My family’s pretty devout, Roman Catholically-speaking. Not only do several of our members hear daily Mass, we also serve as lectors and commentators, and we’re also active in church organizations. And importantly, we like joining processions.

Even when I was in short pants as a little schoolboy, I would walk hand-in-hand with my grandfather in Holy Week processions in Barasoain, Malolos. A few years before Lolo died in 1980, my regular procession mate became my father. After he himself died in 1986, my mother, aunts, and brother became members of the regular procession gang, in various permutations each year.

Throughout all those years, the common family plaint was, “If only we had our own processional image and carroza.” To which an eavesdropper might justifiably respond, “Well, why not?” And if one listened for a reaction, one would hear mumbles, perhaps a stray, “They’re too costly; we still need to raise funds.” Or some similar theme.

One would think that after several decades of this mumbling and grumbling, some modest progress might be made. In the summer of 2002, I came back home after some years of studying and working and living abroad, and I realized that absolutely no progress had been made in the three decades on this front since I first marched my first Holy Week procession. I figured that the time was overripe to rectify this situation.

Even when I was in short pants as a little schoolboy, I would walk hand-in-hand with my grandfather in Holy Week processions in Barasoain, Malolos. A few years before Lolo died in 1980, my regular procession mate became my father. After he himself died in 1986, my mother, aunts, and brother became members of the regular procession gang, in various permutations each year.

Throughout all those years, the common family plaint was, “If only we had our own processional image and carroza.” To which an eavesdropper might justifiably respond, “Well, why not?” And if one listened for a reaction, one would hear mumbles, perhaps a stray, “They’re too costly; we still need to raise funds.” Or some similar theme.

One would think that after several decades of this mumbling and grumbling, some modest progress might be made. In the summer of 2002, I came back home after some years of studying and working and living abroad, and I realized that absolutely no progress had been made in the three decades on this front since I first marched my first Holy Week procession. I figured that the time was overripe to rectify this situation.

In the course of the following months, I first focused on getting settled in a new job, purchasing an apartment in the city, and attending to other logistical necessities incidental to my professional and family situation in the Philippines. While doing all those, I started to inquire whenever and wherever I could about possible resources for commissioning Holy Week processional images and the carrozas on which they would have to be mounted.

Endorsements and Recommendations. I spoke to antique dealers, many of whom also dealt in religious images. One respected Manila dealer was most helpful, and gave me a couple of leads. She however had one strong recommendation.

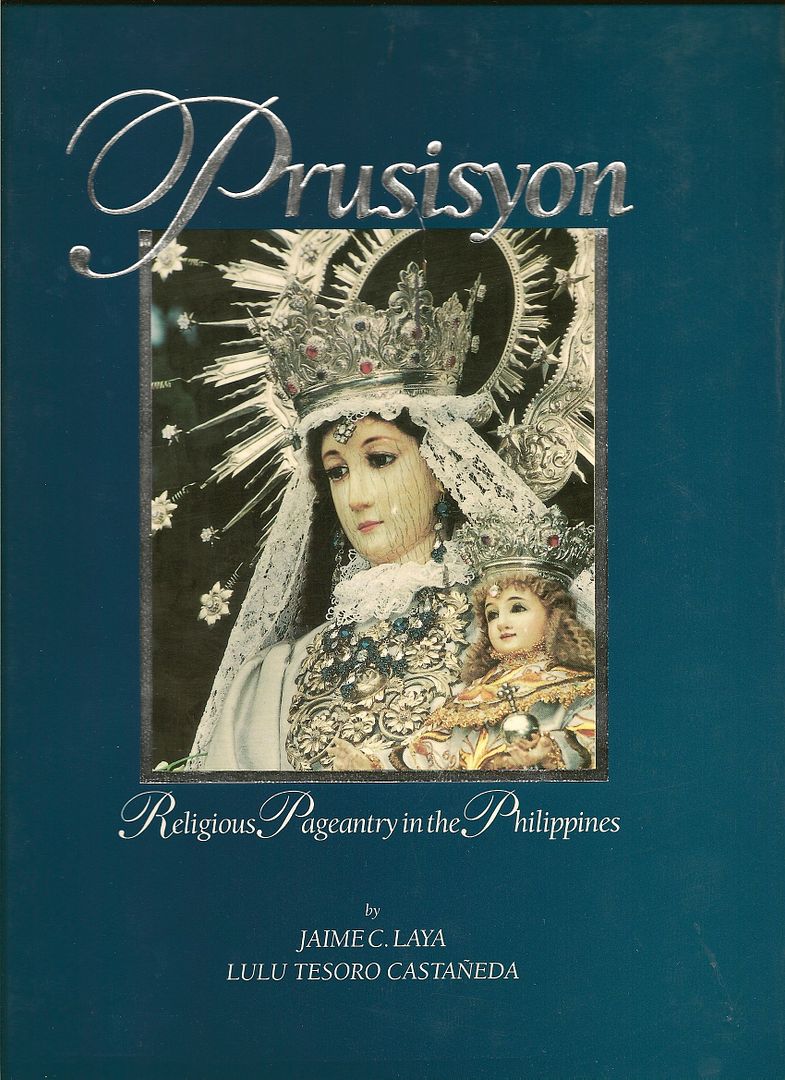

I leafed through books in our family library in case I might find leads there. One of these books was “Prusisyon: Religious Pageantry in the Philippines” by Jaime C. Laya and Lulu Tesoro Castañeda.

I tried to get in touch with Dr. Laya through his well-known and respected public accounting and consulting firm in Makati, managing to send him an email message via his office email address. I was slightly surprised that he had actually taken the time to respond to me, and had given me a clear and equivocal recommendation as to how to proceed with our family project.

And I searched online. I stumbled upon an article published in the Sun-Star Pampanga, entitled “And all the Angels and Saints: Our Santo Tradition,” written by a certain Alex Castro, who I presumed was a staff reporter for that newspaper. There was an email address supplied at the end of the article, so I wrote to him and explained our undertaking. He replied, and he too had an unequivocal recommendation as to what our next step ought to be.

Interestingly, all three of them – the respected antique dealer, Dr. Laya, and Mr. Castro – all gave the same exact recommendation. And that was that we should go to the processional santo collector and maker, Mr. Francisco Vecin, who, as it turns out, was located not very far from our home base in the city, in Makati.

All three recommenders had given me Mr. Vecin’s phone number, so there were no longer any excuses to delay – I phoned him, and asked for directions to his place. After circling the block several times and phoning him from my mobile phone to confess that I was lost, I eventually found his address – a nondescript, extremely anonymous shopfront totally dwarfed and drowned out by the neighbors.

This was just a few weeks before Holy Week 2003, and as might be expected, Mr. Vecin’s workshop was teeming with activity. Frantic was more like it. He and his team of craftsmen and artists were rushing to complete a near-lifesized Last Supper processional tableau for a family in Cavite. He tells me that this was ordered only the previous Christmas, and as if to impress upon me that there was no chance he could make anything for us for that same Holy Week, clarifies that he usually requires an order lead time of about one year.

I hasten to confirm that indeed, we’re not expecting to have something procession-ready from nothing in just a few weeks. It turns out that as far as his first-time callers go, we are in a distinct minority, as most other people who inquire expect that something can be taken out of inventory, dusted off, and delivered within a few days. Privately, I figure, we had been waiting several decades, what’s another year?

Mr. Vecin and I agree to meet up again a week or two after Holy Week. In the intervening period, I was to more clearly define our specifications, including, obviously, what processional image my family wanted to commission from him exactly. Only with that could he give us a firm quote, with a target delivery in time for Holy Week 2004.

Fastidious and Fussy. In the meantime, for that Holy Week of 2003, and to set some baseline for our prospective specifications for when I was to meet up with Mr. Vecin again, I had enlisted my brother in some fieldwork to assess the state of Holy Week processions and processional images in the Philippines. We revisited Barasoain Church and the Malolos Cathedral, and went to Baliwag for the first time.

We also dropped by Santa Isabel in Malolos, and checked in on the new Quasi-Parish in Violeta Village, Guiguinto, where our aunts lived. For this was our family’s likely foot-in-the-door into the world of processional images, since they were only in the early stages of putting together their Holy Week processional line-up there.

In quick order, my brother and I enthusiastically informed our aunts that we would be targeting to join the Holy Week procession in their new Quasi-Parish, and all they had to do was decide what image to participate with. Since we obviously were newbies at this sort of thing, we set the limit at just one solitary image. Perusing the printed line-up in the parish newsletter, we discovered that both Saint Peter and Saint John the Evangelist, the likely male solitary images, were already accounted for, so we would probably have to choose one of the Holy Women instead.

And what fortune, since of all the Holy Women, it turned out that Saint Martha had not yet been spoken for.

Saint Martha, of course, was the fastidious lady friend of our Lord, who preoccupied herself with cooking and other housekeeping duties, while her presumably more pious sister Mary preferred to sit at the Lord’s feet and listen to His teaching. The two sisters are often held up as archetypes of the two strains of devotional life – the “active” (Martha), and the “contemplative” (Mary). Saint Martha as a consequence had been designated patron of housekeepers and business people. And since we in our family are nothing but a bunch of fussy housekeepers and pernickety business people, we probably deserve someone like Saint Martha to be our patron saint.

So that’s how we selected Saint Martha to be our family-sponsored future processional image in the Quasi-Parish of the Holy Family in Violeta Village, Guiguinto, Bulacan. Therefore, shortly after that Holy Week in 2003, our aunts submitted a registration (“reservation”) for our prospective Saint Martha processional image’s participation in the Holy Week processional line-up, to the parish office. Which meant that we had a bit less than a year to get out act together.

Field Research. It was then time for my brother and me to review the results of our assessment of the state of processions in the general area. Our visits to Malolos Cathedral and Santa Isabel Church were not very productive, as we remembered that hardly any processional images could be parked inside these church buildings, which meant that our samples were scant and not so desirable, and did not include any images of Saint Martha.

On the other hand, our first ever Holy Week visit to Baliwag on Holy Wednesday 2003 was quite eye-opening, though perhaps not for the best of reasons. Whereas we even walked the entire processional route (all several kilometers and hours of them around the Baliwag town center), our enthusiasm was dampened by the sight of images such as this vaguely 16th century English-cum-17th century Spanish-looking Santa Marta:

Endorsements and Recommendations. I spoke to antique dealers, many of whom also dealt in religious images. One respected Manila dealer was most helpful, and gave me a couple of leads. She however had one strong recommendation.

I leafed through books in our family library in case I might find leads there. One of these books was “Prusisyon: Religious Pageantry in the Philippines” by Jaime C. Laya and Lulu Tesoro Castañeda.

I tried to get in touch with Dr. Laya through his well-known and respected public accounting and consulting firm in Makati, managing to send him an email message via his office email address. I was slightly surprised that he had actually taken the time to respond to me, and had given me a clear and equivocal recommendation as to how to proceed with our family project.

And I searched online. I stumbled upon an article published in the Sun-Star Pampanga, entitled “And all the Angels and Saints: Our Santo Tradition,” written by a certain Alex Castro, who I presumed was a staff reporter for that newspaper. There was an email address supplied at the end of the article, so I wrote to him and explained our undertaking. He replied, and he too had an unequivocal recommendation as to what our next step ought to be.

Interestingly, all three of them – the respected antique dealer, Dr. Laya, and Mr. Castro – all gave the same exact recommendation. And that was that we should go to the processional santo collector and maker, Mr. Francisco Vecin, who, as it turns out, was located not very far from our home base in the city, in Makati.

All three recommenders had given me Mr. Vecin’s phone number, so there were no longer any excuses to delay – I phoned him, and asked for directions to his place. After circling the block several times and phoning him from my mobile phone to confess that I was lost, I eventually found his address – a nondescript, extremely anonymous shopfront totally dwarfed and drowned out by the neighbors.

This was just a few weeks before Holy Week 2003, and as might be expected, Mr. Vecin’s workshop was teeming with activity. Frantic was more like it. He and his team of craftsmen and artists were rushing to complete a near-lifesized Last Supper processional tableau for a family in Cavite. He tells me that this was ordered only the previous Christmas, and as if to impress upon me that there was no chance he could make anything for us for that same Holy Week, clarifies that he usually requires an order lead time of about one year.

I hasten to confirm that indeed, we’re not expecting to have something procession-ready from nothing in just a few weeks. It turns out that as far as his first-time callers go, we are in a distinct minority, as most other people who inquire expect that something can be taken out of inventory, dusted off, and delivered within a few days. Privately, I figure, we had been waiting several decades, what’s another year?

Mr. Vecin and I agree to meet up again a week or two after Holy Week. In the intervening period, I was to more clearly define our specifications, including, obviously, what processional image my family wanted to commission from him exactly. Only with that could he give us a firm quote, with a target delivery in time for Holy Week 2004.

Fastidious and Fussy. In the meantime, for that Holy Week of 2003, and to set some baseline for our prospective specifications for when I was to meet up with Mr. Vecin again, I had enlisted my brother in some fieldwork to assess the state of Holy Week processions and processional images in the Philippines. We revisited Barasoain Church and the Malolos Cathedral, and went to Baliwag for the first time.

We also dropped by Santa Isabel in Malolos, and checked in on the new Quasi-Parish in Violeta Village, Guiguinto, where our aunts lived. For this was our family’s likely foot-in-the-door into the world of processional images, since they were only in the early stages of putting together their Holy Week processional line-up there.

In quick order, my brother and I enthusiastically informed our aunts that we would be targeting to join the Holy Week procession in their new Quasi-Parish, and all they had to do was decide what image to participate with. Since we obviously were newbies at this sort of thing, we set the limit at just one solitary image. Perusing the printed line-up in the parish newsletter, we discovered that both Saint Peter and Saint John the Evangelist, the likely male solitary images, were already accounted for, so we would probably have to choose one of the Holy Women instead.

And what fortune, since of all the Holy Women, it turned out that Saint Martha had not yet been spoken for.

Saint Martha, of course, was the fastidious lady friend of our Lord, who preoccupied herself with cooking and other housekeeping duties, while her presumably more pious sister Mary preferred to sit at the Lord’s feet and listen to His teaching. The two sisters are often held up as archetypes of the two strains of devotional life – the “active” (Martha), and the “contemplative” (Mary). Saint Martha as a consequence had been designated patron of housekeepers and business people. And since we in our family are nothing but a bunch of fussy housekeepers and pernickety business people, we probably deserve someone like Saint Martha to be our patron saint.

So that’s how we selected Saint Martha to be our family-sponsored future processional image in the Quasi-Parish of the Holy Family in Violeta Village, Guiguinto, Bulacan. Therefore, shortly after that Holy Week in 2003, our aunts submitted a registration (“reservation”) for our prospective Saint Martha processional image’s participation in the Holy Week processional line-up, to the parish office. Which meant that we had a bit less than a year to get out act together.

Field Research. It was then time for my brother and me to review the results of our assessment of the state of processions in the general area. Our visits to Malolos Cathedral and Santa Isabel Church were not very productive, as we remembered that hardly any processional images could be parked inside these church buildings, which meant that our samples were scant and not so desirable, and did not include any images of Saint Martha.

On the other hand, our first ever Holy Week visit to Baliwag on Holy Wednesday 2003 was quite eye-opening, though perhaps not for the best of reasons. Whereas we even walked the entire processional route (all several kilometers and hours of them around the Baliwag town center), our enthusiasm was dampened by the sight of images such as this vaguely 16th century English-cum-17th century Spanish-looking Santa Marta:

Well, at least, we knew how we did not want OUR Saint Martha to look like.

Back home in more familiar territory in Barasoain on Good Friday 2003, my brother and I looked around the well-filled church (this being that rare place where nearly the entire processional line-up is parked inside throughout Holy Week) and reacquainted ourselves with the favorite images of our youth. And we very soon zoomed in on beautiful Saint Martha, holding her traditional palm branch and tray of bread, and with a large key slung from her waistband.

Back home in more familiar territory in Barasoain on Good Friday 2003, my brother and I looked around the well-filled church (this being that rare place where nearly the entire processional line-up is parked inside throughout Holy Week) and reacquainted ourselves with the favorite images of our youth. And we very soon zoomed in on beautiful Saint Martha, holding her traditional palm branch and tray of bread, and with a large key slung from her waistband.

We even shot her in profile, allowing her to show off her pink robe and silvery cape.

We also admired the delicate chrome-plated metal appliqués on her carroza

and, in keeping with the pink color scheme, its pink flowers, pink skirt, and even the pink-tinged spherical lamp glass fixtures.

We took note of the owners' home on the label on the carrozza, in the hope that we could establish contact with them in the future to seek their advice as well. But based on what we had seen, we felt that this Barasoain Santa Marta was a fairly lofty benchmark on which to base our own prospective processional image on. So far, so good.

After the usual excitement of Holy Week and the winding down of devotional activities beginning Easter Monday, we resumed our deep thinking and careful contemplation of what specifications to convey to Mr. Vecin in just a couple of weeks. Returning to Dr. Laya’s “Prusisyon” book, our attention was called by a full-page antique sepia photo of a processional image.

This was a life-sized image of Saint Veronica, owned by the Hidalgo family of Quiapo, and photographed circa 1900, ready to run for a turn-of the-century Holy Week procession. We admired her simple yet elegant garments, notably a headdress and a cape draped over one shoulder. We imagined that this image could be easily transformed into a Saint Martha if her thrice-printed veil were replaced with a tray of bread and a palm leaf. We quickly decided that this was the target look of our Saint Martha, and I resolved to inform Mr. Vecin so.

Back to Vecin’s. Soon enough, I was back at the Vecin Workshop, with clear photographs of the Barasoain Santa Marta as well as a scanned page-sized print-out of the Quiapo Veronica. Mr. Vecin examined these illustrations carefully, and appeared pleased with what he saw. He remarked that Barasoain’s Santa Marta looked very beautiful indeed, and in fact that it looked vaguely familiar.

On the other hand, Mr. Vecin admired the by-then familiar antique photo of the Veronica from the Prusisyon book, and said that although that style of garb was currently more frequently specified for the Samaritan Woman and other minor female characters in Holy Week tableaux, there was of course no reason to withhold it from a simple and hardworking Holy Woman such as Saint Martha was. He then added that he liked the fact that we had chosen to lean on the side of simplicity, rather than the more common tendency to specify the most ostentatious accoutrements that budgets could accommodate (or not).

With that, Mr. Vecin said that he felt that he had enough information to prepare a quotation for us, which he would convey to me by telephone in due course.

As I prepared to leave, I mentioned to Mr. Vecin that even if we managed to come to an agreement on the production of the Saint Martha image, my family and I still had to look for a carroza for it. He said that there were many carroza makers around, and that I should check them out, but if I needed more specific help, I could phone him any time.

Other Neighborhoods and Territories. While waiting for Mr. Vecin’s quote, I figured that there was no harm in checking out other leads. The antique dealer who had also recommended Mr. Vecin had also mentioned a santo-making workshop in the city of Manila. I dutifully visited it one morning to check it out.

I discovered that this workshop specialized in making images of ivory, and they offered to make us a life-sized Saint Martha, with head and hands of ivory on a wooden mannequin body. The quote for this, which was immediately available right then and there, was impressive, and would have been sufficient to purchase a brand-new car. The proprietress and her craftsmen were pleasant, but because we were not scheduled to purchase any motor vehicles that year, much less processional images priced equivalently, I thanked them for their hospitality and went back to minding my usual, non-anxiety-inducing, affairs.

I figured that my time was better spent pursuing other leads. At that time, there was a religious supplies store on the ground floor of Park Square 2 in Ayala Center (as of this writing already torn down to make way for a new hotel). I had frequently window-shopped here, and occasionally actual-shopped (not for windows but for small items like stampitas and rosaries). Their medium- and larger-sized religious images were satisfactory-looking, if not very consistently so. Nonetheless, I asked the sales attendant for the address of their workshop, which was in another part of the city. Soon enough, I managed to visit them there, and saw their processional images in production.

What interested me more was that the proprietor mentioned that they also manufactured carrozas. In fact, he said that I could examine some actual examples not far from there – actually around the corner in the neighborhood Aglipayan Chapel (the proprietor and his family were devout Aglipayans). So I did, and regretted not having a camera with me (an admittedly rare occasion), because if I had, I would have been able to take photos of their most interesting all-fiberglass carrozas (a square one, and a slightly longer rectangular one), molded to resemble the more usual wood-carved specimens around.

These carrozas were painted, rather than varnished, as that obviously concealed its fiberglass nature better. These also had pneumatic motor vehicle tires instead of the more traditional solid wooden wheels, and a wide-pivoting steering handle that the proprietor proudly said caused his carrozas to have the smallest turning circle possible, useful in processional routes with narrow streets and tight corners. His final claim was that he and his people were then trying to figure out how to engineer a hand-braking system from the steering handle in front, similar to how bicycles were braked.

I was impressed with their ingenuity and resourcefulness – molded fiberglass bodies, small turning circles, handbrakes – but unfortunately less so with the aesthetics, authenticity, and elegance (or lack thereof) of their carrozas. Nonetheless, I asked for, and promptly received, a quote for both a five-foot female processional image and a matching carroza, and slipped it into my thickening binder file.

Impressed, Hammered, and Fleeced. There was another religious supplies shop in another, somewhat more swanky, part of Ayala Center. Their religious images were decorated to dazzle (lots of gold and silver paint and gemstones), as presumably this was what appealed to their target market.

I inquired about the possibility of commissioning a life-sized Saint Martha with a matching carroza. Within seconds, the proprietress whipped out photographs of an actual processional Saint Martha trampling upon an alligator and mounted on a low but well-proportioned wooden carroza. She said that they had in fact recently completed this ensemble for a parish in another part of the city, and could easily make the same for my family and me.

Naturally, I asked for a quote, which was whipped out in barely less time as the photos. The price of the image was expectedly grand, and the price of the carroza was about the same as that of the life-sized ivory image that the earlier workshop had quoted me for. Clearly, I was in uncomfortable territory here.

Mr. Castro had given me a lead on carrozas—a prolific Pampanga carroza maker whom he knew personally. I asked if this maker could come to the city to meet me in my office. One rainy morning, he came, huffing and puffing from the lengthy road trip, and rolled out on my office table his meticulously drawn designs for a carroza for a solitary processional image.

These were sufficiently impressive, it must be said, and reflected this maker’s professional background as a furniture maker in the “Betis” Neo-Baroque style. When the time came for him to give me his quote, he sheepishly pronounced the monetary amount, his eyes shifting uncomfortably. As they indeed should have, since his quote was stratospheric. Why go for a distant maker like this guy, when I could be fleeced from closer proximity, I thought to myself.

I should have been careful what I asked for, since not long after that, I received a call from someone who presented himself as a maker and restorer of carrozas. He said that he specialized in silver-plated hammered-brass carroza bodies, and had restored numerous antique examples of that type, including those in museums (e.g., the San Agustin Museum). He could of course make new ones to order, and offered to visit my office at my convenience so that he could show me samples of his work.

In a few days, there he was, sitting in my office, and strongly smelling of cigarette smoke, but otherwise decent-looking enough. He had a million stories to tell, including how he had been a regular service provider to the kindly friars of the San Agustin Museum, as well as how he was a personal acquaintance of Mr. Vecin.

He came with impressive samples of his hammered-brass work, which he said would be typical of the material that he would use to create an all-brass silver-plated carroza for our Saint Martha. He added that, knowing Mr. Vecin’s usual style, he was certain that Mr. Vecin's image would be impressive and that his carroza would complement it even more impressively.

He offered to leave his hammered-brass samples with me, so that I could show them to my family, in the expectation that they would agree that his proposal was the one to be favored. The only thing missing of course was the price, and he was ready for that too. Unsurprisingly, it was impressive. It was the most expensive carroza price that I had received till then, and since.

Nonetheless, I took him up on his offer for me take home his brass samples. My family was impressed with them, but I decided to spare them the shock (or mirth) that would potentially result from their knowledge of the corresponding price tag.

I also showed these brass samples to Mr. Vecin on a subsequent visit, who too was impressed with them. He wasn’t so impressed, however, when I told him that the gentleman mentioned that they were each other's acquaintances – he said that he had never heard of that man's name nor did he remember meeting anyone who matched my description of him. I can’t say that I was all that surprised. I arranged to have this hammered-brass guy retrieve his samples from my office at his earliest convenience. And thanked my proverbial lucky stars for me having escaped from being hammered, or fleeced, or both.

Back to Vecin’s. Soon enough, I was back at the Vecin Workshop, with clear photographs of the Barasoain Santa Marta as well as a scanned page-sized print-out of the Quiapo Veronica. Mr. Vecin examined these illustrations carefully, and appeared pleased with what he saw. He remarked that Barasoain’s Santa Marta looked very beautiful indeed, and in fact that it looked vaguely familiar.

On the other hand, Mr. Vecin admired the by-then familiar antique photo of the Veronica from the Prusisyon book, and said that although that style of garb was currently more frequently specified for the Samaritan Woman and other minor female characters in Holy Week tableaux, there was of course no reason to withhold it from a simple and hardworking Holy Woman such as Saint Martha was. He then added that he liked the fact that we had chosen to lean on the side of simplicity, rather than the more common tendency to specify the most ostentatious accoutrements that budgets could accommodate (or not).

With that, Mr. Vecin said that he felt that he had enough information to prepare a quotation for us, which he would convey to me by telephone in due course.

As I prepared to leave, I mentioned to Mr. Vecin that even if we managed to come to an agreement on the production of the Saint Martha image, my family and I still had to look for a carroza for it. He said that there were many carroza makers around, and that I should check them out, but if I needed more specific help, I could phone him any time.

Other Neighborhoods and Territories. While waiting for Mr. Vecin’s quote, I figured that there was no harm in checking out other leads. The antique dealer who had also recommended Mr. Vecin had also mentioned a santo-making workshop in the city of Manila. I dutifully visited it one morning to check it out.

I discovered that this workshop specialized in making images of ivory, and they offered to make us a life-sized Saint Martha, with head and hands of ivory on a wooden mannequin body. The quote for this, which was immediately available right then and there, was impressive, and would have been sufficient to purchase a brand-new car. The proprietress and her craftsmen were pleasant, but because we were not scheduled to purchase any motor vehicles that year, much less processional images priced equivalently, I thanked them for their hospitality and went back to minding my usual, non-anxiety-inducing, affairs.

I figured that my time was better spent pursuing other leads. At that time, there was a religious supplies store on the ground floor of Park Square 2 in Ayala Center (as of this writing already torn down to make way for a new hotel). I had frequently window-shopped here, and occasionally actual-shopped (not for windows but for small items like stampitas and rosaries). Their medium- and larger-sized religious images were satisfactory-looking, if not very consistently so. Nonetheless, I asked the sales attendant for the address of their workshop, which was in another part of the city. Soon enough, I managed to visit them there, and saw their processional images in production.

What interested me more was that the proprietor mentioned that they also manufactured carrozas. In fact, he said that I could examine some actual examples not far from there – actually around the corner in the neighborhood Aglipayan Chapel (the proprietor and his family were devout Aglipayans). So I did, and regretted not having a camera with me (an admittedly rare occasion), because if I had, I would have been able to take photos of their most interesting all-fiberglass carrozas (a square one, and a slightly longer rectangular one), molded to resemble the more usual wood-carved specimens around.

These carrozas were painted, rather than varnished, as that obviously concealed its fiberglass nature better. These also had pneumatic motor vehicle tires instead of the more traditional solid wooden wheels, and a wide-pivoting steering handle that the proprietor proudly said caused his carrozas to have the smallest turning circle possible, useful in processional routes with narrow streets and tight corners. His final claim was that he and his people were then trying to figure out how to engineer a hand-braking system from the steering handle in front, similar to how bicycles were braked.

I was impressed with their ingenuity and resourcefulness – molded fiberglass bodies, small turning circles, handbrakes – but unfortunately less so with the aesthetics, authenticity, and elegance (or lack thereof) of their carrozas. Nonetheless, I asked for, and promptly received, a quote for both a five-foot female processional image and a matching carroza, and slipped it into my thickening binder file.

Impressed, Hammered, and Fleeced. There was another religious supplies shop in another, somewhat more swanky, part of Ayala Center. Their religious images were decorated to dazzle (lots of gold and silver paint and gemstones), as presumably this was what appealed to their target market.

I inquired about the possibility of commissioning a life-sized Saint Martha with a matching carroza. Within seconds, the proprietress whipped out photographs of an actual processional Saint Martha trampling upon an alligator and mounted on a low but well-proportioned wooden carroza. She said that they had in fact recently completed this ensemble for a parish in another part of the city, and could easily make the same for my family and me.

Naturally, I asked for a quote, which was whipped out in barely less time as the photos. The price of the image was expectedly grand, and the price of the carroza was about the same as that of the life-sized ivory image that the earlier workshop had quoted me for. Clearly, I was in uncomfortable territory here.

Mr. Castro had given me a lead on carrozas—a prolific Pampanga carroza maker whom he knew personally. I asked if this maker could come to the city to meet me in my office. One rainy morning, he came, huffing and puffing from the lengthy road trip, and rolled out on my office table his meticulously drawn designs for a carroza for a solitary processional image.

These were sufficiently impressive, it must be said, and reflected this maker’s professional background as a furniture maker in the “Betis” Neo-Baroque style. When the time came for him to give me his quote, he sheepishly pronounced the monetary amount, his eyes shifting uncomfortably. As they indeed should have, since his quote was stratospheric. Why go for a distant maker like this guy, when I could be fleeced from closer proximity, I thought to myself.

I should have been careful what I asked for, since not long after that, I received a call from someone who presented himself as a maker and restorer of carrozas. He said that he specialized in silver-plated hammered-brass carroza bodies, and had restored numerous antique examples of that type, including those in museums (e.g., the San Agustin Museum). He could of course make new ones to order, and offered to visit my office at my convenience so that he could show me samples of his work.

In a few days, there he was, sitting in my office, and strongly smelling of cigarette smoke, but otherwise decent-looking enough. He had a million stories to tell, including how he had been a regular service provider to the kindly friars of the San Agustin Museum, as well as how he was a personal acquaintance of Mr. Vecin.

He came with impressive samples of his hammered-brass work, which he said would be typical of the material that he would use to create an all-brass silver-plated carroza for our Saint Martha. He added that, knowing Mr. Vecin’s usual style, he was certain that Mr. Vecin's image would be impressive and that his carroza would complement it even more impressively.

He offered to leave his hammered-brass samples with me, so that I could show them to my family, in the expectation that they would agree that his proposal was the one to be favored. The only thing missing of course was the price, and he was ready for that too. Unsurprisingly, it was impressive. It was the most expensive carroza price that I had received till then, and since.

Nonetheless, I took him up on his offer for me take home his brass samples. My family was impressed with them, but I decided to spare them the shock (or mirth) that would potentially result from their knowledge of the corresponding price tag.

I also showed these brass samples to Mr. Vecin on a subsequent visit, who too was impressed with them. He wasn’t so impressed, however, when I told him that the gentleman mentioned that they were each other's acquaintances – he said that he had never heard of that man's name nor did he remember meeting anyone who matched my description of him. I can’t say that I was all that surprised. I arranged to have this hammered-brass guy retrieve his samples from my office at his earliest convenience. And thanked my proverbial lucky stars for me having escaped from being hammered, or fleeced, or both.

Next in Part Two: A Wild Carroza Chase.

Originally published on 18 January 2009. All text and photos (except as otherwise attributed) copyright ©2009 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Original comments:

thepinoytraveller wrote on Feb 7, '09

are you a writer by profession?

|

jolotamayo wrote on Feb 7, '09

Well said Mr. Cloma! Very interesting story... :P

|

sieshto wrote on Feb 7, '09

Nice! where's part two? =D

|

arcastro57 wrote on Feb 7, '09

..and that's how I met THE Leo Cloma.The Pampanga carroza maker is still atoning for his sin. Hahaha. Can't wait for Part II.

|

rally65 wrote on Feb 8, '09

thepinoytraveller said

are you a writer by profession? Oh no, not at all. Sorry to disappoint you. Ha ha. |

rally65 wrote on Feb 8, '09

arcastro57 said

..and that's how I met THE Leo Cloma. And that's how I met Alex Castro, the Sun-Star Pampanga staff reporter. Ha ha ha. |

yamak wrote on Feb 9, '09

Love this article! Pagkahaba-haba man ng prusisyon, sa simbahan pa rin dating. Is that right? Haha

|

puyat1981 wrote on Feb 9, '09

Hi Leo, very informative piece you have here!

btw, I read part II and I saw pictures of a silver carriage. Forgive my ignorance, but when you say it's made of "silver" then it really is "silver" right? Thanks |

rally65 wrote on Feb 9, '09

yamak said

Love this article! Pagkahaba-haba man ng prusisyon, sa simbahan pa rin dating. Is that right? Haha

Huh? Ano naman ang kinalaman nuon dito?

|

rally65 wrote on Feb 9, '09

puyat1981 said

Hi Leo, very informative piece you have here! btw, I read part II and I saw pictures of a silver carriage. Forgive my ignorance, but when you say it's made of "silver" then it really is "silver" right? Thanks Antique "silver" carrozas were usually of silver-plated brass. However, there were a very few magnificent examples that were made of solid silver. See here: in Santa Rita, Pampanga: http://www.flickr.com/photos/88353092@N00/2353811539/ in Binan, Laguna: http://www.flickr.com/photos/92686790@N00/249753398/ Most of the so-called silver carrozas that can be seen nowadays are of the silver-plated brass kind, especially if they are antique. Many of those have been restored via electroplating. The newer examples are usually made of stainless steel, with hammered designs to emulate the antique examples. One day, someone ought to write a whole article on this subject (if I don't get around to it first). |

No comments:

Post a Comment