I had already visited the old church in the Bayan of San Rafael, Bulacan on Holy Wednesday in 2007, and wrote about it here. Unfortunately, it was not a good occasion to explore the inside of the church in detail, since there were simply too many devotees inside, and besides all the church images were shrouded, in keeping with Holy Week custom. Thus, all of the photographs that I took on that day were of the parish’s processional images, which was just as well as that was my primary objective anyway then.

This past All Saints’ Day, however, I was in the neighborhood again, as our family mausoleum is just a few hundred meters behind the church. After spending some hours in the cemetery, I walked back to the churchyard because we were parked there, but instead of taking off for home immediately, I tried to force my way into the deserted church.

Fortunately I didn’t really have to do any forcing, since the main door of the church was open, and one of the caretakers graciously welcomed me in. Thus, I was able to walk right up to the main altar, and have an unobstructed view of the tastefully-restored-and-updated neoclassical (or baroque) retablo.

In the top niche is a Marian image, visible in the photo above, but too high up to be photographed well by someone on the floor. It appears to me to be an image of Our Lady, Mary, Mediatrix of All Grace, as she appeared (in 1948), and continues to be venerated, in the Carmelite Monastery in Lipa, Batangas.

In the center niche is this life-sized crucifix, apparently a new well-made piece.

This is flanked by the town’s two patrons – on the left, the town’s namesake, Saint Raphael the Archangel

and on the right, the founder of the Hospitaller Order that became the administrator of this parish in the 18th century, Saint John of God.

The retablo is flanked by these light-bearing angels, on the left

and on the right.

I only wish that they had managed to conceal the electric wires somehow – if not inside the statues themselves, perhaps more carefully affixed to the backs of the images so as to keep them out of sight.

And if that illumination was insufficient, more light-bearing angels were positioned high up on the sides of columns in the altar area.

There were also the standard images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus

and the Immaculate Heart of Mary

flanking the altar on the left and right front corners respectively.

The San Rafael Church is in the form of a Latin cross, with the arms accommodating spacious side altars. The left side altar’s retablo consists of an image of the “Our Lady of the Holy Rosary of San Rafael” in the center

flanked by the Blessed Virgin Mary’s parents, San Joaquin on the left

and Santa Ana on the right.

Nearby was a painted-wood relief of Our Mother of Perpetual Help.

And against the left-side wall was this life-sized processional Marian image, in its own glazed urna.

The right side altar retablo featured Saint Joseph (with this toolbox) in the center

with (a heavily-armed) Saint Paul on the left

and, predictably, Saint Peter (with humongous keys) on the right

Against the right-side wall in this space is the processional image of an unidentified female saint, perhaps a Holy Woman of the Passion.

Just off to the left side of the altar is a door that leads to the sacristy, which is interestingly furnished with what appears to be a deep and wide five-drawer antique vestry cabinet

above which hangs a life-sized Crucifix, presumably the antique that originally hung above the main altar.

Its corpus had since been repainted, but is still garbed in a fabric loincloth and topped with a wig.

Against one wall of the sacristy stands a marble washbasin, perhaps more decorative than functional, flanked by a pair of brass (plus one wooden) candlesticks.

My main objective in entering the San Rafael Church on this All Saints’ Day was not really to examine the religious images inside. Rather, I had noticed from previous visits that there were quite a number of tombstones within its walls.

These were gravestones, not for full-body burials in the walls and floors of the church – for that would pose quite a number of structural and logistical problems – but simply to mark the locations where the bones of certain prominent parishioners were interred after their transfer from the parish cemetery, which in the old days was just in the churchyard outside.

Therefore in keeping with the usual practice for the day, I wanted to pay my respects to the people interred within, even though I did not think I knew any of them. Besides, with all my maternal relatives tracing their origins to San Rafael, a number of these bones now permanently ensconced in the floors and walls of the church might even share some of their DNA with me.

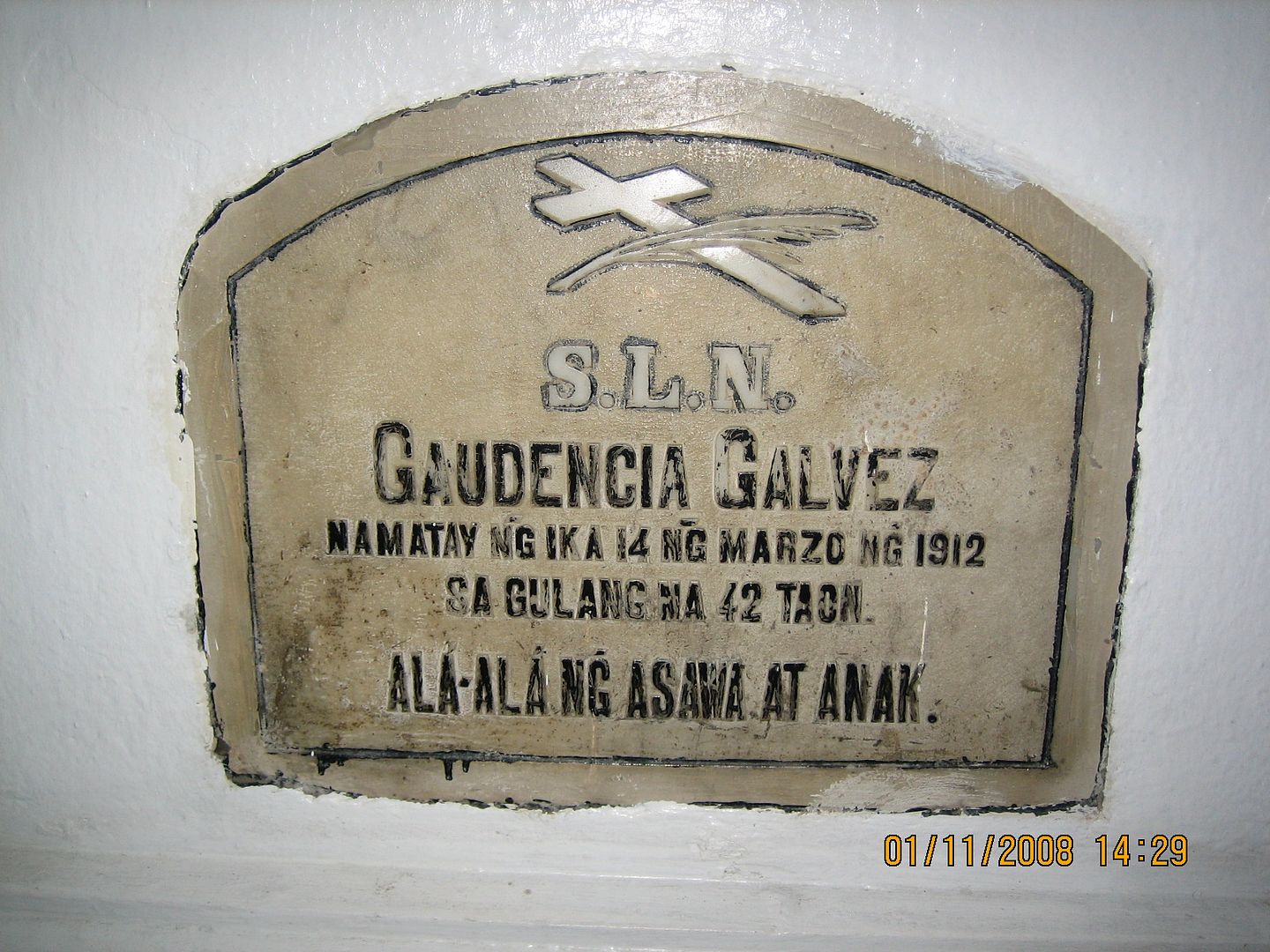

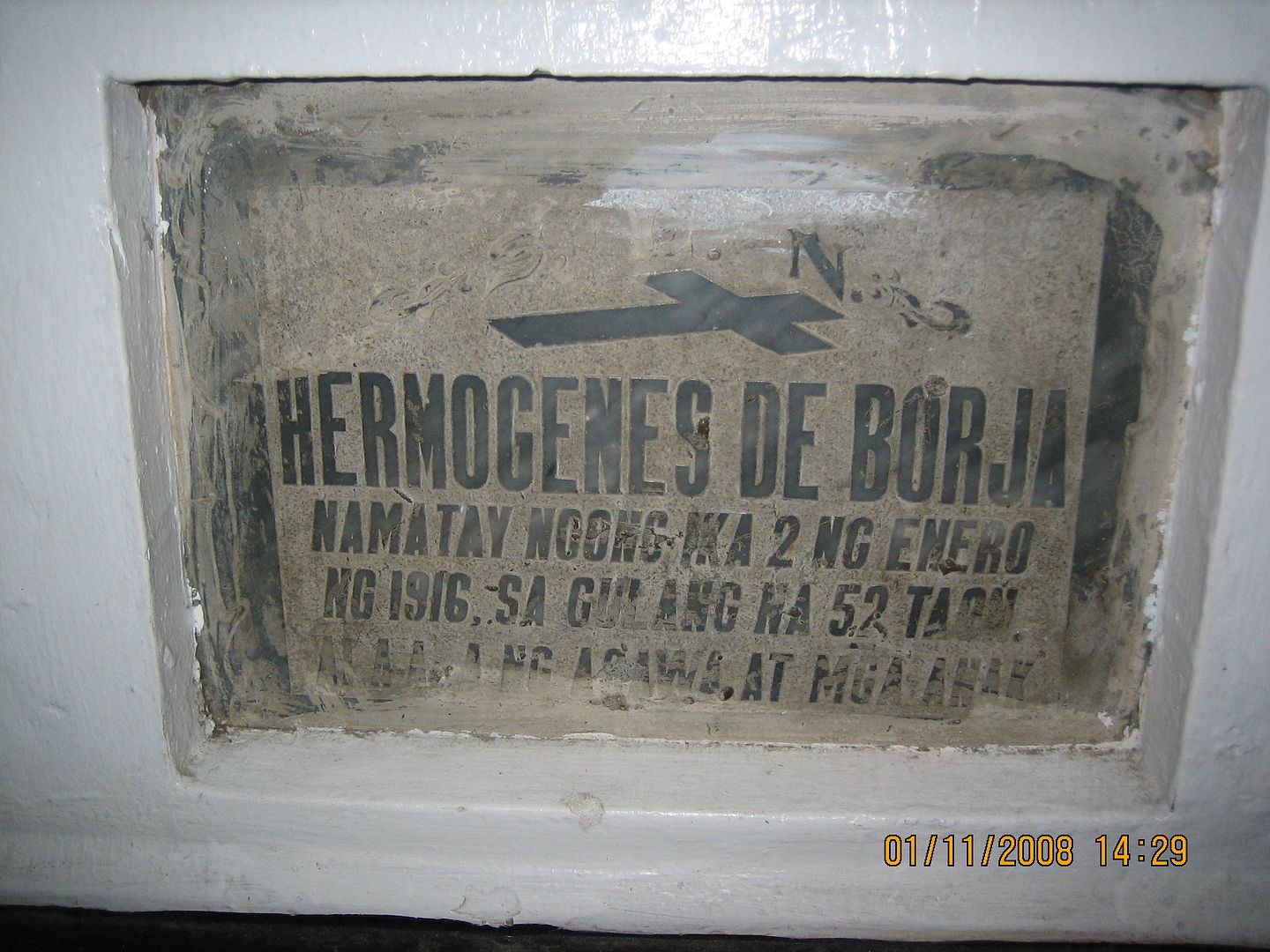

The other thing with these marble markers is that no two were really alike. Nowadays, lapidas in the cemeteries tend to be all exactly the same size and rectangular shape, and the fonts and decorations thereon come in just a handful of predictable variations. In contrast, these century-old examples are wonderfully creative in design and execution, each one unique, as shall now see.

Starting from the right-side wall near the main entrance, we have a marble marker for Gaudencia Galvez, who died on 14 March 1912 at the age of 42.

Then we have Hermogenes de Borja, who died on 2 January 1916 at the age of 52.

Next is Guillermo Viola, who was 60 years old when he died on 22 October 1915.

A large arch-topped marker was commissioned for the remains of Don Flaviano de Mendoza, who died on 12 September 1912 at the precise age of 73 years, 6 months, and 12 days.

The dedication in Spanish says roughly, “An eternal remembrance from his bereaved family.”

Stylized floral (gumamelas similar to those on Guillermo Viola earlier) and scroll decorations adorn the marker for Zacarias Bernaldo, who died on 24 April 1921 at the age of 37.

Quite a number of tombstones have unfortunately been swallowed up, partly or entirely, by the floor, which obviously had been raised since the decades when these tombstones were installed near the beginning of the 20th century. These two, for example, are now totally anonymous.

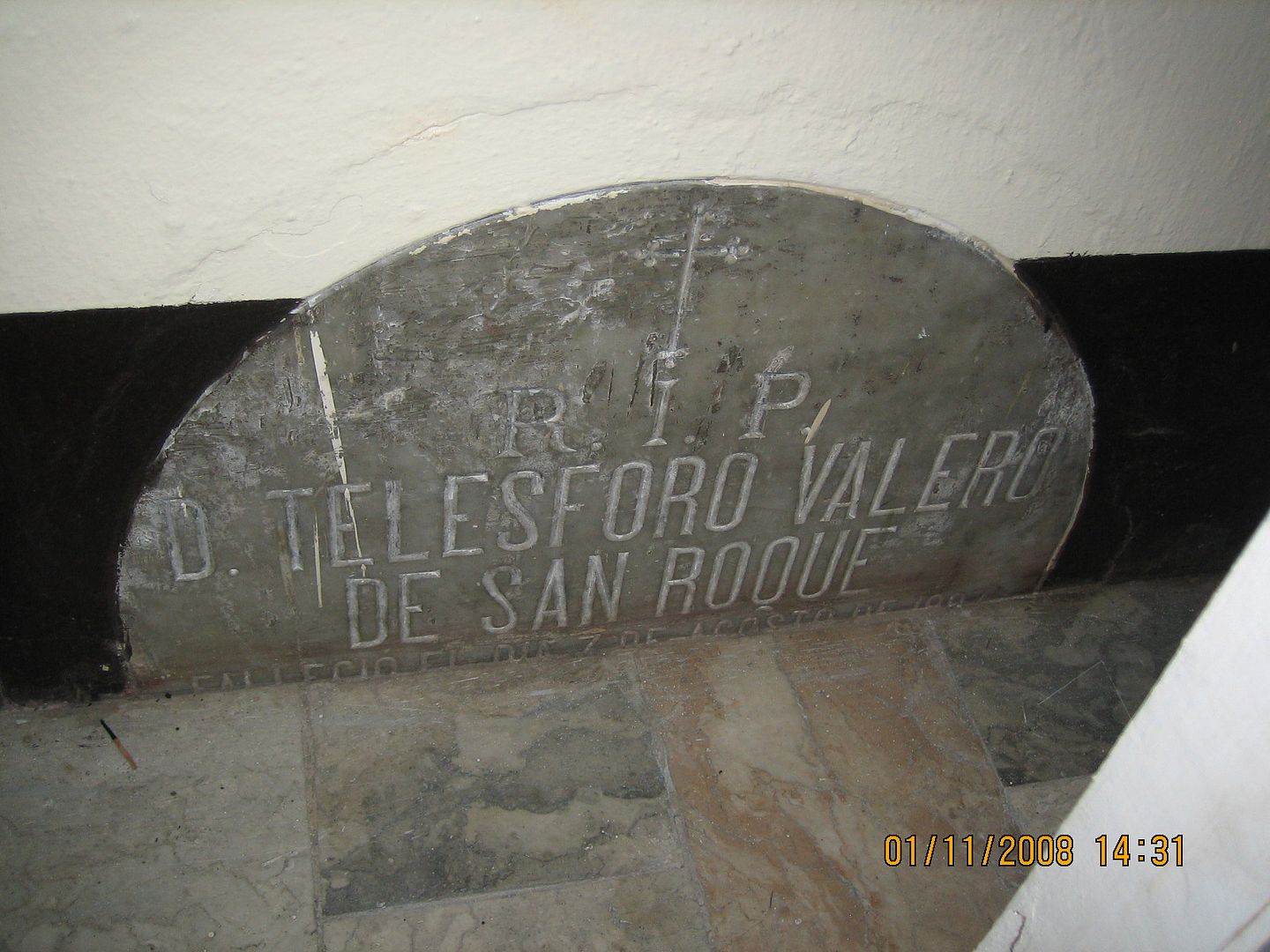

As for this one, we can’t clearly make out the date of death of Don Telesforo Valero de San Roque, although it seems to be August 7th of some indeterminate year.

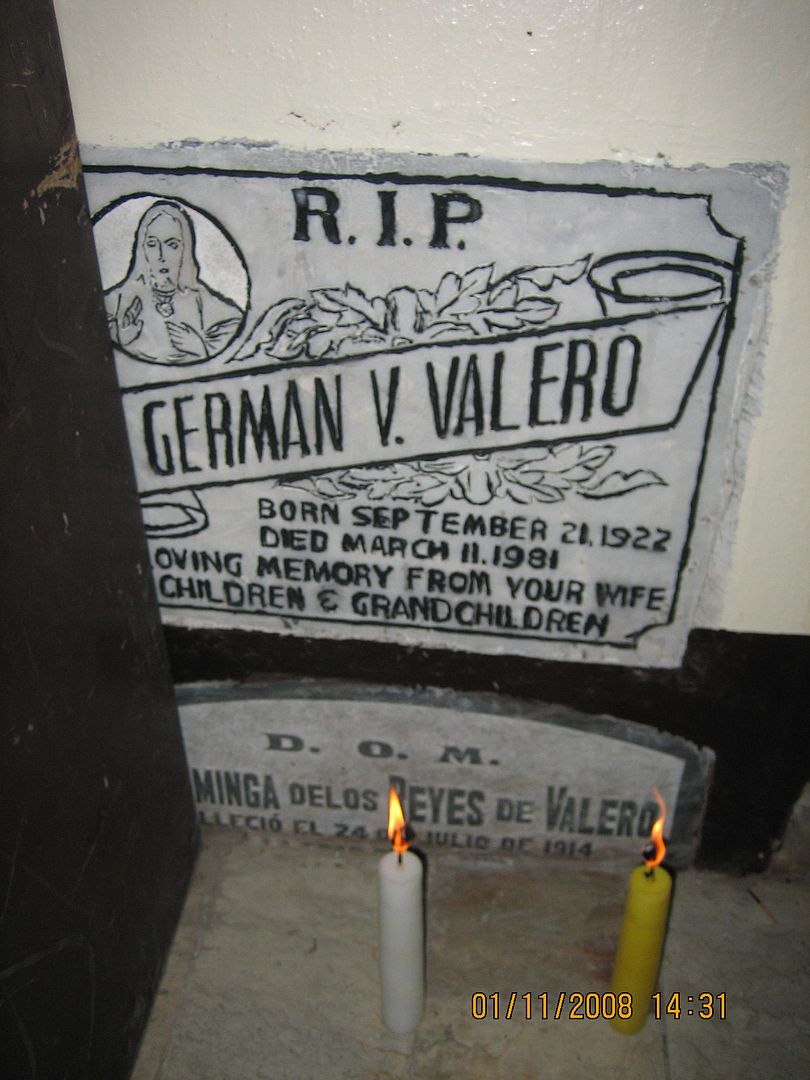

Nearby are the markers of what might be Don Telesforo’s relatives, a more recently deceased German V. Valero (21 September 1922 – 11 March 1981), above the partly submerged Dominga de los Reyes de Valero (who died on 24 July 1914). Likely due to German’s relatively more recent passing, their relatives still manage to light commemorative candles for them (though they were nowhere to be found when I was there.)

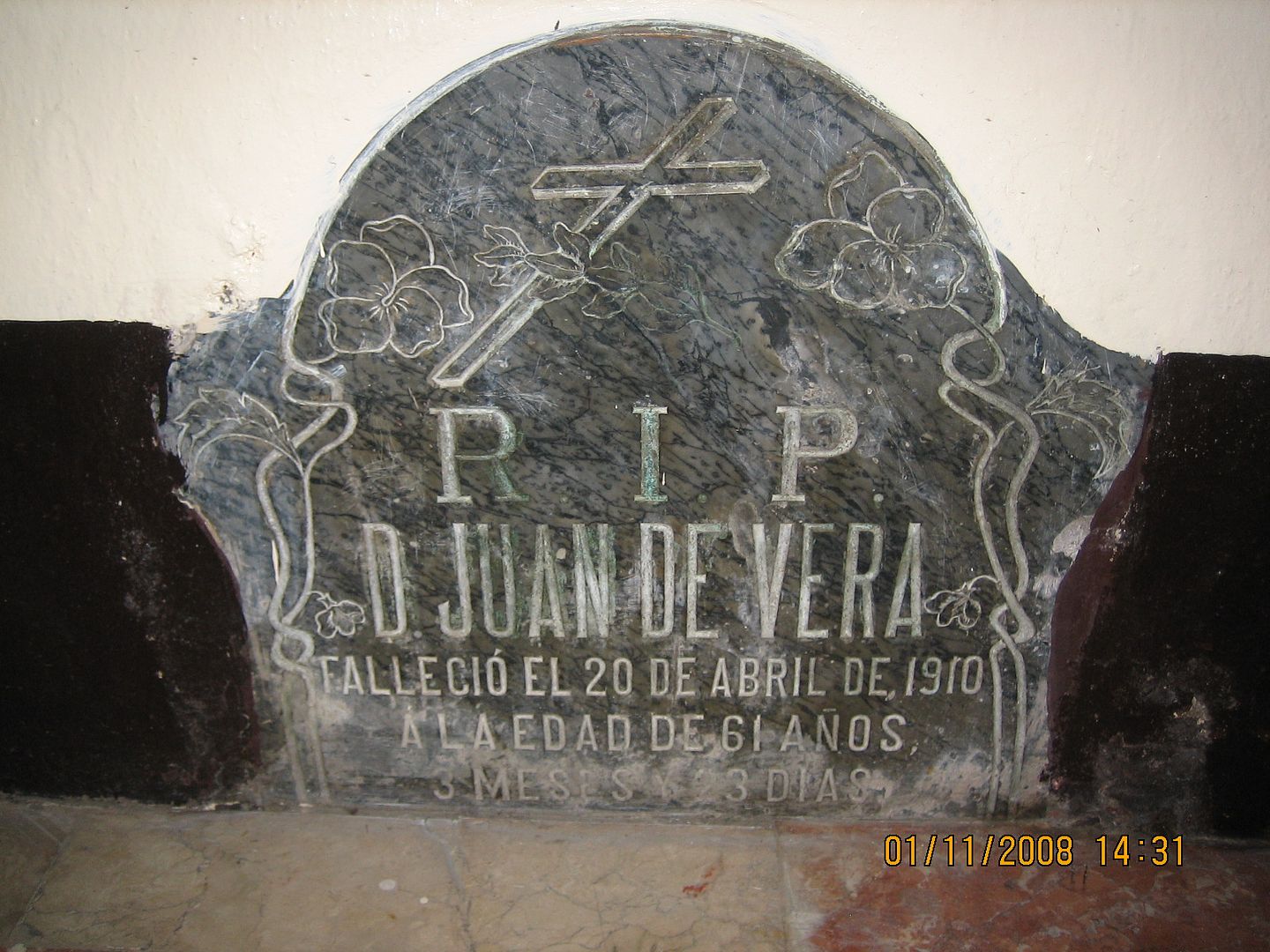

Next up is a weirdly-shaped gray marble marker for Don Juan de Vera, who died on 20 April 1910 at the precise age (again) of 61 years, 3 months, and 23 days.

Then we have a shared tombstone for Nemecia V. dela Fuente (19 December 1858 – 28 June 1917) and Pedro F. de los Reyes, whose details have themselves been buried, as might have been any clues to the nature of their relationship. As it is, it’s just intriguing. Hmmm….

Don Isidoro Chico died on the 3rd of June sometime in the 19th century (the year of 18_9 is unclear due to the bad state of the gray marble), presumably unmarried and childless as the only ones who signify their remembrance are his siblings.

On the left side of the church, beginning from the left-side altar, are several more tombstones. Here is a floral-and-vine-decorated one for Don Mariano Villarca, who died on 14 June 1898 at the age of 55 years, two months (“dalauang buan”), and three days.

A pair of markers are placed beside each other nearby – on the left is one for “Victorina V. Bernabe at Navarro” who died on 27 July 1893 and whose age is difficult to read behind the grime, and on the right is one for what might be her sister or other female relative named Catalina whose details are covered by the wooden urna for the processional Marian image we saw earlier.

Another unfortunate “twice-buried” individual comes next.

Here is a beautifully-designed Art-Nouveau tombstone, whose authentically rendered typeface (as well as lack of polish and partial submergence) makes it rather difficult to read now. As far as I can make out, it is for Don Antero Qiambao.

An upright marker for Cristina Veola (probably a variant spelling of the more common "Viola") is next. She died on 11 April 1916, and the remembrance is (solely) from her daughter Filomena de Villaroman. (I wonder what her other children thought about that!)

Some more stylized gumamelas feature on the tombstone of Casimira V. Mendoza, who died at the relatively advanced age (in this community anyway) of 87 years on 15 December 1923.

Another differently-designed marker is for Escolastica de la Fuente, who died on 8 March 1916 at the age of 52 years, 1 month, and 4 days.

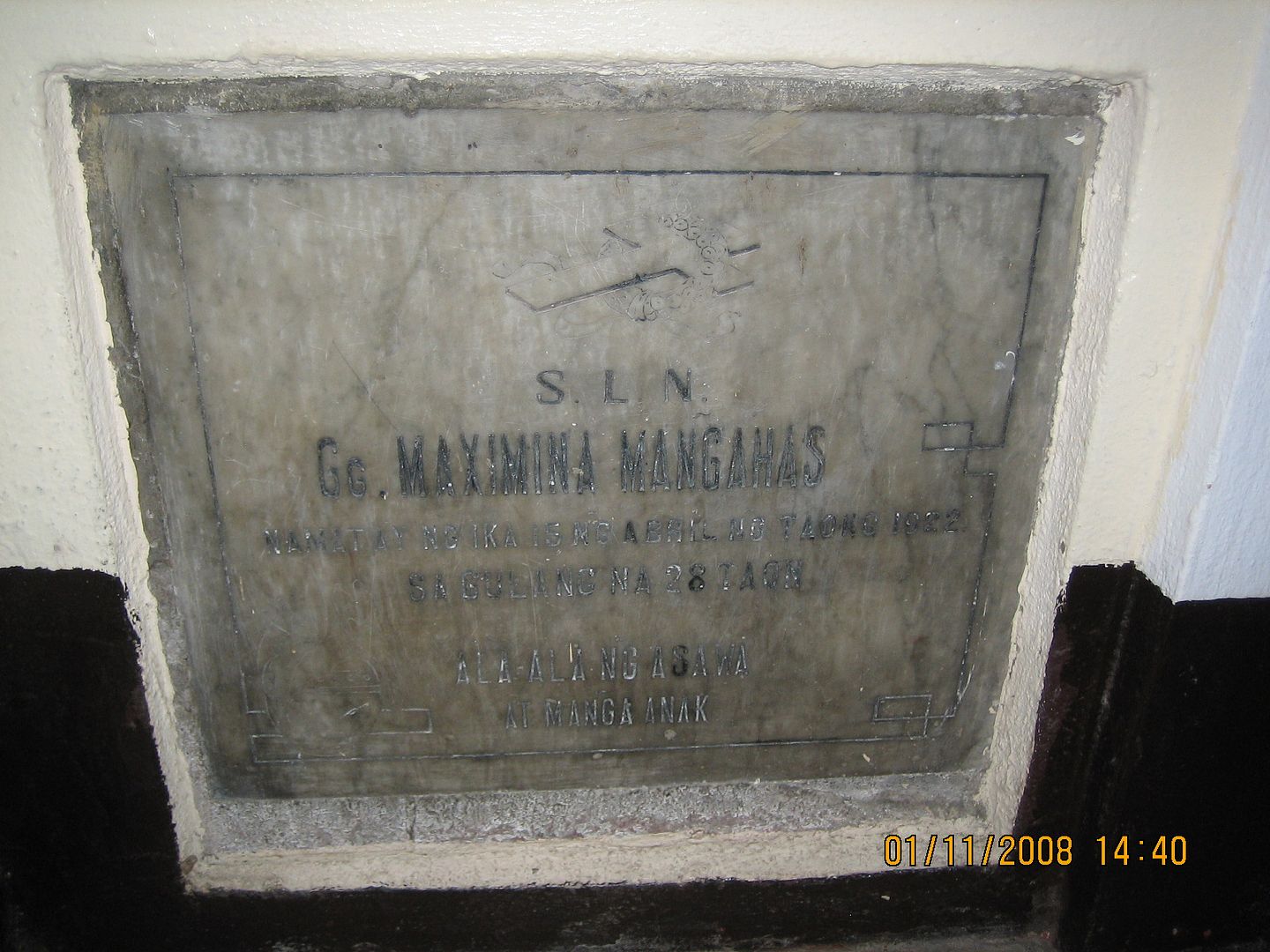

Then there’s Maximina Mangahas, who died on 15 April 1922 at a young 28 years.

A flamboyant cross-shaped design is reserved for the tombstone of Julian Valte Mangahas, 1855-1907, whose wife and kids don’t care to give us his age precisely.

And another weirdly-shaped marker had been commissioned for the octogenarian Teodoro Lopez, who died on 14 September 1914, at the age of 86.

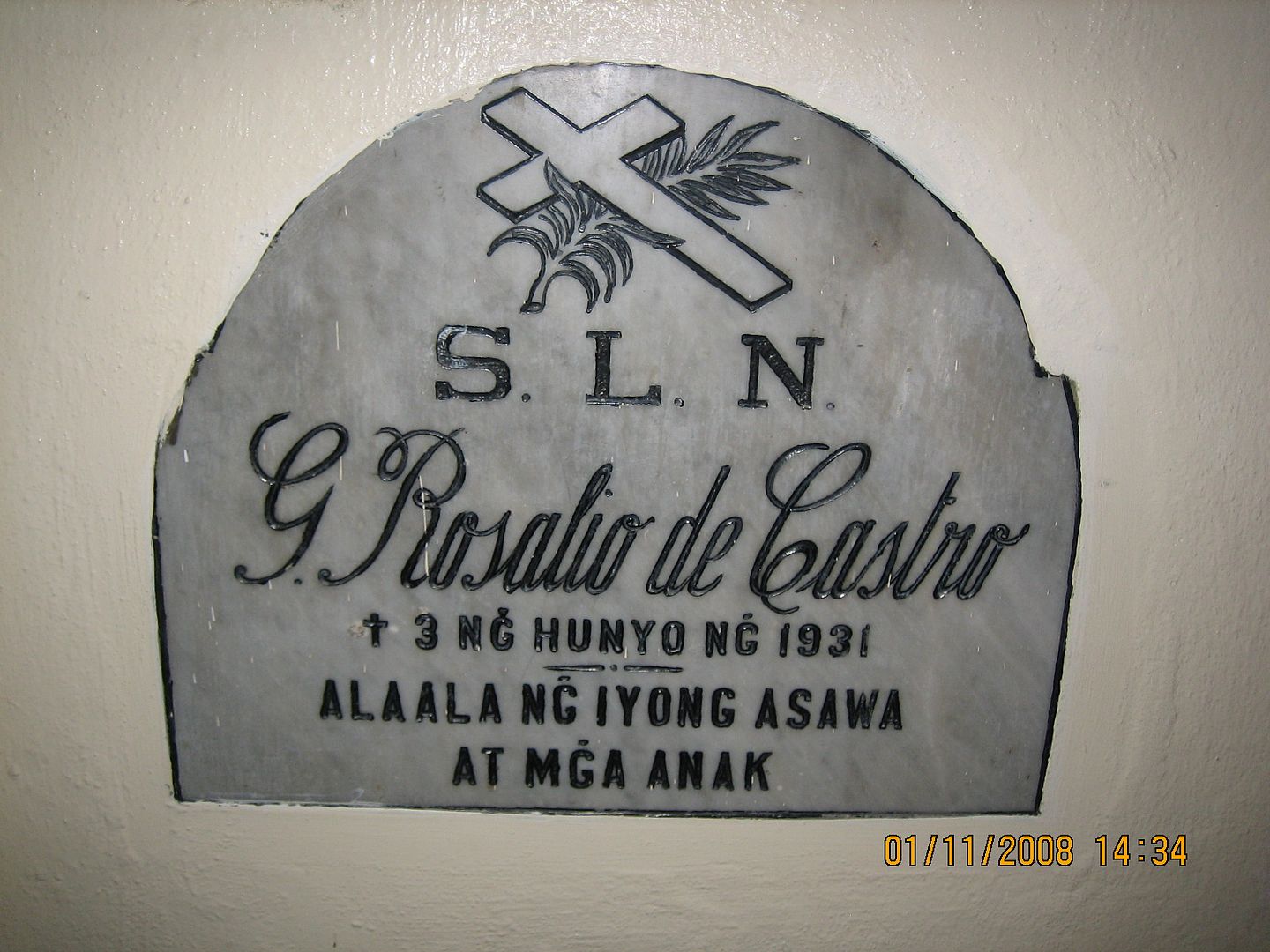

Even inside the sacristy with the large antique crucifix and vestry cabinet that we visited earlier, there are quite a number of tombstones, starting with Rosalio de Castro, who died on 3 June 1931.

Then Romana Villarka, 9 November 1928, 39 years and two months.

This overly leafy gray marker is for Miguel Mendoza Perez, 29 September 1867 – 6 January 1931, at 63 years. Touchingly, it is dedicated as “Ala-ala ng Namimighating Asawa at Anak.”

Here is an extremely legible tombstone, thanks to the large sans serif bold typeface and deeply-incised letters. We therefore have no doubt that it is for Francisca de Vera de Mendoza, who died on 5 November 1921, and that the memorial was from her daughter and grandchildren, who implore us to “Pray for Her!”

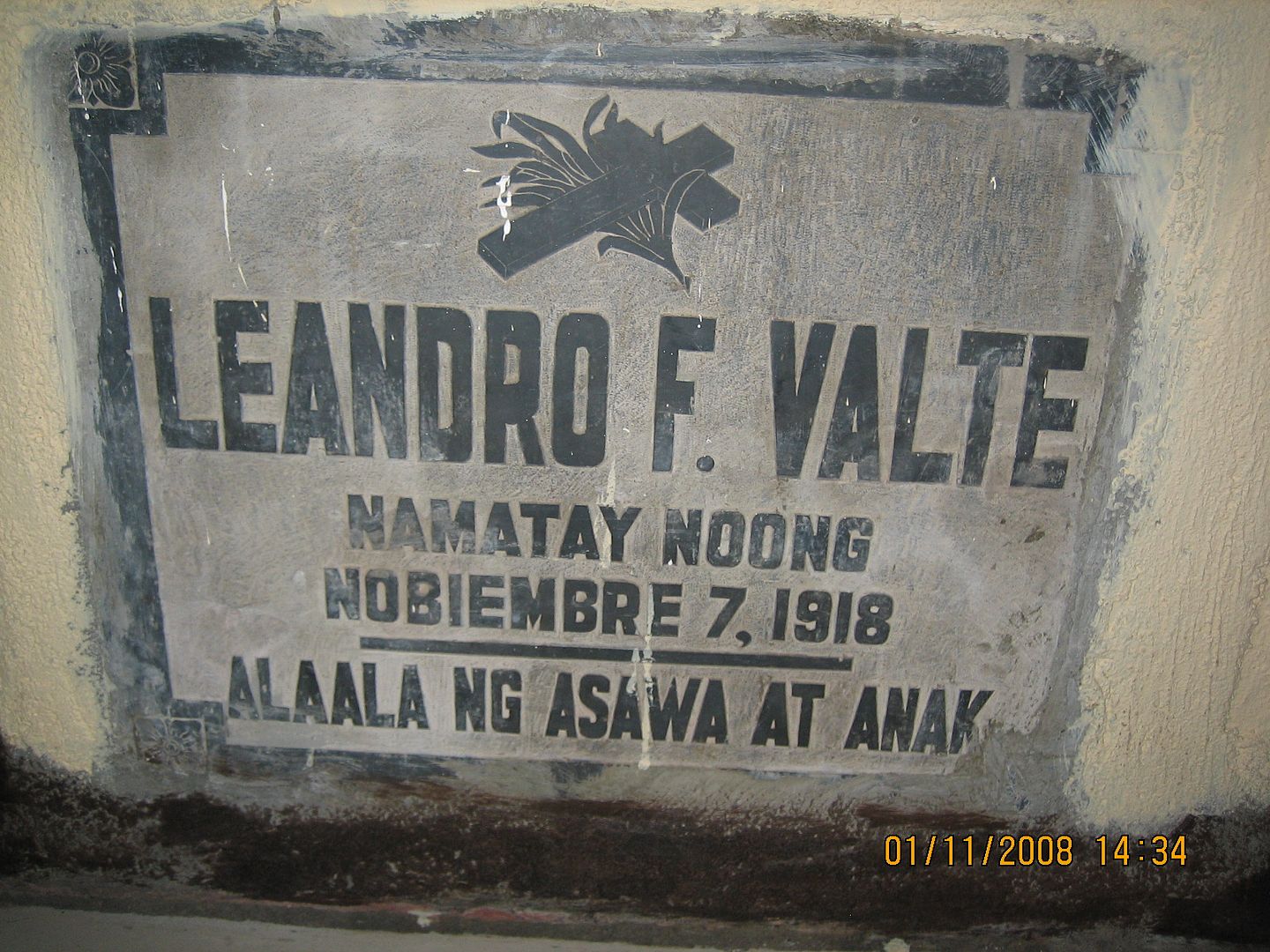

Another legible marker is this one for Leandro F. Valte, who died 7 November 1918, age not indicated.

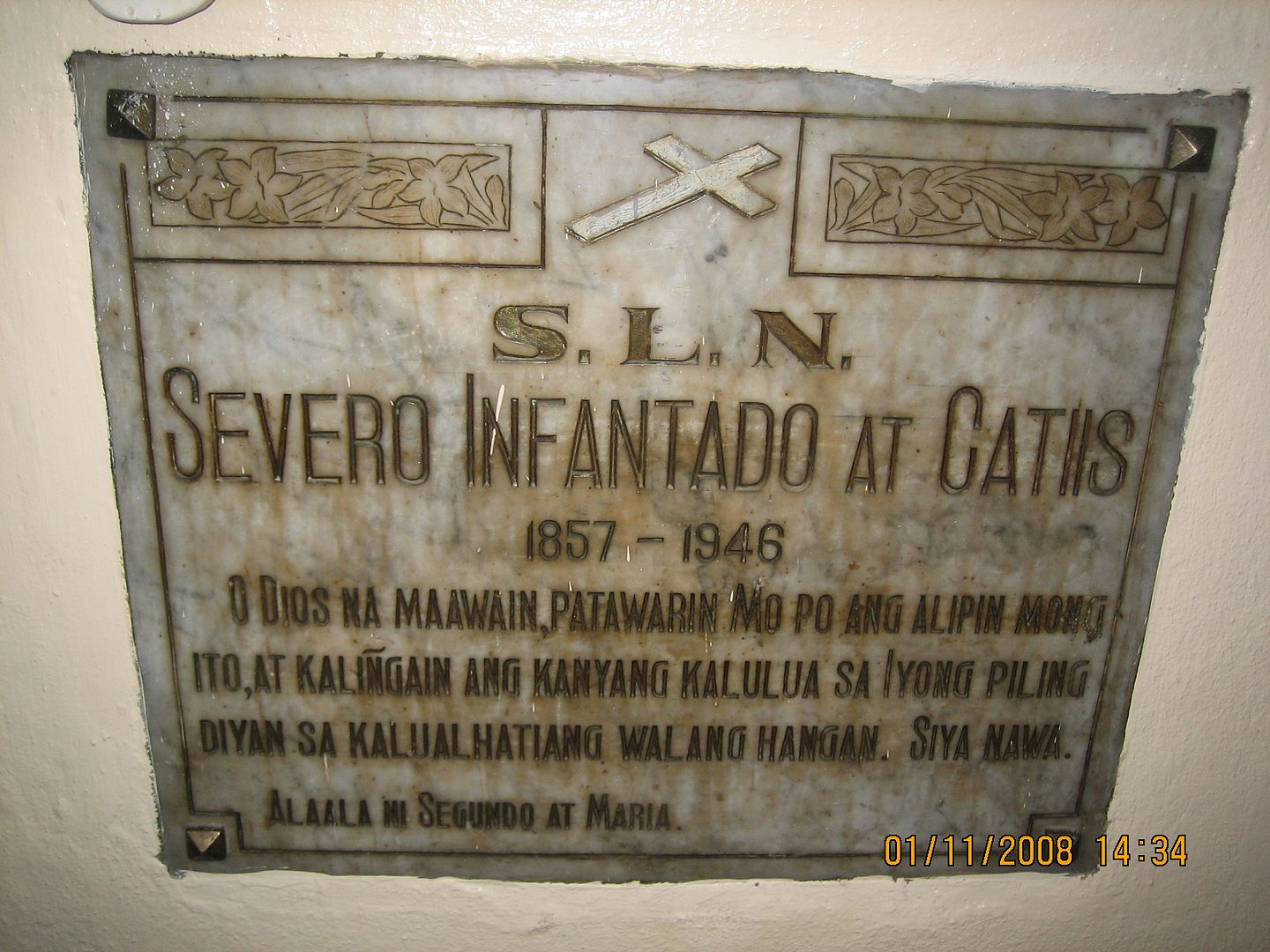

The tombstone for Severo Infantado Catiis (1857-1946) has its incisions handsomely painted in gold. This is put to good use in a hearfelt prayer that “Segundo at Maria,” presumably his children, have included: “O Dios na maawain, patawarin mo po ang alipin mong ito, at kalingain ang kanyang kalulua sa Iyong piling diyan sa kalualhatiang walang hangan. Siya nawa.”

The last marker in this sacristy is a small but very nicely sculpted one for Modesta Papa de Galvez, 1896-1928.

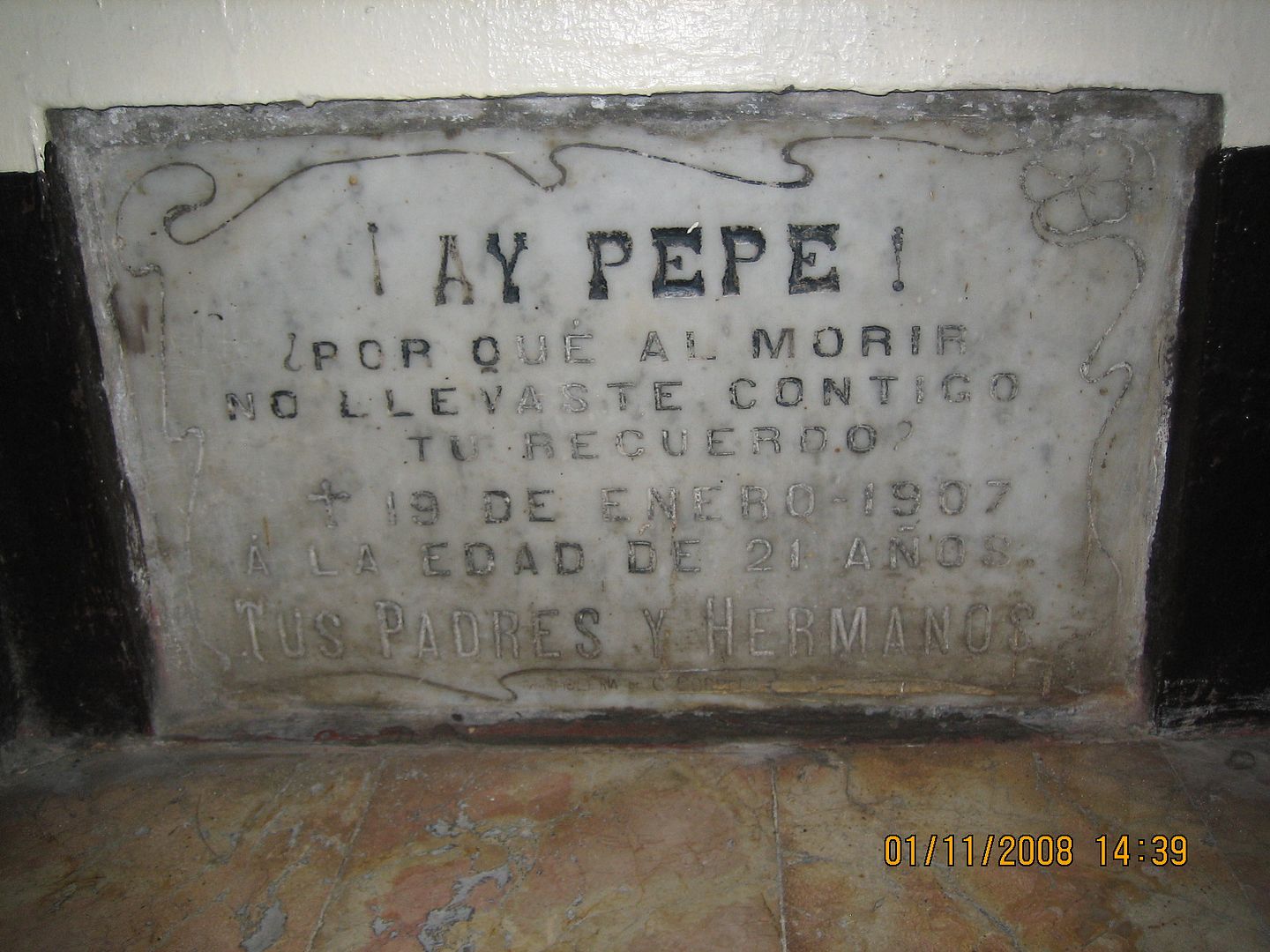

Back outside in the nave, on the left side wall, has got to be the most touching of all the tombstones in this church. Its dedicatee is a young man, just twenty-one years old when he died on 19 January 1907. The deceased’s full name is not even specified, but given that “Pepe” is the standard nickname for “Jose,” that just might be his given name. Yet his family name remains unknown to us.

Loosely translated, it reads, “Oh Pepe! When you died, why did you not take with you our memories of you?” Such a poetic way of expressing the profound grief of his obviously greatly bereaved parents and siblings.

Most of the tombstones in this church were unfortunately uncleaned and likely unremembered even on this All Saints’ Day. Given the near-century that most of them have been here, it is possible that their present-day relatives, if any, don’t even know they exist.

The few that are still remembered are therefore noteworthy, as with this last one, near the main entrance on the right side. The deceased is Bartolome Mendoza Fernandez, who died on 17 September 1908 at the age of 45 years.

One hundred years later, his presumed descendants still remember him with flowers and a candle.

Will we be as blessed, a hundred years after we too pass away?

Originally published on 20 November 2008. All text and photos copyright ©2008 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

No comments:

Post a Comment