoint) sung by the choir’s boy sopranos. Obviously their Choirmaster liked the piece so much that they even reprised it and used it also as the Recessional Hymn on that Ascension Day.

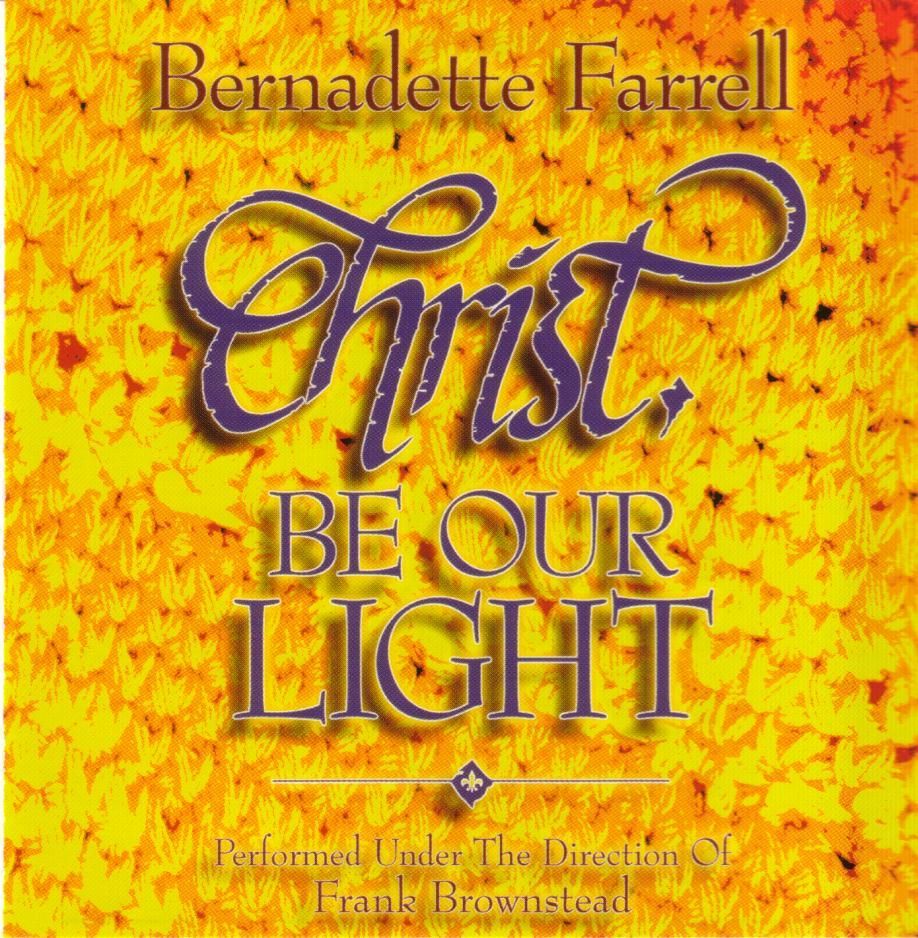

Subsequent digging and research allowed me to identify the piece as “Christ, Be Our Light” and to find a decent recording.

This piece was composed in 1993 by Bernadette Farrell, a prolific British Roman Catholic hymnwriter, born in 1957.

“This song was originally written for the dedication of a church, St. Gabriel’s in Upper Holloway. The assembly was to be in semi-darkness, with only the Paschal candle burning. The light would spread around the church during the song as individual candles were lit. Something was needed which could be sung without words or rehearsal.

“The text is appropriate for many different occasions. The refrain is for everyone, while the verses might be sung by a soloist or group. Sing the refrain strongly, emphasizing the first beat of the measure. And, as always, only introduce the descant once the melody is swinging.”

In fact, I thought that this hymn was quite fitting not only that Advent evening when I first heard it, but also that cold Ascension Sunday morning when I heard it (and sung along to it) again.

Listen to it, sing along, let the melody swing, and make a merry noise!