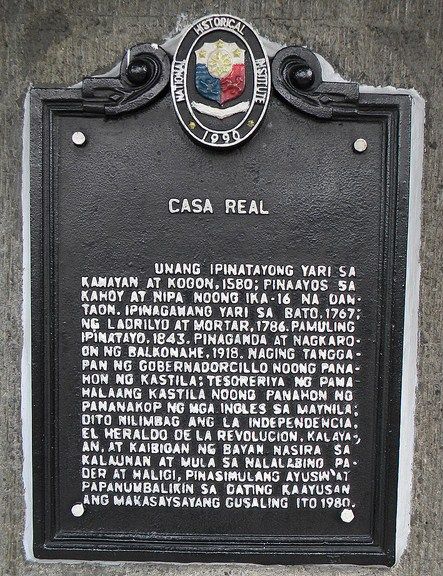

A National Historical Institute marker by the main entrance provides the basic information that we need.

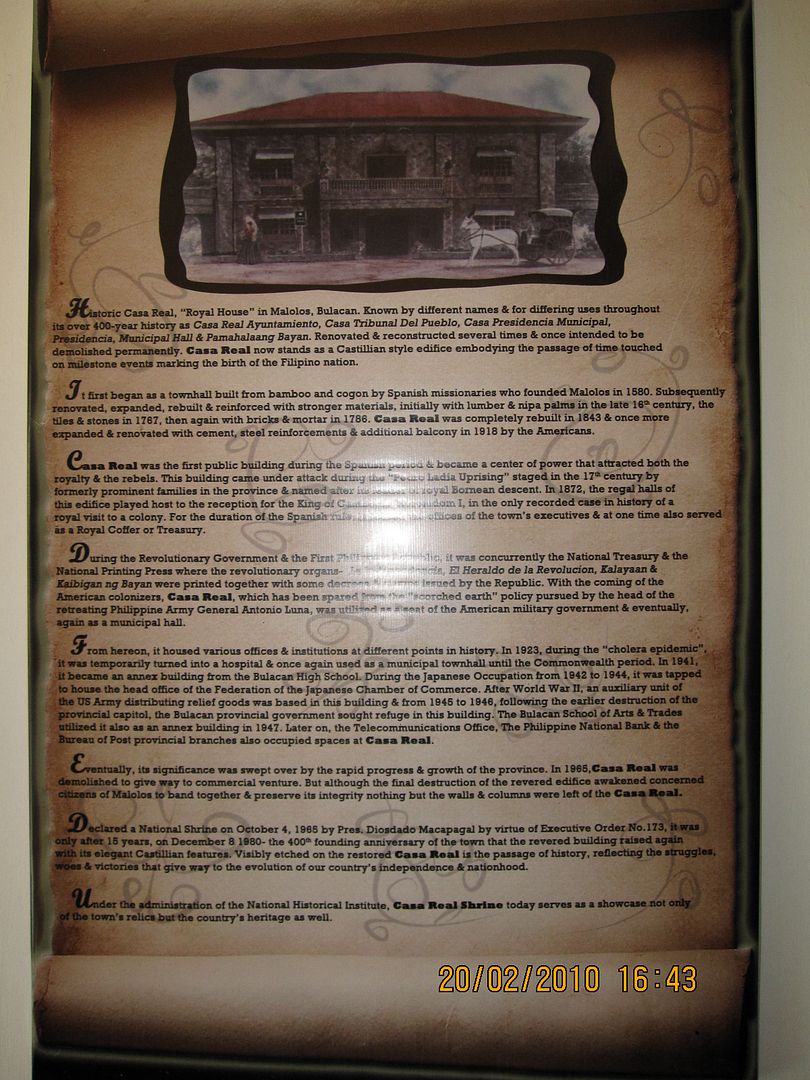

The original Casa Real of Malolos, which was the municipal hall and where the gobernadorcillo or town mayor held office, was originally erected in 1580 of light materials such as bamboo and cogon grass. It was rebuilt in stone in 1767, then of brick in 1786. It was further upgraded and likely enlarged in 1843, perhaps almost contemporary with the Casa Tribunal. When Malolos was split into the three towns of Malolos, Barasoain, and Santa Isabel in 1859, the Casa Tribunal became the town hall of the new “smaller” Malolos, and the Casa Real became the town hall of Barasoain, since it stood across the river in Barasoain territory.

At the start of the American colonial period, the three towns were reconstituted as Malolos once again, and the new “larger” Malolos was made the provincial capital. The Casa Real, which was bigger than the Casa Tribunal, became the municipal hall for the new capital town. (The colonial government built a separate large and impressive provincial capitol building across town.)

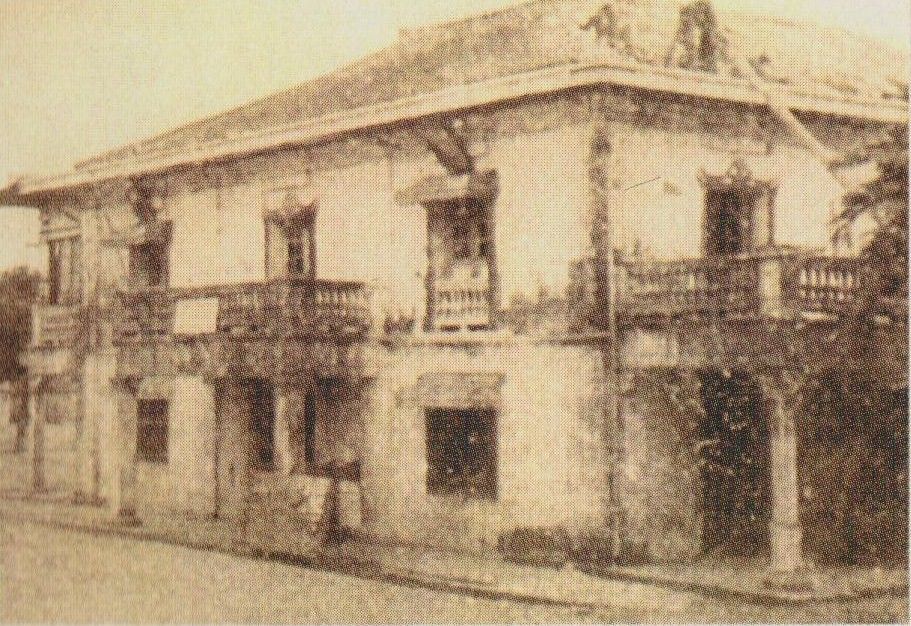

In 1918, the Casa Real was renovated and further enlarged with the addition of balconies. This archival photo from the Dr. Nicanor Tiongson Collection and published in his book “The Women of Malolos” shows those balconies and must have therefore been taken in or after 1918.

In 1940, the colonial government built a new “Municipio” for Malolos, diagonally across the bridge from the Casa Real and directly across the parish church, where the town’s previous “daungan” or main river pier must have been. (With the shift in means of transportation from river to road, a repurposing of the site must have been a fair call.)

After the municipal government moved out, it was occupied by various tenants in turn: the Bulacan High School in 1941, the Japanese Chamber of Commerce during the Occupation from 1942 to 1944, an auxiliary unit of the US Army after Liberation in 1945, the Bulacan provincial government until 1946, the Trade School in 1947, and the Telecommunications Office, the Philippine National Bank, and the Post Office in subsequent years.In 1965, most of the structure was demolished to set up a gas station on a portion of the property. By the 1970’s, when I was a schoolboy in town, I passed it every day and saw it as a maze of fallen stone columns and beams with overgrown weeds.

But miraculously, the spirit of heritage preservation made itself felt in Malolos then. A group of concerned citizens went to court and successfully sued to demand the structure’s restoration and reversion to non-commercial use. As a result, in 1980 the Casa Real was rebuilt from the remaining structural members, aided by archival photos as references, and with funding from the office of then First Lady Imelda Marcos and the Bulacan Historical Society.

Now called the Casa Real Shrine, it is managed by the National Historical Institute

and is open daily except Mondays.

For the past thirty years, the Casa Real has been Malolos’ usual venue for historical and artistic activities and events, including, in some years, exhibits of religious images to coincide with special feast days, for example, the feast of town’s patroness, the Immaculate Conception, on December 8th, and the feast of the Santo Niño on the last Sunday of January. Soon after its restoration in the early 1980’s, a major Santo Niño religious exhibit was held there, which was the first and last time that I set foot inside the structure.

Until earlier this year, in February 2010, when I was asked to accompany a group of out-of-towners around, and saw this as a great opportunity to visit again after such a long time.We enter the wrought-iron main gate, not originally there in the structure’s pre-war incarnation, but probably a good idea now to guard against vandals and other nuisances of modern living. From there one enters the main doors that lead directly to the entrance hall.

In the entrance hall is a poster with historical information on the Casa Real, as I have already summarized above,

and beyond the archway

is an old printing press,

alluding to the building’s use as the communications center of the Malolos Republic of 1898, a.k.a. the Philippine revolutionary government headed by Emilio Aguinaldo, where were printed and published their newspapers, bulletins, manifestos, and communiqués.

The entrance hall allows access to rooms on the left and on the right. The right-hand wing of the ground floor holds the Casa Real’s religious artifacts collection, including a smaller-than-life-sized processional image of Saint Raphael the Archangel,

an ornately carved tabletop urna with a small tableau depicting Roman soldiers, apparently missing its essential Christ figure,

another ornately carved urna, possibly a reproduction, empty and on the floor,

and an oil painting of a home altar, which is probably modern but still on-theme.

The room also houses the Casa Real’s Filipino furniture collection, including several sets of round tables and chairs.

There was a rectangular dining table and chairs, inscribed “1973” and bone-inlaid in the ubiquitous Bulacan style,

as well as two lansenas or sideboard cabinets, one tall and marble-topped,

the other wide and decorated with carvings,

both at the larger end of the spectrum of lansenas, typifying those of the second half of the 19th century.

There were several aparadors or wardrobes, including a “tambol” or wood-panel-fronted one with an arched top,

a large neoclassical one with balustraded crown,

and a deceptively simple-looking one that I could have sworn I first saw unrestored some years ago in an antique dealership, that actually came in three separate parts – top, middle, and bottom –

and originally even had a rolltop-type cover for the mirror (presumably to conform with the superstitious belief in some quarters that mirrors should not be uncovered next to sleeping humans).

There was even a very desirable matched pair of oversized single-door aparadors

with the works – finials, balustraded crowns, fluted columns, and discus feet, among other touches.

A smaller room in this section was set up to simulate a 19th century bedroom, therefore it was furnished with a canopied bed,

a flat-topped tambol aparador,

and a glazed aparador, which showed off a selection of period dresses well.

Towards the far end of this quarter of the Casa Real was the kitchen area, not really authentic as the original building’s functions likely excluded such domestic activities. Nonetheless, on display were a reconstruction of a traditional open-hearth stove,

and a selection of traditional kitchen utensils, set on a reconstructed “banggera” or open-windowed washing and drying area.

Back in the main exhibit hall, we espy a foldable and portable lounging chair,

and a long and wide bench-cum-daybed.

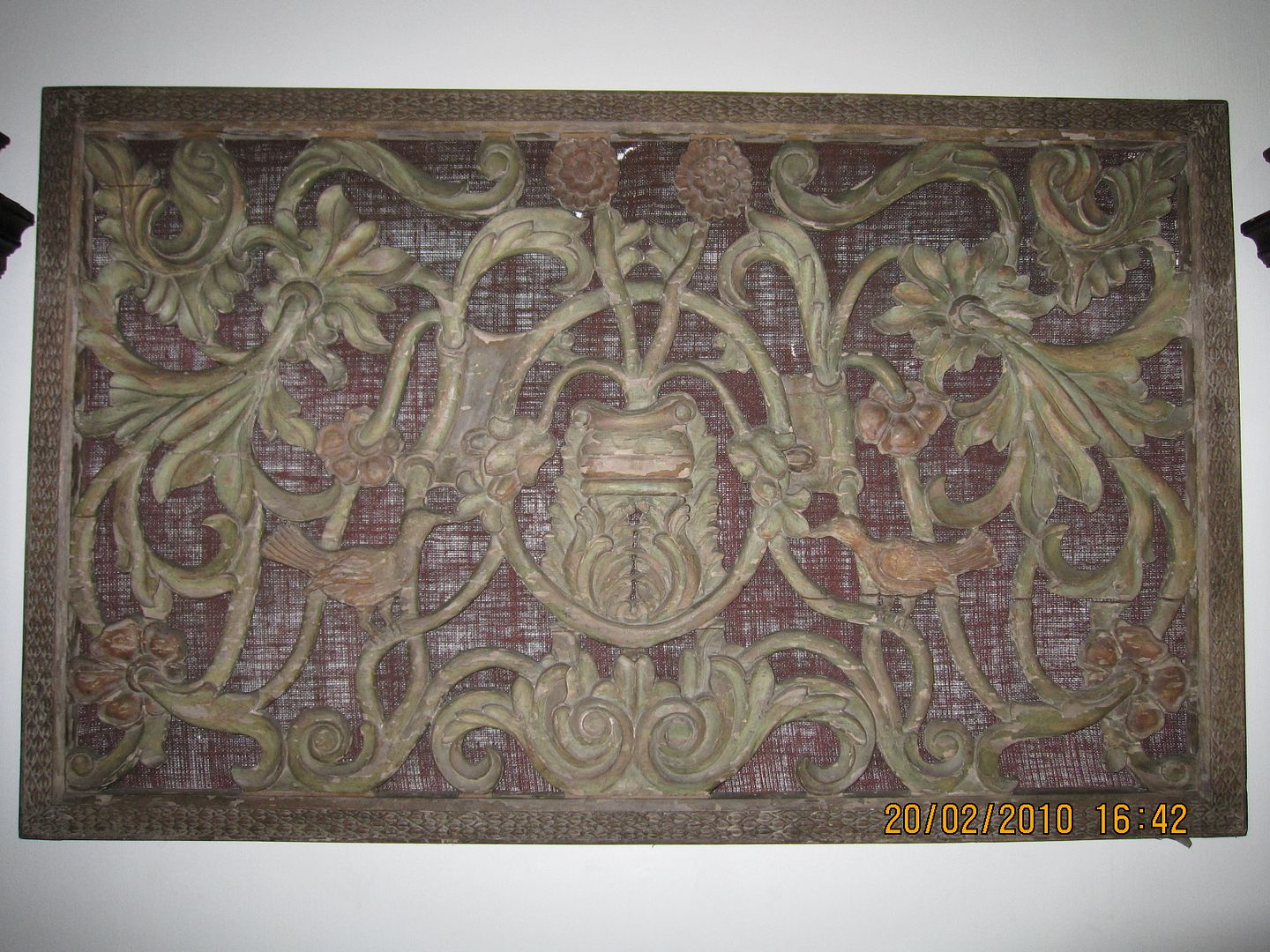

Before we leave this hall, we note a few more artifacts mounted on the walls. There are a couple of antique curtain valances for doorways,

no longer with their matching curtains,

and an ornate foliate design of indeterminate material.

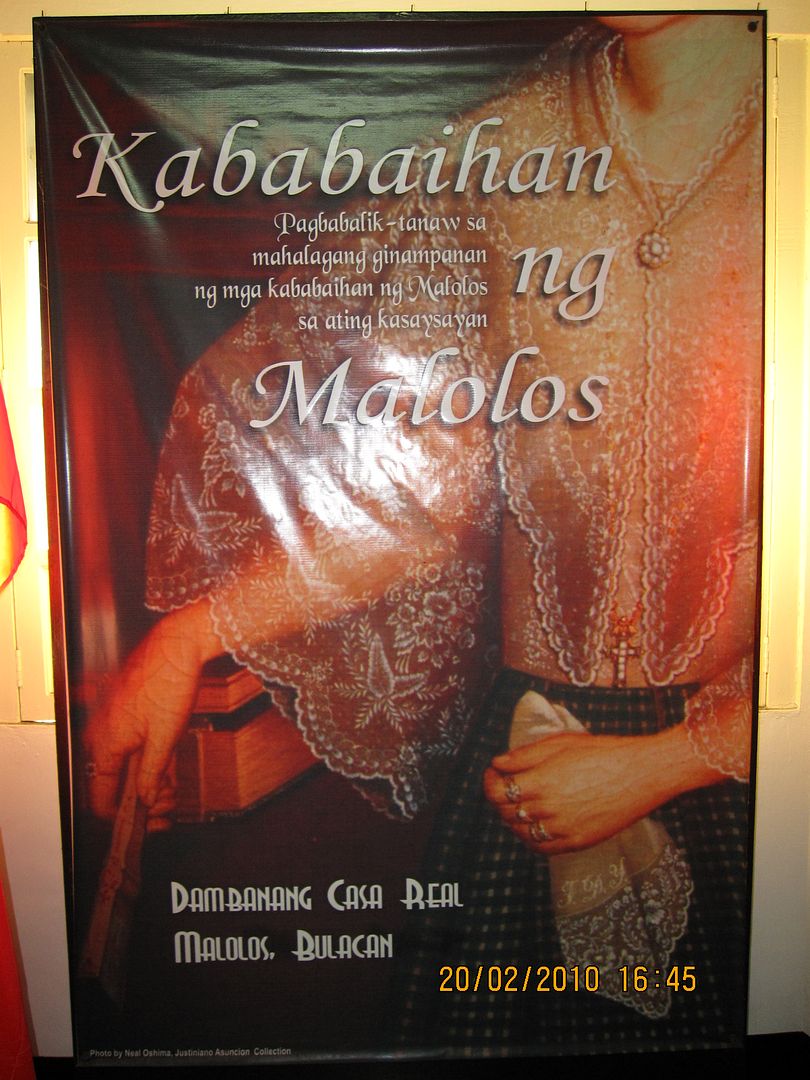

Going back to the outside and crossing over to the room on the left side of the entrance hall, we find that the Casa Real’s other permanent ground-floor exhibit is a memorial to the venerable Women of Malolos,

some of whose ancestral houses we have already visited and written about over the past few years.

The exhibit was put up by the Women of Malolos Foundation,

an organization originally composed of descendants of the original women, but now increasingly broad-based and involved in various of Malolos and Bulacan heritage issues.

Most of the materials on exhibit here, however, were reproductions of archival photographs also found in Dr. Nick Tiongson’s iconic and same-titled work on the Women of Malolos, so I decided not to photograph them any longer. There was also a selection of personal effects originally owned by the women, such as dresses and fans, but they weren’t all that photogenic, so I passed on them as well. Those keen on such things will be better off seeing them face-to-face by visiting the Casa Real in person.In the end, all I got to photograph in this particular exhibit was a low-relief wooden group portrait of the Women of Malolos conjecturally together with their most famous correspondent, Dr. Jose Rizal, in the second row center,

and, definitely less creepily, a very nicely-framed print of a Rizal portrait, solo this time.

Back outside, we go to the far end of the entrance hall, and ascend the staircase,

and emerge on the second floor landing, now in granite versus the presumed wooden original.

The balustrade enclosing the stairwell

also leads to a doorway

which admits into a very large room,

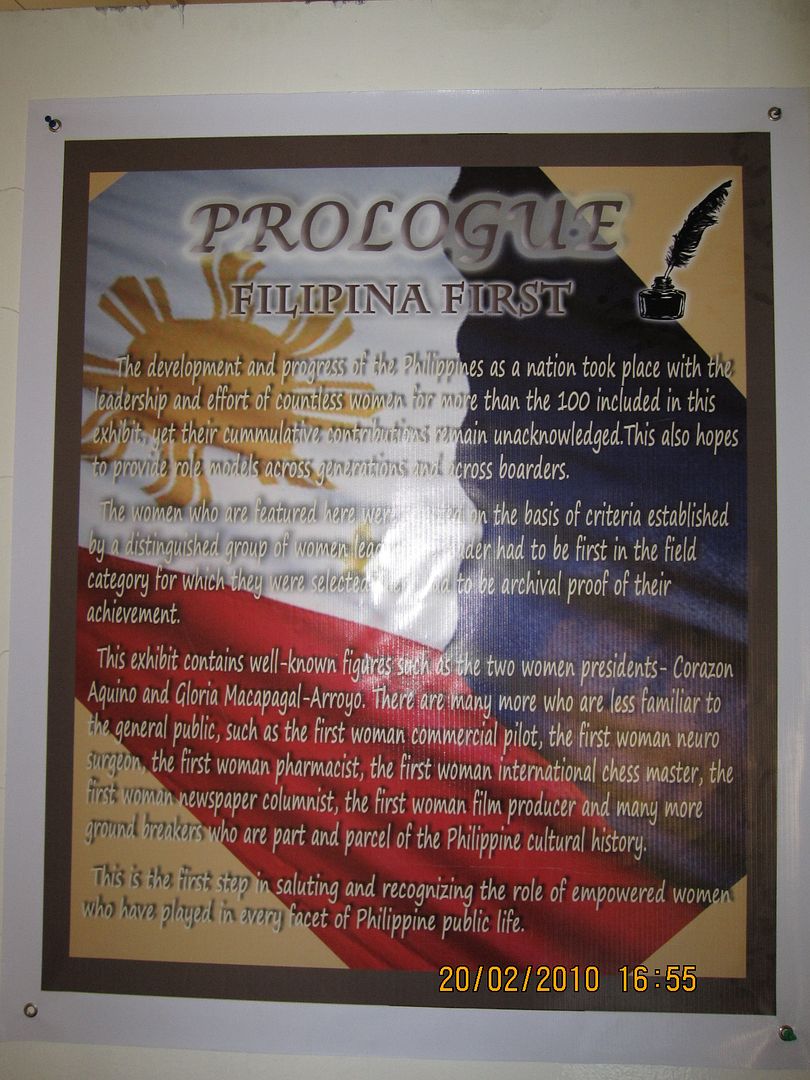

which is the Casa Real’s multipurpose hall, where less-permanent exhibits are staged,

which at this time was something called “Filipina First,”

a logical complement to the “Women of Malolos” on the ground floor.

On one wall in a corner was what appeared to be a permanent fixture,

an expository mural on key people and events in the revolutionary history of the province of Bulacan.

The ceiling here was in the 1970’s Philippine neo-antique coffered-ceiling style,

which was not made more believable by nouveau-riche six-armed chandeliers,

nor by utilitarian-looking steel-bladed ceiling fans.

This hall was large enough to host social activities of the dinner-dance variety, as it had the practical though still inauthentic wooden parquet floor underfoot.

In the end, what I found most interesting were the wide rows of glazed and wrought-iron-grilled sliding windows

on three sides of the hall,

and the large double doors that they flank,

that, if unlocked, would allow passage

to the large balconies on the north, west, and south sides,

originally erected, we might recall now, in 1918.

And so ended my latest visit to the thirty-year-old resurrected Casa Real shrine.

Which, even if it isn’t all that period-authentic to say the least,

is a tangible sign that Malolos is still better off in the heritage department than many other urbanized provincial towns and cities around,

even if amateur photographers like me have to compete with jeepneys, tricycles, and autocalesas, just to get a clean shot.

Originally published on 11 December 2010. All text and photos (except as otherwise attributed) copyright ©2010 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

No comments:

Post a Comment