Unlike many people, I don’t usually undertake a “Visita Iglesia” (planned visits to a series of churches, as a pilgrimage) during Holy Week. My excuse is, I’m far too busy and preoccupied to do so at that time. Lame, I know.

But what better way to make up for that omission, as well as to get over the feeling of loss after the sensory and devotional stimulation brought about by Holy Week goings-on, than to undertake an off-season Visita Iglesia! Seriously.

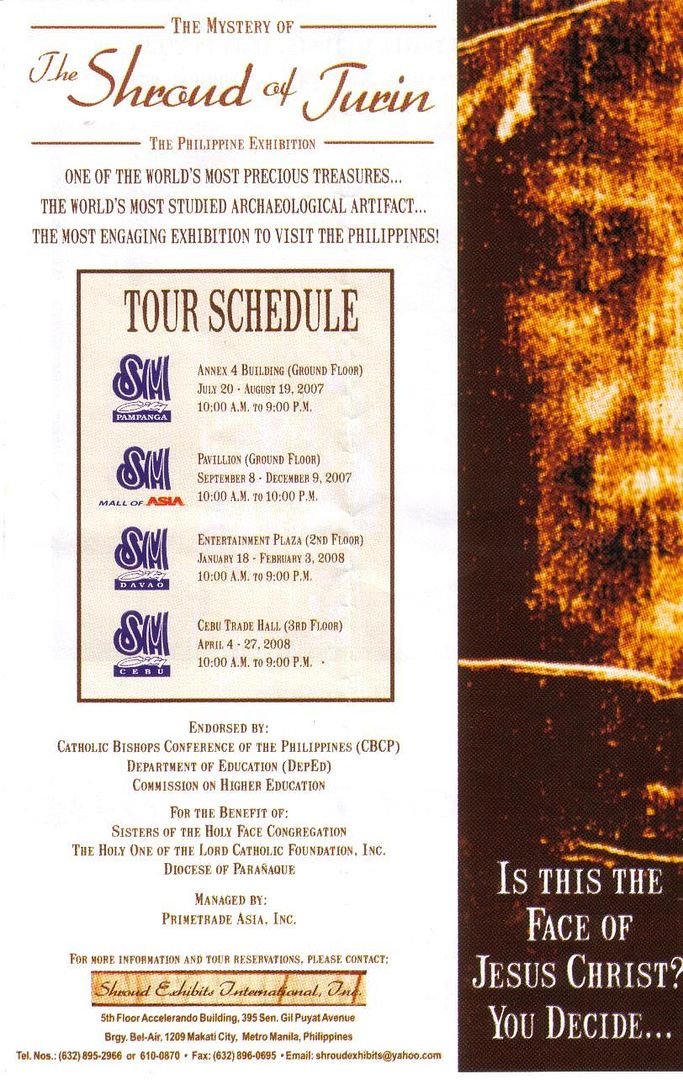

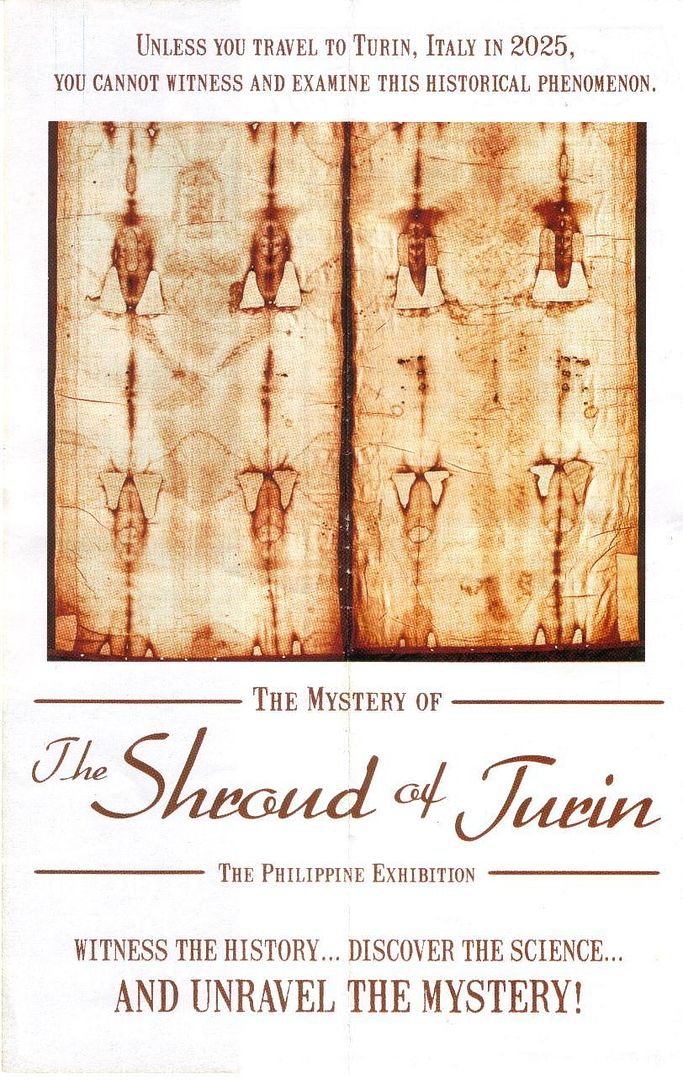

So that’s exactly what I did, together with a small number of like-minded individuals. On a sunny July morning of last year, we piled into a van and started our Visita Iglesia. First stop was the SM Mall in San Fernando, Pampanga. Yes, positively commercial and seemingly unreligious, admittedly. But the reason for this pilgrimage station was the much-talked-about, and in the end, over-hyped, “The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin: The Philippine Exhibition.”

Apart from being not inexpensive (so sue me for the double negative), the so-called exhibition was just an unfresh rehash of material that’s been available in book and video form for many years. You might even have learned more about the subject by watching documentaries shown on television during Holy Week.

The only saving grace, if at all, was that the first part of the exhibit was this not-too-badly-done light-and-sound production number, featuring exquisitely beautiful life-sized seemingly-antique Holy Week processional images, reportedly borrowed from private owners in the Archdiocese of Cebu.

I haven’t been able to verify that attribution, but the anticlimactic part was that, as feared, all photography was forbidden, and so you will just have to take my word for it that the featured processional tableaux of the Agony in Garden, Christ Before Pilate, The Fall of Christ, and The Crucifixion were exceptionally good indeed.

The final antique processional image featured was a slightly-smaller-than-life Dead Christ, positioned on a chest-level platform, and bundled up in a large white sheet. Actually, it was more in the manner of swaddling clothes, as the image was wrapped up all around, with the only part preventing it from looking like a mummy was that the full face was left uncovered. It was expectedly billed as a “miraculous” image, supposedly because blood was being shed from the wound in the side.

The white wrap-around sheet didn’t seem blood-soaked when I looked, thank God. But I’m guessing that some connection with the Holy Shroud was somehow being attempted with the featuring of this image immediately before the Shroud exhibits proper. In which case, I think that it was somewhat off the mark, as the way the Dead Christ was wrapped up—more like crumpled up—in its “shroud” was totally different from how Jesus was supposedly lain in the Holy Shroud—the Body was simply enveloped in the long narrow flat Shroud from heel to head at the back, then continuously across the top of the head from the face down to the toes in front.

As far as I was concerned, the only mystery that needed unraveling was where the previously mentioned antique processional images originated from. And in that connection, how may one take (or get hold of) photographs of those, for addition to one’s photo archive.

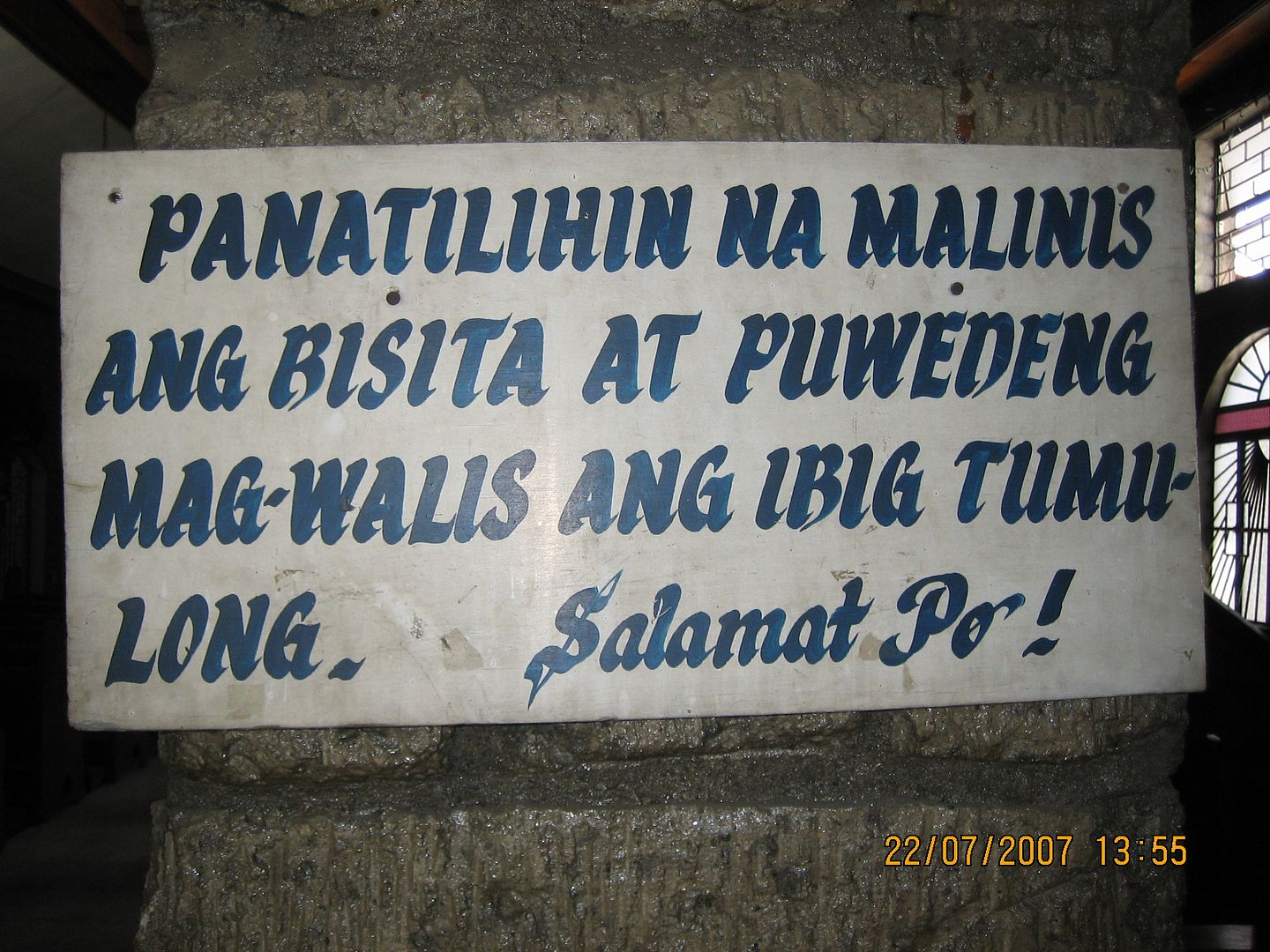

After that underwhelming activity (and a far more satisfying repast at one of the conveniently-located restaurants at the mall), we decide to make up for the lack of appreciable progress, and head for the innards of Bulacan province due south. Exiting at Pulilan, we head east, and decide to stop at a chapel (Visita! – forced connection) by the roadside. This sign greets us upon entry:

Not seeing any brooms around (or maybe we tried not to look too hard), we ignore the request and walk around the interior. A fair-looking Nazareno with a glittery-gold garment is our first object of veneration here.

The glittery-gold garment and loose-fitting crown of thorns are noteworthy.

In another corner was a devotional image of San Isidro Labrador, the patron of this town.

This was apparently a gift to the Chapel from “Kabinataan 1991,” as inscribed on the image’s base.

Perhaps “Katandaan 2031” will have a bequest too – let’s wait around for that.

The main altar of this Chapel was dedicated to what was reputedly a very old and (very unsurprisingly) reputedly miraculous image of a “Cristo Cautivo” (Arrested Christ).

Like many other old venerated Christ images in these islands, it was extremely dark-skinned, partly perhaps because of the passage of time, but also no doubt inspired by the Black Nazarene in Quiapo.

In another part of the sanctuary was a classically-rendered Dolorosa:

It became increasingly evident that the devotees of this barangay really invested in the endowment of their Chapel, with the provision of low-relief painted Stations of the Cross (rather than laminated postcards more usually seen in other places).

But the highlight of this stop has got to be the Santo Entierro in the rear of the nave:

with its large custom-made calandra in wood, metal, and glass.

The feet of this image have been rubbed of its paint by constant touching and kissing of devotees over the years, resulting in something that looks disturbingly like Christ has been infected by a flesh-eating disease.

If the pained and contorted appearance of this Dead Christ might look familiar

this is because this was also featured in the iconic book “Cuaresma” from a few years ago. Take out your copy and try to locate this in there.

Our next stop is the old Pulilan Parish Church in the town proper, where the venerated image we first encounter is yet another Santo Entierro.

This isn’t as well-made as the one in the Chapel, but let’s give it some credit for its gold-appliqued neo-baroque calandra.

Near the altar was what appeared to be a large processional image of Saint Martha, as her feast day was coming up soon.

I really don’t know what to make of her funky threads. Do you?

At a side altar was a fair-looking Marian image

The church’s main retablo is a simple wooden neo-classical affair, with the Resurrected Christ in the top niche.

The town’s patron, San Isidro Labrador, was in the left-side niche.

and his sainted spouse, Maria de la Cabeza, stood on the right side.

In the sacristy just off the altar was another image of Santa Maria de la Cabeza, probably for processional use.

This image clearly demonstrates her ability to cause objects to levitate – for example, the green jar that she would otherwise have to hold by hand quite easily floats.

There is a beautiful large Crucifix on another wall of the sacristy

A tasteful yet practical washstand has been inserted in a niche in one wall.

And the whole thing is watched over by an old brass altar crucifix, now separated from its matching candlesticks.

The exterior of the church from the adjacent courtyard is a feast for adobe fetishists like me.

On one wall of the courtyard is the parish's organization chart.

I like the fact that they trace their reporting line not just to the Bishop and the Pope, but to Jesus himself!

is now accessible – or not – via an iron-grill gate.

This is evidently a heritage-conscious parish, as even the parish office endeavors to be period-reminiscent.

We next go further east in Bulacan and see how period-reminiscent (or not) other churches might be in the area.

Continued here.

Originally published on 1 April 2008. All text and photos copyright ©2008 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Original comments:

Original comments:

zambaleno wrote on Nov 16, '08, edited on Nov 16, '08

I notice that more and more images of the Sto. Entierro are being kept inside churches. What prompted this current trend? Why has this practice come into vogue? Is it because the old families that used to care for these images are now too impoverished to afford their care and maintainance and, as a result, just deeded them over to the church? Wasn't it the case that, in the olden days, the church asked the more prosperous families of the town to commission and care for processional images simply because the church did not have the time and/or the funds to maintain these money pits?

|

rally65 wrote on Nov 16, '08, edited on Nov 16, '08

zambaleno said

I notice that more and more images of the Sto. Entierro are being kept inside churches. What prompted this current trend? Why has this practice come into vogue? Is it because the old families that used to care for these images are now too impoverished to afford their care and maintainance and, as a result, just deeded them over to the church? Wasn't it the case that, in the olden days, the church asked the more prosperous families of the town to commission and care for processional images simply because the church did not have the time and/or the funds to maintain these money pits? It seems that in the case of the newer parishes, it is pretty standard nowadays that the Santo Entierro is church-owned, and kept in the church. Its care and preparation for the procession is usually taken on by one or another church organization, e.g., the Knights of Columbus, etc. What I surmise is that very few families offer to take on this responsibility nowadays because of lingering superstitious beliefs that to do so would invite bad luck, a death in the family, etc. I guess many modern Filipinos are still scared of the Dead Christ. Ha ha ha. On the other hand, the older, pre-war Santo Entierros that have been each "assigned" to a wealthy family in the parish tend to still be with those families even today. However, I was told that even in the past, the images themselves were usually kept in the church, and only rarely in the household of the wealthy family. What is kept with the family is the calandra. An example of this case is the Santo Entierro of Barasoain, Malolos. This seems to have been in the care of the Bautista family since the late 19th century. However, it is kept year-round in an antique stationary "calandra" in a side aisle of the Barasoain church. The wheeled calandra, on the other hand, is garaged in the back of the Bautista mansion a few blocks away. The family still takes charge of its preparation for the procession, and arranges to take the image after the "veneration of the cross" ceremonies on Good Friday. (The antique image is a "convertible" one and is actually taken down from the cross and laid on a wooden stretcher for positioning inside the calandra.) |

arcastro57 wrote on Nov 17, '08, edited on Nov 17, '08

Sta. Martha looks catatonic. And that Sto. Nino, is he standing on a pot? I bet the Entierro with a contorted body was used in a Crucifixion scene as well.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment