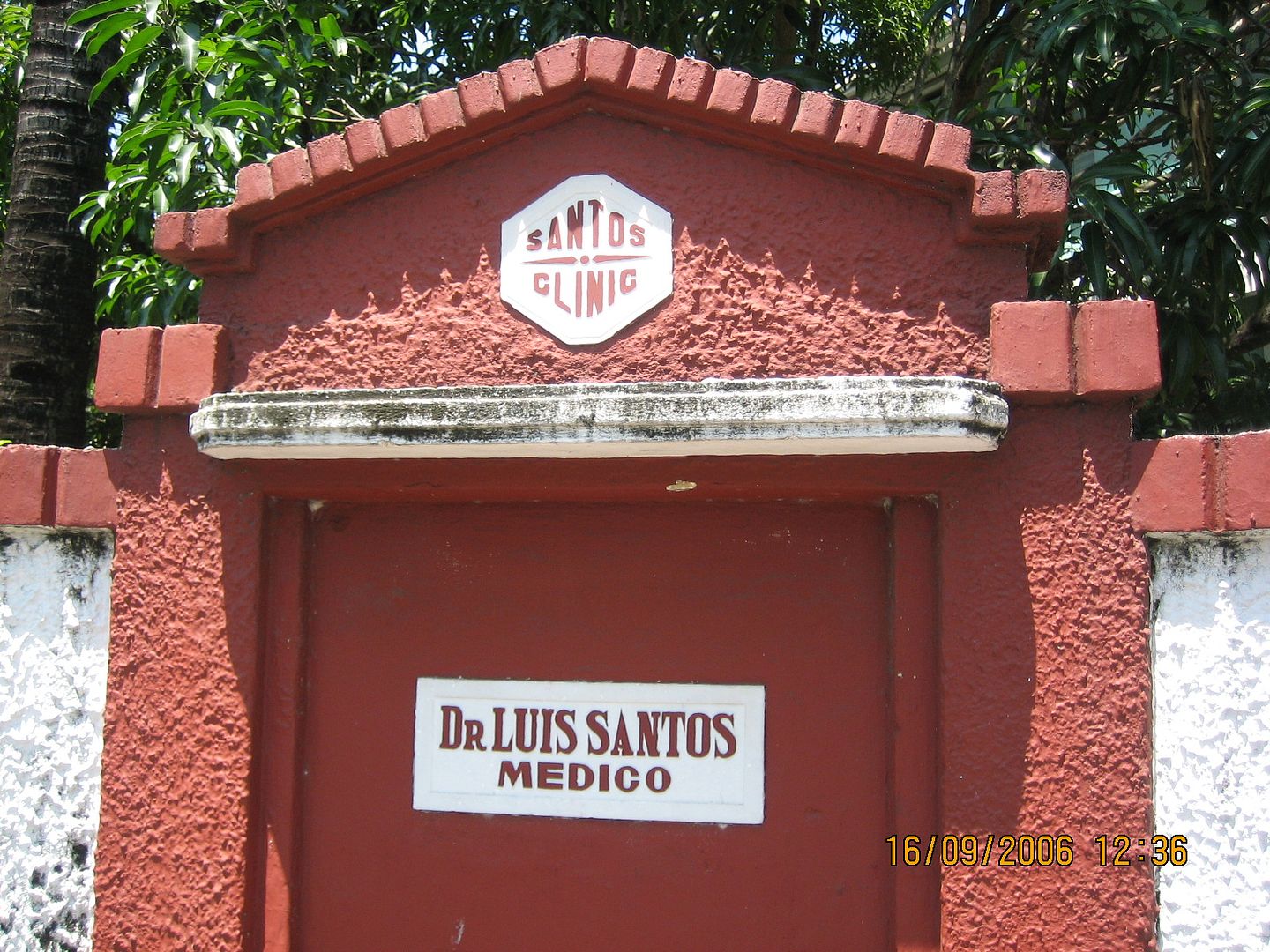

This was built in 1933 by the second of Paulino’s and Alberta’s nine children, Luis, born in 1893, and an eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist of considerable nationwide renown for most of the 20th century until his death in 1982. A prominent sign inscribed into the stone of the fence right beside the main gate clearly identifies the master of the house and his profession.

And the opposite panel on the other side of the gate provides unequivocal confirmation of the date of the house’s construction.

Right off, let me disclose that I had decided a long time ago, even before this visit, that this was the most beautiful and the most gracious of all the Malolos ancestral houses, which is not exactly a mediocre crowd. And with the demolition in 2009 of the stately Lino Reyes House just diagonally behind this house, this singular distinction has only become more firmly established in my mind.

Therefore my only objective with this Akyat-Bahay visit was to confirm what I already knew. And to capitalize on the great privilege on that day in September 2006 of having for my tour guide none other than Dr. Luis' son and heir, the equally prominent eye specialist, Dr. Sabino "Benny" Santos, Sr. Having pre-arranged the visit through Dr. Benny's son, Dr. Sabino Junior (yet another eye specialist, now in the third generation), I walk down the road towards the house,

Therefore my only objective with this Akyat-Bahay visit was to confirm what I already knew. And to capitalize on the great privilege on that day in September 2006 of having for my tour guide none other than Dr. Luis' son and heir, the equally prominent eye specialist, Dr. Sabino "Benny" Santos, Sr. Having pre-arranged the visit through Dr. Benny's son, Dr. Sabino Junior (yet another eye specialist, now in the third generation), I walk down the road towards the house,

enter the elaborate wrought-iron main gate on the left-hand side of the frontage,

and walk up the expansive semicircular driveway,

that sets the house generously away from the street.

This set-back allows for a spacious front garden circumscribed by the driveway and the fence fronting the street that features a most inspired monumental fountain featuring a pair of lovely nymphs.

Walking further up the driveway allowed me to get a close-up view of the structure

and take a good look at the façade's intricate Art Deco styling, whose order and symmetry are more evident when viewed full-frontally,

as well as vertically,

and even as I keep walking down the driveway

to view the right side of the façade.

The main body of the house is flanked on the right by a two-bay parking shed,

and on the left by a double-doored garage.

To the left of the house and accessible both from the street in front and from the house’s driveway via this doorway

is a more recent post-war building that was Dr. Luis’ and subsequently Dr. Benny’s clinic, after its first location, which regular readers will recall was the ground floor of Dr. Luis’ parents’ house diagonally across the street from here.

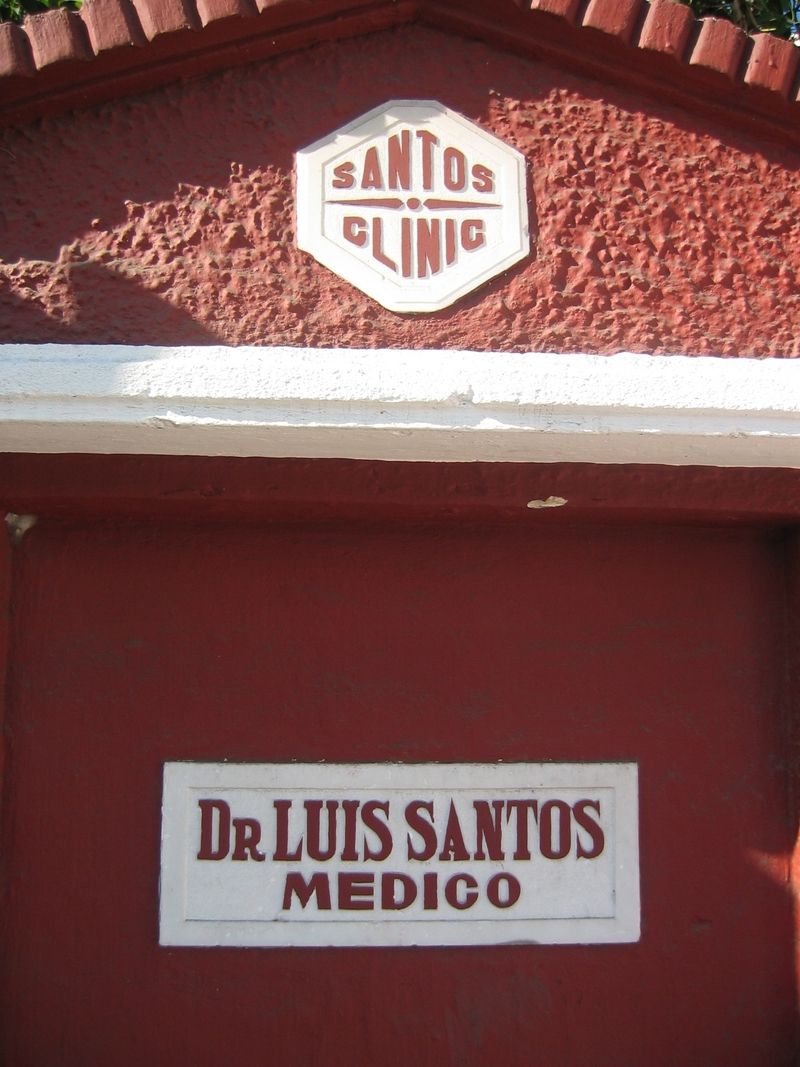

But in fact before this purpose-built building and after the ground floor of the family home, Dr. Luis' clinic was the ground floor of his own house, from the time it was completed in 1933. The sign by the gate clearly says "Santos Clinic' within the octagonal medallion above the good doctor's name.

But in fact before this purpose-built building and after the ground floor of the family home, Dr. Luis' clinic was the ground floor of his own house, from the time it was completed in 1933. The sign by the gate clearly says "Santos Clinic' within the octagonal medallion above the good doctor's name.

This will explain why the house features two main doors, adding to the overall symmetry of its façade. The door on the left leads directly to the clinic, and the door on the right to the private residence.

I ascend the entrance balcony, and look up to appreciate the original Art Deco light fixtures.

Taking the door on the left, which looks like this from the inside,

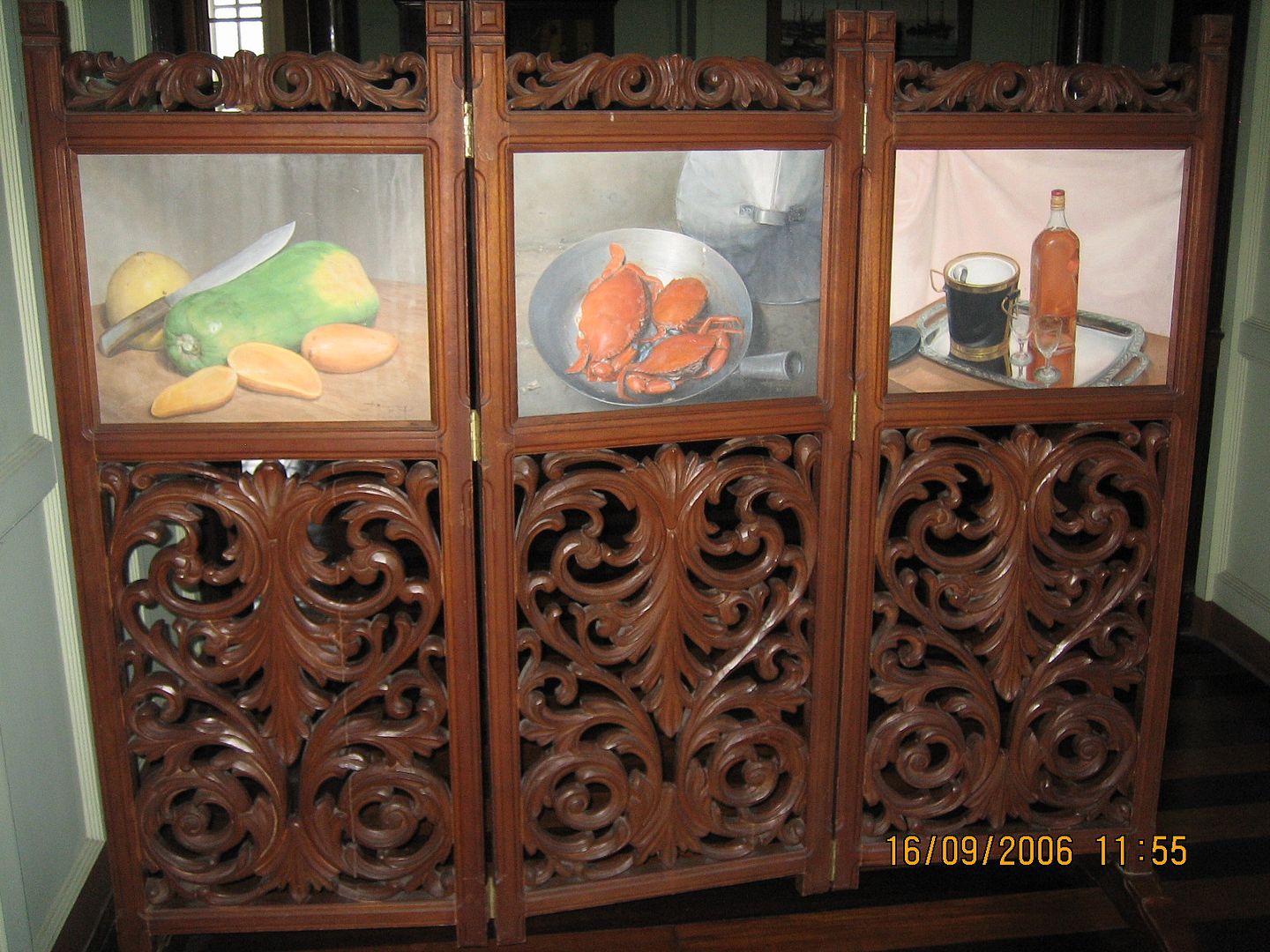

brings one to a small foyer, where stands this carved wooden screen with still-life-painted panels.

Directly to the left from this foyer is a pair of white doors with frosted glass panels.

This leads to a spacious semi-octagonal room with white walls, large glazed windows, and a tall ceiling.

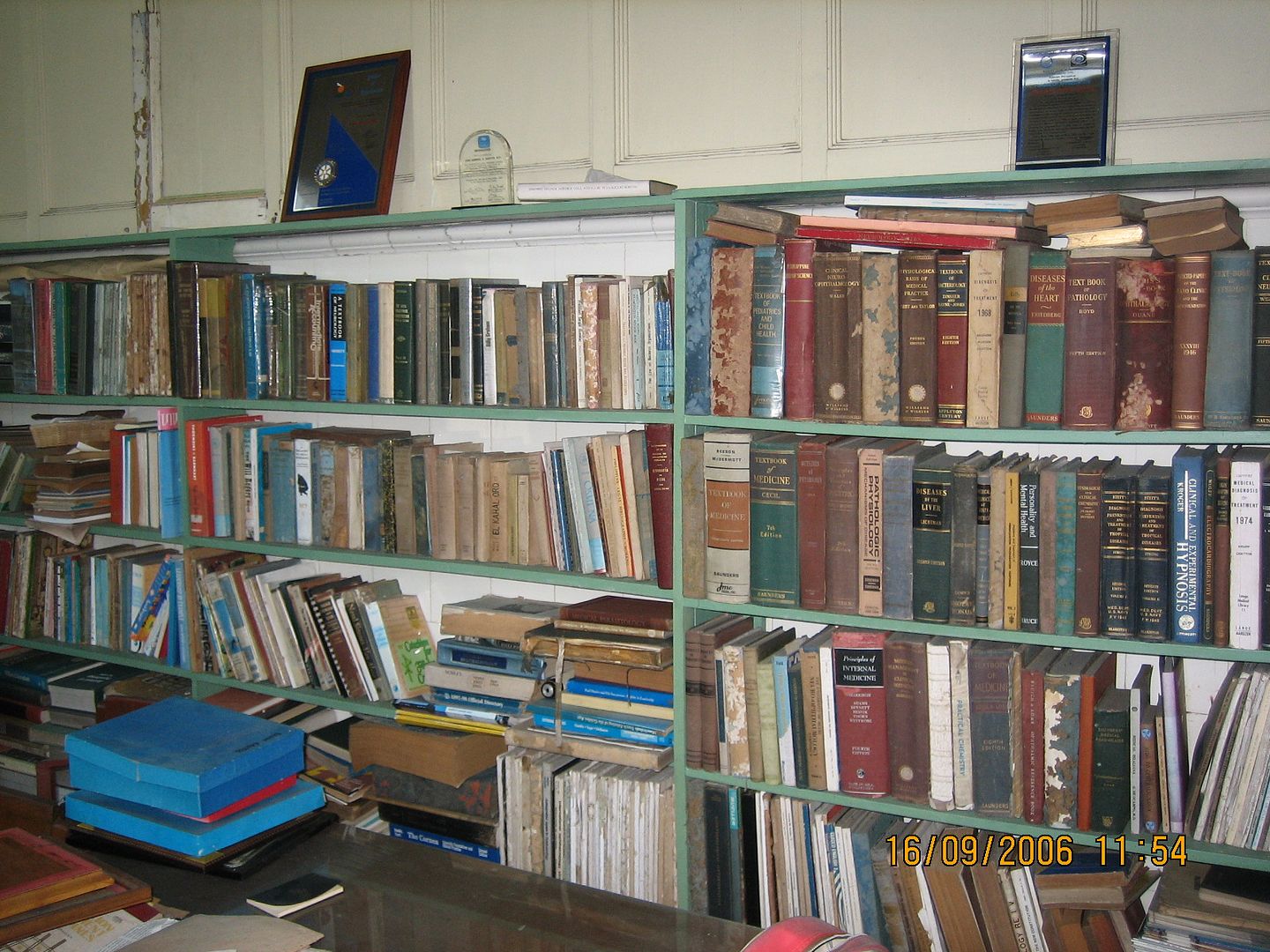

It would be neither unintelligent nor wrong to guess that this was the Santos Clinic’s original operating room from when the house was new. But since the Clinic had moved twice since, first to the separate building across the driveway, and then today way across town along the MacArthur Highway (where platoons of patients still show up daily for treatment by Dr. Luis’ son and grandsons, much like nearly a century ago when he was still actively practicing), the former O.R. is now a storeroom for furniture, medical books, and other family papers.

Among the pile of stored objects was a painting of Christ Healing the Blind, certainly a staple in many eye doctors’ personal art collections the world over.

Back in the foyer outside, we go past the screen and under this elaborate archway

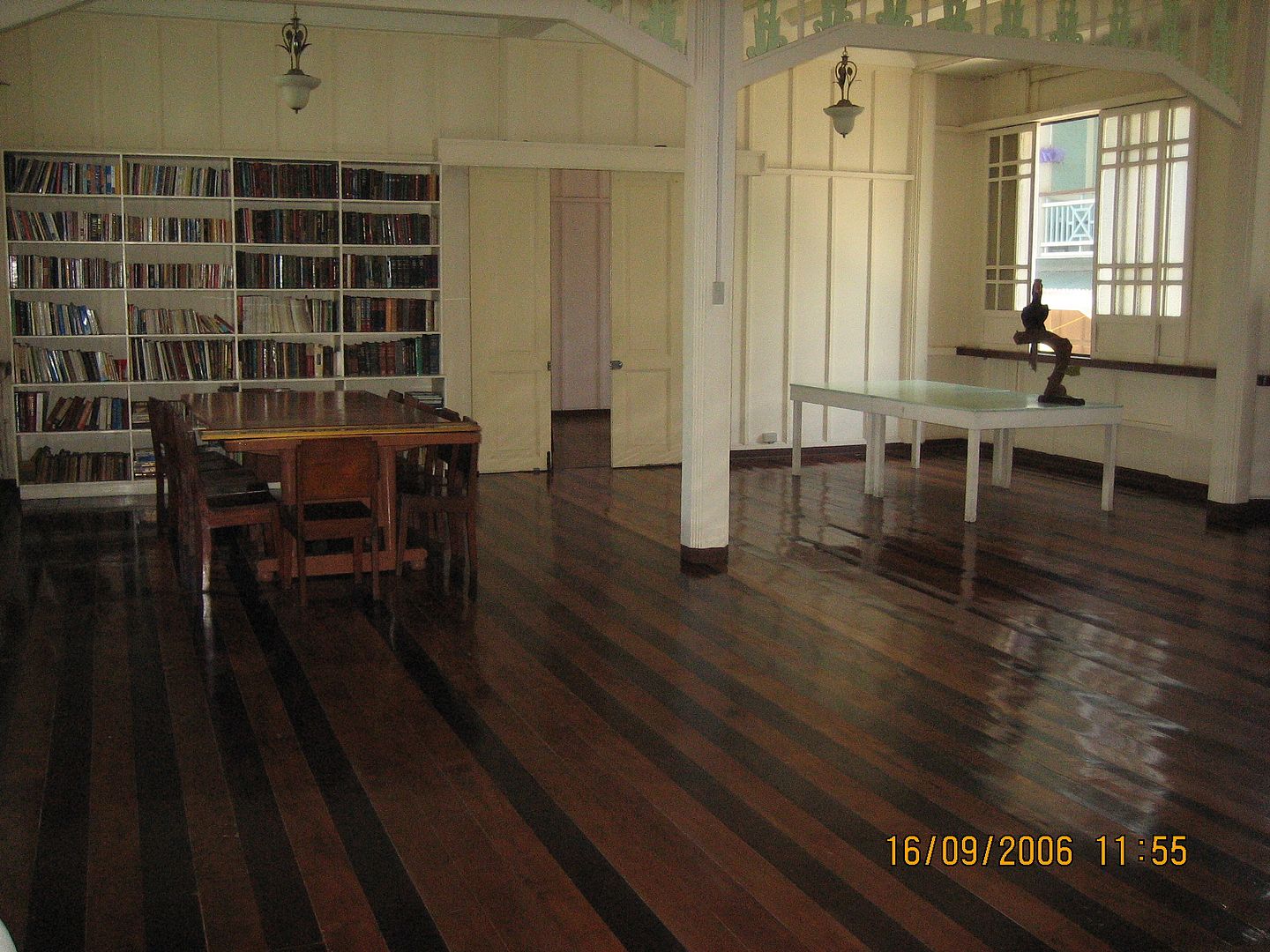

and emerge towards the left side in a large open hall with a beautiful wood floor with alternating light and dark-colored planks.

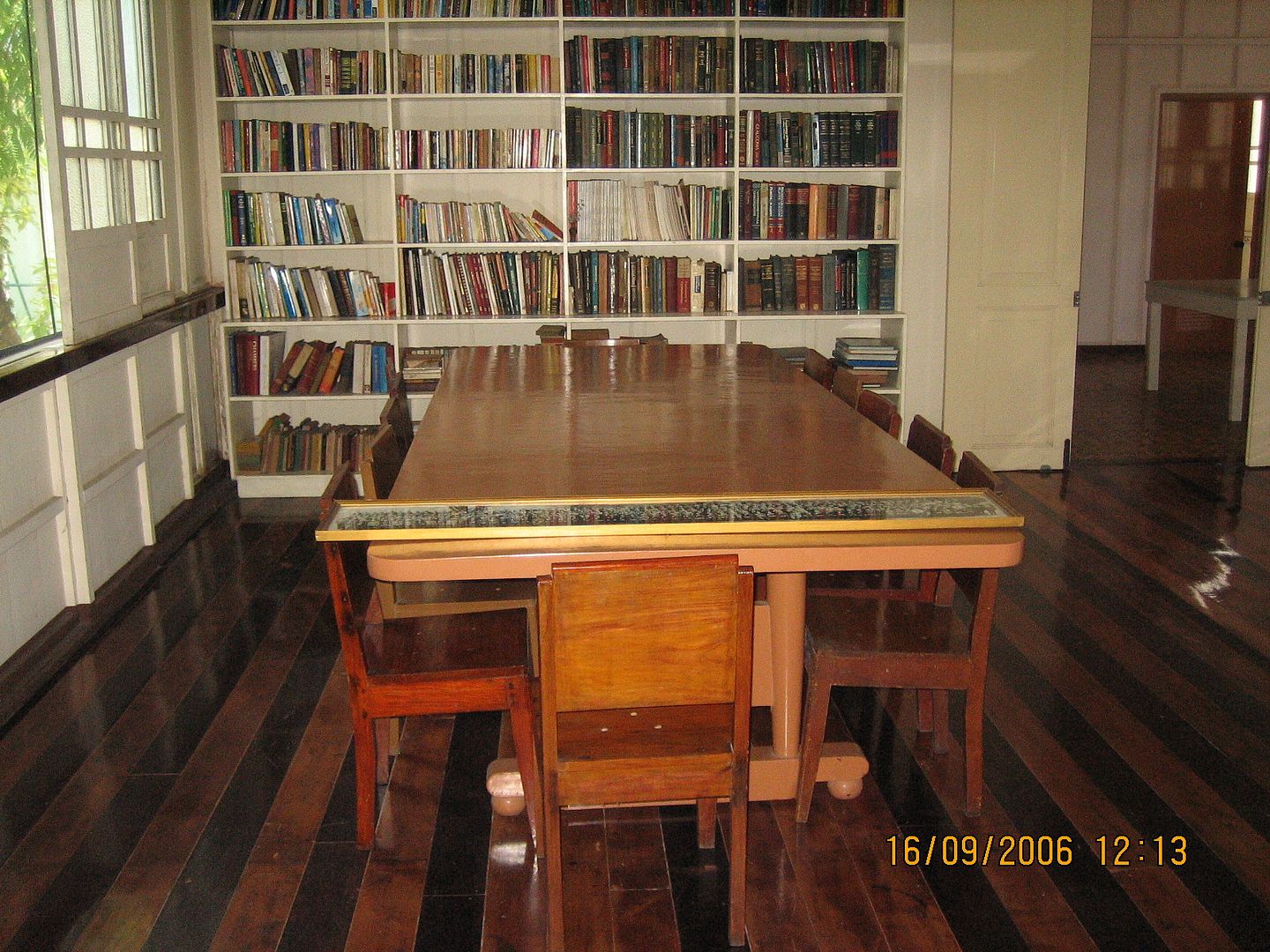

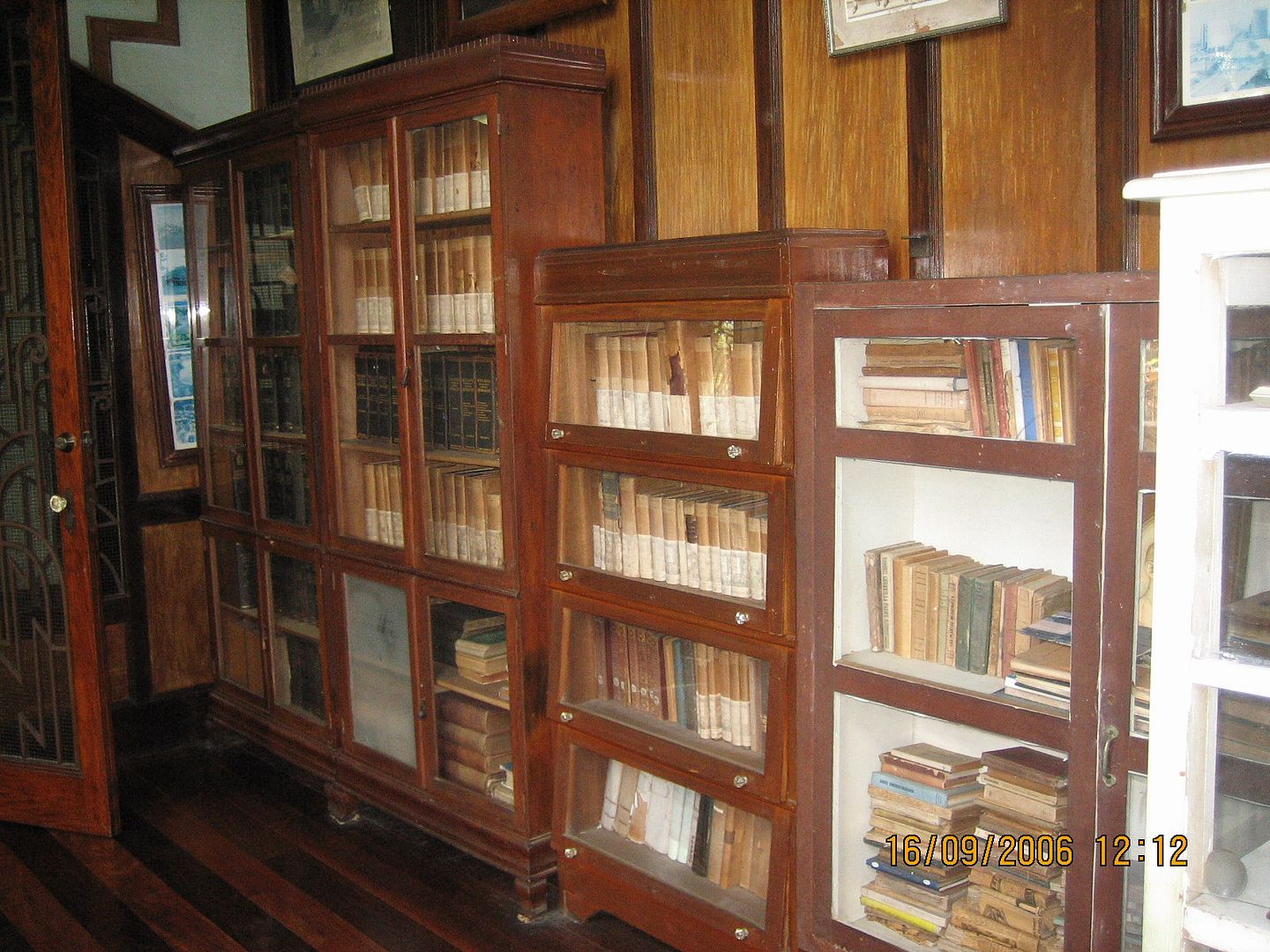

Originally, this space, right next to the OR, was subdivided and served as the wards for surgical patients in preparation for or in recovery after surgery. After the transfer of the medical facilities to the adjacent building, this had become a multipurpose hall, with an entire wall of books and what looks like a library table on the far end

plus plenty of space to display pieces from the family’s antique furniture collection, including a three-seater settee and a carved Chinese chest,

a pair of Art Deco rocking chairs,

and a pair of mini-sized sideboard cabinets,

And this wall is adjacent on the far end to a set of sliding-panel windows with frosted and glazed glass panes that look out onto the driveway in front.

Further down beyond a pair of sliding wooden doors is a simply-furnished bedroom, with a bed that is believably from the 1930’s,

as well as a typical Bulacan-style daybed / divan.

Nearby is another tile-floored room

that holds more disused furniture, including this four-seater settee (that thankfully [and partly upon my instigation] was thoroughly restored shortly after this visit)

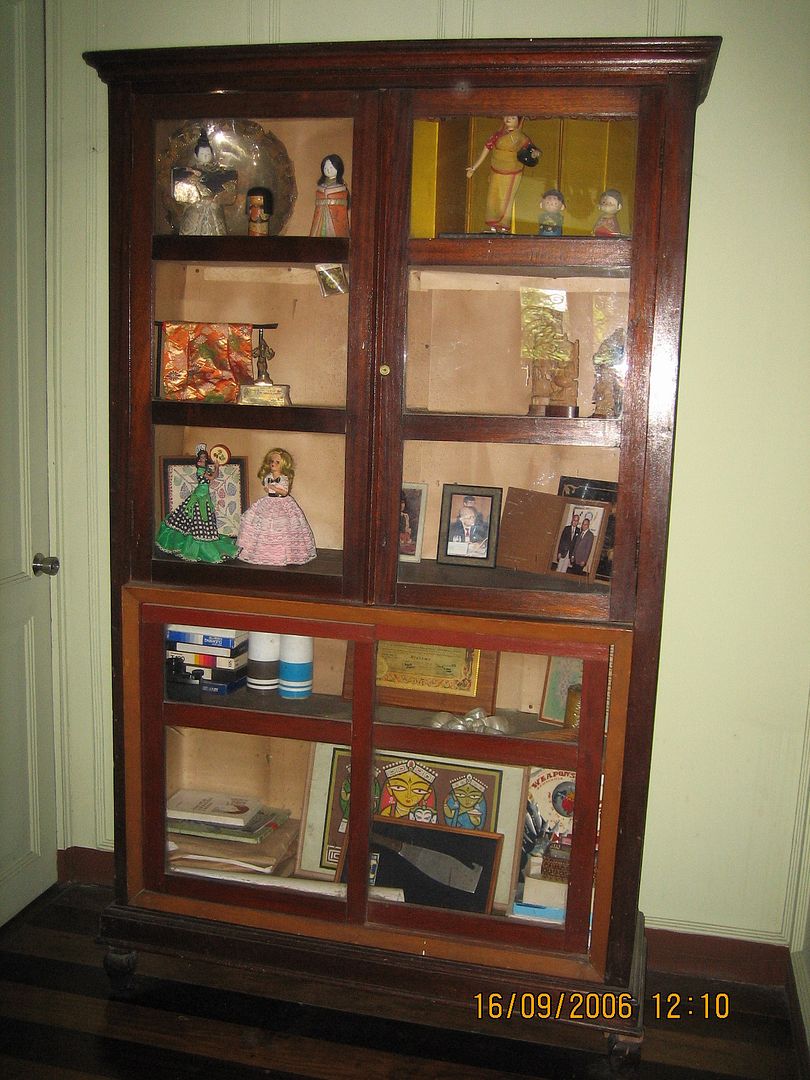

Back in the near end of the ground floor, after the foyer, stands a bookcase that now holds family souvenirs and other trinkets.

Right next to it is a door to a room, now also a bedroom but originally what is likely to have been Dr. Luis’ office.

Back in the foyer, we consider going back out onto the entrance balcony and taking the door on the right that leads to the private residence. However, that is totally unnecessary as one can cross over easily to the residence’s vestibule from just outside the O.R. in the background of this next photo

and right under a portrait of the good doctor in academic gown.

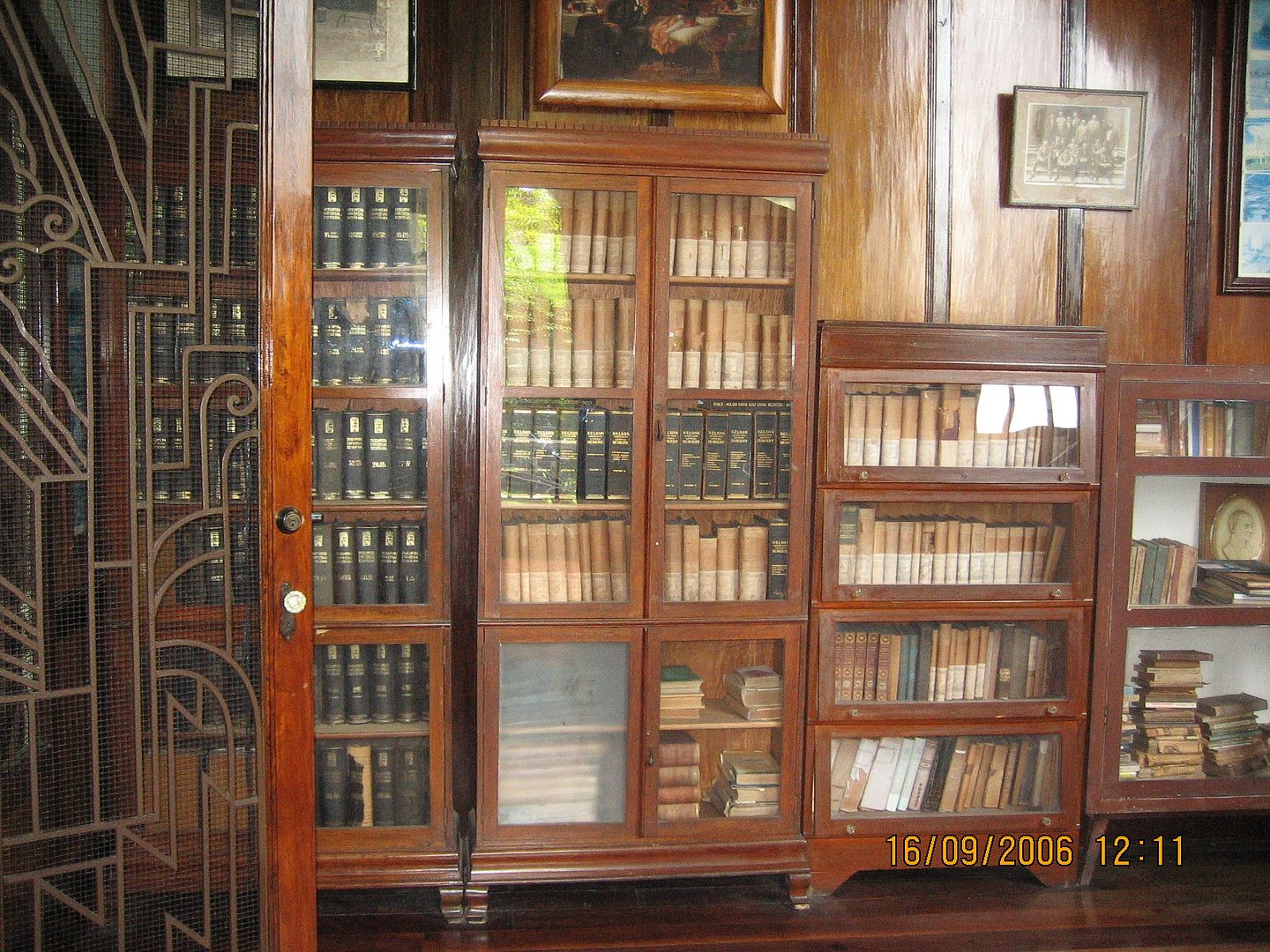

In this vestibule stands more glazed bookcases in different configurations, holding even more of Dr. Luis’ medical references.

There are also some shorter cabinets with what appear to be medical and scientific equipment, as well as cabinets with bright yellow satin curtains that only add more mystery to what is already a fairly interesting visit.

The clincher was this small door. What lay on the other side I didn’t have the heart to find out. The midget nurses’ bedroom?

Actually it just allowed access to a storeroom under the grand staircase. Or so I hope. We make an about-face to the foot of the staircase, and note this crucifix on the wall in between the bottom of the stairs and the main entrance. I guess it functioned like a holy water font, to bless oneself before leaving and upon arrival, but without the holy water.

The staircase itself is truly grand, and a touch intimidating.

Especially for the end of the colonial era, it cannot be accused of not being wide enough.

And for good measure, in case a haughty visitor shows up, the oversized newel post is as exuberant as it gets for the flamboyant 1930’s. What Great Depression?

I’m not as familiar with Classical Mythology as I should be, so is the newel post topper a rendition of Athena or somesuch?

At any rate, she provides illumination for safe ascension on cloudy days and dark stormy nights.

I ascend the stairs

and view the vestibule from the intermediate landing,

where a bust of Dr. Luis (made for him by a grateful eye patient-sculptor) sits in one corner, to welcome visitors.

From the landing, we look up to appreciate the ornate staircase ceiling

with integrated light bezels.

The landing is directly illuminated during the daytime by floor-to-ceiling glazed panels

with stained glass ornamentation even.

Around the bend after the landing, from which we can have a sneak preview of the second floor through the ornate Art Deco balusters,

is the final flight of steps

before we reach the head of the stairs.

The pair of newel posts at the top is not as flamboyant as their solo partner down below, presumably because the staircase knows that no one doubts its Art Deco credentials any longer, plus anyway there are two of them this time, one on each side.

And if there are any more doubters about those credentials, the balusters have been fully-figured to inimitable detail.

Right by the top of the stairs and directly behind the balusters is Dr. Luis’ desk

and his swivel chair is nearby.

To the left of the desk is a double door that leads to an outside balcony.

The desk and swivel chair are just two pieces of furniture in the corner of a vast living room, with not just one

but two original and unique ambassador sala sets.

The space between the two sala sets shows off the floor’s rich assemblage of geometrically-cut wood planks in various shades and types of Philippine hardwood.

But it is when one looks up that the acknowledged star of the show is revealed.

For the Dr. Luis Santos House is the proud home of a large ceiling painting by the renowned Fernando Amorsolo (1892-1972), commissioned by the good doctor directly from the artist, who was likely one of his many grateful eye patients. Even here, the house's Art Deco idiom asserts itself in the painting's framing and ceiling ornamentation.

Never departing from the style, the living room space is lit by wall-mounted Art Deco slipper shades.

Off to one side, past one of the Ambassador sets and beside the desk and swivel chair, is an upright piano.

Dr. Luis not only had fine taste but was also a good judge of quality, for German pianos – Steinweg, Grotrian, and Zeitter & Winkelmann – were the best. For his personal use, he chose an upright Zeitter & Winkelmann

with not only beautifully-figured wood veneering but also brass candlesticks.

What I found more interesting though is this painting right above the piano.

Actually, it’s not a painting but merely a faded photocopy of the original oil on canvas that hung in this same space, entitled “Kundiman,” commissioned by Dr. Luis in 1932 from Amorsolo’s uncle and mentor, Fabian de la Rosa (1869-1937), also one of the doctor’s satisfied eye patients. It depicts, among others, Dr. Luis himself in the left foreground, wearing a white suit, and his younger sisters among the audience members, listening to a piano-accompanied serenade sung by a soprano. The painting was unfortunately part of a trade to restore the Amorsolo ceiling painting some years back, and is now in the Paulino Que Collection.

So far, we have seen evidence of the good doctor's artistic good taste. In addition, like most of the high-born Filipinos of his generation, Dr. Luis and his family were also religious - his mother Alberto Uitangcoy-Santos and his sisters were daily mass goers, and I would see Dr. Luis himself attend Sunday late morning mass at the Cathedral in his latter years, already in a wheelchair, but obviously constantly giving thanks to God for having been granted a long, full, and rewarding life.

So it should come as no surprise that his home would have its own private chapel, just adjacent to the living room, opposite the staircase and past the Amorsolo ceiling painting. It is entered via a double-paneled glazed door with stylized wrought-iron Birds of Paradise, which, I by now realize, is a common design shared by all of the double doors on the second floor.

So far, we have seen evidence of the good doctor's artistic good taste. In addition, like most of the high-born Filipinos of his generation, Dr. Luis and his family were also religious - his mother Alberto Uitangcoy-Santos and his sisters were daily mass goers, and I would see Dr. Luis himself attend Sunday late morning mass at the Cathedral in his latter years, already in a wheelchair, but obviously constantly giving thanks to God for having been granted a long, full, and rewarding life.

So it should come as no surprise that his home would have its own private chapel, just adjacent to the living room, opposite the staircase and past the Amorsolo ceiling painting. It is entered via a double-paneled glazed door with stylized wrought-iron Birds of Paradise, which, I by now realize, is a common design shared by all of the double doors on the second floor.

As the chapel is directly above, and is the same shape as, the Operating Room on the ground floor, it is spacious and welcoming.

Reflecting the floor plan, the ceiling is an exuberant Art Deco octagon with a light fixture in the center.

still very much in the Art Deco idiom.

Visiting priests, bishops, and cardinals will certainly fall over themselves to get the opportunity to officiate a private mass for the good doctor and his family at an altar as splendid as this -- and I was told that a fair number have (officiated mass, not fallen over).

The altar image is a statue of Our Lady of Lourdes, reportedly imported from France, but probably already repainted since new.

Around the perimeter of the chapel are other images – a version of the Santo Niño de Malolos in its own urna

and smaller images for private devotion on an antique comoda.

There was also a double-mirrored aparador beside the door – perhaps for storing the garments of clothed religious images?

Right outside the chapel door was a large image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, rendered in a 20th century style, certainly Art Deco-compatible.

At this point, the already shell-shocked visitor might wonder (1) who designed all the woodwork in this house, from newel post, to balusters, to ceiling, to floor, to altar table, and (2) where did all the wood come from?

The answer to the first equation is that, obviously, a master architect entirely fluent in the Philippine Art Deco idiom of the 1930's was engaged by Dr. Luis, whose good taste (no doubt cultivated overseas in the course of medical studies in Spain and at the Johns Hopkins University in the USA) only needed putting on paper and actual execution. Unfortunately Dr. Benny could not recall who his father's architect was, but it was probably one of the prominent names of the period, like Juan Arellano, Pablo Antonio, Juan Nakpil, or Andres Luna de San Pedro.

The answer to the second question is that Dr. Luis' wife, Fermina Bello, was a wealthy heiress from the Bicol region. The wood was sourced from the forests in her home region, shipped north through Manila Bay, and transported upstream in cascos (narrow cargo boats) directly to the construction site via a creek, now partly filled in and mostly clogged, that used to run right beside the house. Skilled local carpenters and carvers then worked the wood onsite following the architect's detailed designs, resulting in the coherent shrine to the Art Deco style that is Dr. Luis' house.

We keep going and walk beyond the living room, under another elaborate archway

The answer to the first equation is that, obviously, a master architect entirely fluent in the Philippine Art Deco idiom of the 1930's was engaged by Dr. Luis, whose good taste (no doubt cultivated overseas in the course of medical studies in Spain and at the Johns Hopkins University in the USA) only needed putting on paper and actual execution. Unfortunately Dr. Benny could not recall who his father's architect was, but it was probably one of the prominent names of the period, like Juan Arellano, Pablo Antonio, Juan Nakpil, or Andres Luna de San Pedro.

The answer to the second question is that Dr. Luis' wife, Fermina Bello, was a wealthy heiress from the Bicol region. The wood was sourced from the forests in her home region, shipped north through Manila Bay, and transported upstream in cascos (narrow cargo boats) directly to the construction site via a creek, now partly filled in and mostly clogged, that used to run right beside the house. Skilled local carpenters and carvers then worked the wood onsite following the architect's detailed designs, resulting in the coherent shrine to the Art Deco style that is Dr. Luis' house.

We keep going and walk beyond the living room, under another elaborate archway

toward what was the family’s private dining room

with a large-diameter round dining table,

matched to twelve of these chairs

and an enviable single-piece top.

If there were more diners than twelve, the spillover was this older rectangular dining table, with an equally intimidating single-piece top.

The room was illuminated by this funky modern chandelier.

Here also stood a tall-case pendulum clock

and against one wall was a large built-in platera

which backed on to its exact twin in the adjacent kitchen

which, as it was no longer in regular use,

was simply furnished.

Beyond the dining room and adjacent to the kitchen was a small bedroom, accessed via these doors

directly under this transom.

Within this room were more disused antique furniture, including a wooden bed and a steel bed, both antique,

a butaca or lounging chair

and a tres-lunas tocador or three-mirrored dresser

Illumination was simple, with the original lamp shade now missing.

Beyond the kitchen, past an open passageway, and by these wrought iron window grilles

is a door

that allows access to a spiral staircase

that leads to a tower room

that Dr. Luis had built so that he could gaze across the neighborhood

and play his violin by the light of a single light bulb

or simply lounge in this ambassador armchair (subsequently refurbished after my visit).

The three-storey high tower, which was part of a post-war renovation and also included the double-doored garage below, looks like this from the outside.

We make our way back downstairs to the kitchen and dining room, past the archway

and towards the living room once again

and knock on the master bedroom door off to the left side, beside the upright piano.

Dr. Luis is unfortunately no longer around to open the door for us, but his aparadors are still in place

and someone seems to be asleep in his bed.

Pulling back the covers, we find that it’s just Malolos’ life-sized processional image of the Dead Christ.

The original owner of this Santo Entierro image was a wealthy unmarried lady named Francisca Tantoco (1837-1920), who also owned the original image of the Santo Niño de Malolos. After she died, the images were given to relatives who were thought to be capable of caring well for them. Thus, the smaller Santo Niño (see here) was inherited by her nephew Dr. Angel Santos Tantoco, a dentist, and the large Santo Entierro went to another nephew, Dr. Luis Santos, who was probably already by then adjudged to be quite successful and prominent in the community despite his relative youth and only recently-established practice. Dr. Luis and his heirs have thus been the custodians ever since of this Santo Entierro, used in the Malolos Cathedral’s Good Friday procession each year.

(However, I do think that this image of the Dead Christ would be better off being stored and displayed for veneration in, for example, a custom-made wood-and-glass case inside the house's private chapel, rather than under blankets in Dr. Luis' bed!)

Opposite the master bedroom across both ambassador sala sets are a pair of double doors, neatly mirroring the pair of main entrance doors directly underneath on the ground floor. Each double door was topped by its own stained glass panel, depicting allegorical figures.

(However, I do think that this image of the Dead Christ would be better off being stored and displayed for veneration in, for example, a custom-made wood-and-glass case inside the house's private chapel, rather than under blankets in Dr. Luis' bed!)

Opposite the master bedroom across both ambassador sala sets are a pair of double doors, neatly mirroring the pair of main entrance doors directly underneath on the ground floor. Each double door was topped by its own stained glass panel, depicting allegorical figures.

This lengthy and mind-blowing tour around what is not really an enormous house had by now given me a mental overload, what with so much 1930’s opulence and so many visual details plus all the background stories to take in. I think that Dr. Benny must have sensed my brain fatigue, which is why he invited me to walk through one of the two sets of double doors

that looks like this from the outside

and come sit with him outside on the balcony,

from where we could take in a good view of the driveway, garden, and fountain sculpture

while he told me more stories about his father and his father’s house.

After a long while had passed and with me wondering if perhaps I was not detaining him unnecessarily (it did not appear so, as he seemed to be thoroughly enjoying reminiscing about his father and his father's times), I prepared to bid my leave. He however said that there had to be one last stop on this visit, and that was the rear of the house.

After a long while had passed and with me wondering if perhaps I was not detaining him unnecessarily (it did not appear so, as he seemed to be thoroughly enjoying reminiscing about his father and his father's times), I prepared to bid my leave. He however said that there had to be one last stop on this visit, and that was the rear of the house.

where not only was there a purpose-built smaller house, towards the left in this next photo

where the servants lived and all the meals were prepared, but also a special garage where was stored the calandra (funeral coach) of Dr. Luis’ Santo Entierro heirloom.

This appeared to be made of balayong, the same kind of dark tropical hardwood used in many places throughout the house, and decorated with silver appliqués and other adornments.

Its size and style however do not appear to be contemporaneous with the image, which if its original owner Francisca Tantoco was born in 1837, must date from the middle of the second half of the 19th century. Instead, this calandra looks vaguely Art Deco-influenced Neoclassical to American colonial to me.

I’m guessing that Dr. Luis had this calandra made after he inherited the image, using balayong wood that he was anyway accumulating while preparing to build his house.

A final clue is the lower part of the calandra's body, which features angel heads set amongst clouds, carved in wood and then painted.

A final clue is the lower part of the calandra's body, which features angel heads set amongst clouds, carved in wood and then painted.

These look not too dissimilar from those on the silver-plated chariot-style “carroza triunfal” still used today by Malolos’ processional image of the Immaculate Conception each feast day on December 8th (see here). That grand carroza, originally commissioned by Felix Bautista from neighboring Barangay Santo Rosario, is throught to date from the 1920’s, which might indicate that Dr. Luis had commissioned this calandra from the same maker (reputedly the Maximo Vicente Workshop in Manila in the case of the carroza triunfal).

- - - - - - - -

By this time I had definitely gone over my daily recommended dose of ancestral houses, antiques, religious images, and carrozas - all from just this one visit - and it was time for me to bid my leave and thank Dr. Benny for his extreme generosity and warm hospitality.

As it turned out, this was to be the last time that I would ever speak to Dr. Benny, for he had died in his sleep the following January (2007). This made me feel double-blessed, for having been able to privately visit the good doctor's house, still the most beautiful and most gracious -- and indeed most literate, educated, and sophisticated -- pre-war home in not only my hometown but also quite possibly in the entire country, and for being hosted by his good son.

Would anyone in my situation not feel the same?

Originally published on 14 November 2010. All text and photos copyright ©2010 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.- - - - - - - -

By this time I had definitely gone over my daily recommended dose of ancestral houses, antiques, religious images, and carrozas - all from just this one visit - and it was time for me to bid my leave and thank Dr. Benny for his extreme generosity and warm hospitality.

As it turned out, this was to be the last time that I would ever speak to Dr. Benny, for he had died in his sleep the following January (2007). This made me feel double-blessed, for having been able to privately visit the good doctor's house, still the most beautiful and most gracious -- and indeed most literate, educated, and sophisticated -- pre-war home in not only my hometown but also quite possibly in the entire country, and for being hosted by his good son.

Would anyone in my situation not feel the same?

Original comments:

overtureph wrote on Nov 15, '10

Wow! Thanks for sharing this....I've always been curious as to what the interior looks like as well as the Amorsolo painting. I've also been to a house in Malabon whose ceiling was reputedly painted by Amorsolo. I'll try to post it too.

Very impressive house. |

arcastro57 wrote on Nov 15, '10

It's so well built and well-kept--it's like the doctor never left.

|

rally65 wrote on Nov 15, '10

Yes, I've heard about that Amorsolo ceiling painting in Malabon. Please do post photos so we can take a look.

I read somewhere that Amorsolo also painted the ceilings of a church in Daet, Camarines Norte (where he spent his earlier years). But apparently they no longer exist today. |

rally65 wrote on Nov 15, '10

Although the house has been uninhabited since Dr. Luis' widow died some years after he himself died in 1982, there are caretakers who still live in the separate structure in the back. (Dr. Benny did not live here as he had his own home elsewhere in Malolos as well as in Quezon City, and would just visit and check on things occasionally.)

The caretakers ensure that the place is kept clean, although it would be much better for the house's sake if it were actually lived in. (I volunteer to do so! Ha ha ha. Seriously.) |

arcastro57 wrote on Nov 15, '10

Ok, put me on the 2nd priority list!

|

jamaica1ph wrote on Nov 16, '10

Leo, I fell in love with this house when I visited it in the early 90's. The santo entierro used to be in a bed in the family chapel if I remember it right. Did you not go to the bathroom with the wall paintings also said to be by F. C. Amorsolo?

Thanks for documenting it. |

rally65 wrote on Nov 16, '10

Unfortunately I didn't get to visit the bathroom and photograph the Amorsolo wall paintings. If I get to visit again, I will do so.

I do hope they commission a wood-and-glass case for the Santo Entierro and put it in the chapel instead. |

mienaichizu wrote on Nov 16, '10

Wow! I only saw a few photos of this house in some books, didn't imagine how beautiful it is inside

|

rally65 wrote on Nov 16, '10

You should try to visit too sometime. Architects always freak out when they see the interiors!

|

mienaichizu wrote on Nov 17, '10

I'm already freaking out when I saw your photos. Very ornate, intricate Art Deco styling!

|

rally65 wrote on Nov 17, '10

Make sure you take a tranquilizer before you visit.

|

cymeii wrote on Sep 16

good day sir, i would like to ask if this house is a bahay na bato? if ever, where i can find this? thank you.

|

rally65 wrote on Sep 16

This house is in Malolos, Bulacan, as the title of the article says.

|

4 comments:

We visited the house when I was in design school in 1989. The dead Christ used to be on a bed in the chapel and not in the master bedroom. Did you not go to the bathroom with walls also painted by Amorsolo? -mike caling

Thanks for reading, Mike. Yes, I got to see the Amorsolo-walled bathroom but only on a subsequent visit, so that is not included in this narrative. In fact, I had visited this house perhaps a dozen times since this first visit. Still my favorite house in Malolos.

Hard to believe- but my elder brother, Nony, and I were surgical patients of Dr. Luis Santos around 1940. The surgery was not on the eyes, but on our private parts.

Thank you very much for your reminiscence of Dr. Luis. Even my mother and her siblings had several. He was certainly much-loved in Malolos and beyond.

Post a Comment