In my second visit to Taal in December 2006, I went to the sala window of the Ilagan House (see previous article), and viewed this:

Later upon exiting, I looked out diagonally across the street, and saw it again.

What an interesting structure, I thought to myself. I must visit this later today, I said.

And indeed I did. And when I did, I realized that I had been here before, on my previous visit to Taal in September 2003. This was the venerable Leon Apacible House, originally a 19th century Spanish colonial mansion owned by Maria Diokno, then inherited by her granddaughter Matilde Martinez. Matilde married the revolutionary and ilustrado Leon Apacible, who was lost at sea in 1901, but left an only son, also named Leon, and also gave his name to the house.

Later, the widowed Matilde married the much younger Vicente Noble, who was Governor of the Batangas throughout the 1930’s. It was during this period that an anonymous architect from neighboring Lemery transformed the erstwhile 19th century Spanish colonial to become a thoroughly Art Deco American colonial mansion, completing the work in 1938.

And I realized too why I did not clearly remember having already visited – because photography was forbidden inside. The house, now officially referred to as the “Pook Pangkasaysayang Leon Apacible” (Leon Apacible Historical Landmark) is now administered by the National Historical Institute, and as with perhaps all of the NHI’s administered properties, does not allow indoor photography.

In fact, on my 2003 visit, the only photographs that I was able to take were of the façade, over the roof of my parked van

To see how the inside looks, the diligent heritage enthusiast will have to turn to his Filipiniana library and take out his much-thumbed copies of Filipino Style (Archipelago Press: Singapore, 1997), pages 78 and 79, as well as Batangas: Forged in Fire (Ayala Foundation: Manila, 2002), page 54.

Unlike this amateur point-and-click shutterbug, those books’ professional photographers were obviously able to obtain NHI permission to document the unusual ambassador living room set, the Art Deco light fixtures, and the recurring motif of three interlocking triangles that appears on everything throughout the house, including the embossed ceiling panels, the parquet hardwood floor, and the furniture.

So on this second visit to Taal, the last of my only three shots of the Apacible House is yet another one of its façade, well beyond the reaches of the NHI’s photography-allergic enforcers.

- - - - - -

Just a short distance away, on a parallel street, is the far more welcoming and photography-friendly Goco House.

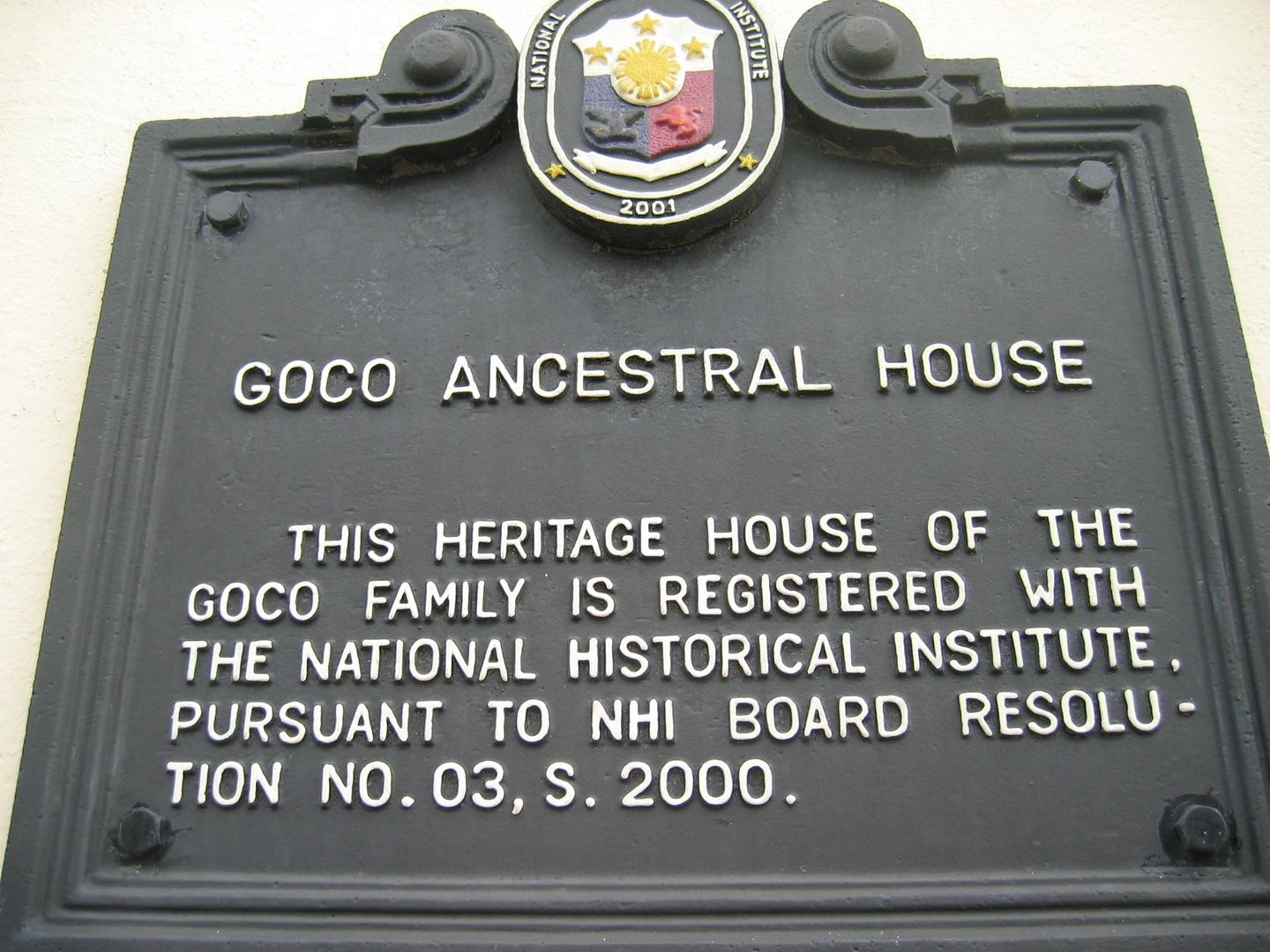

As the marker on the façade of the house shown in the above photo indicates, the owning family took the proactive step of registering their ancestral home with the National Historical Institute in 2000. However, the house continues to be administered by the owners, happily avoiding the photography ban usually encountered in NHI-administered properties.

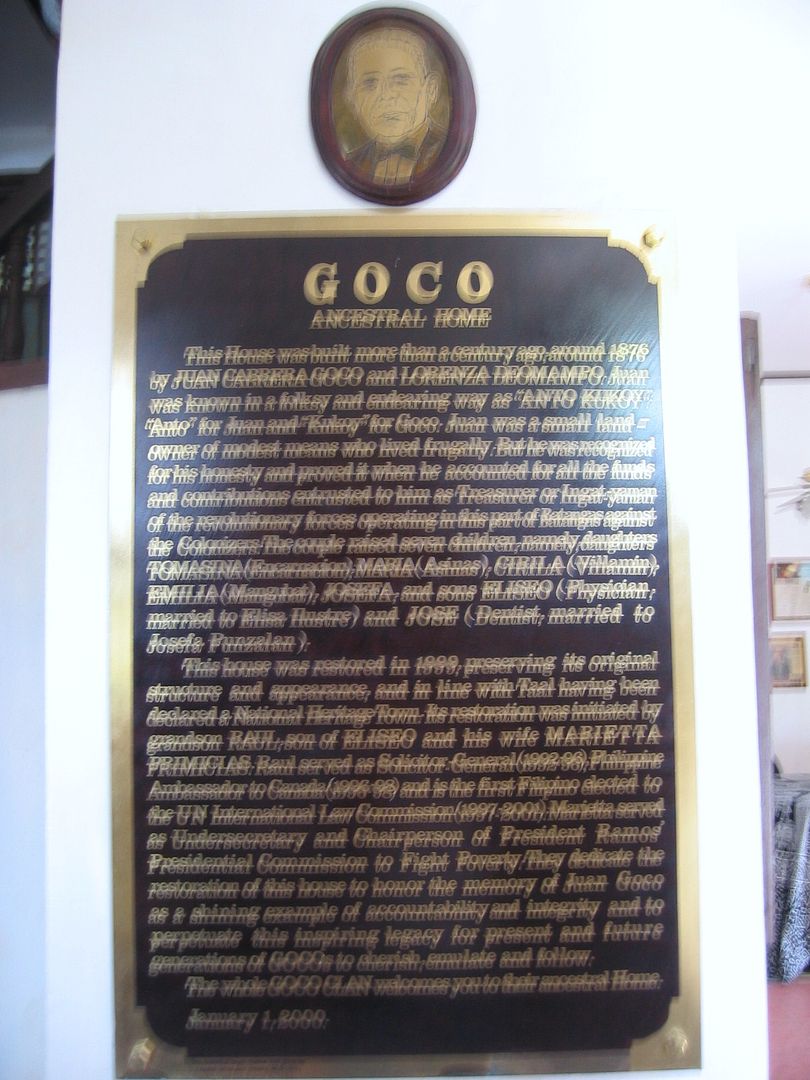

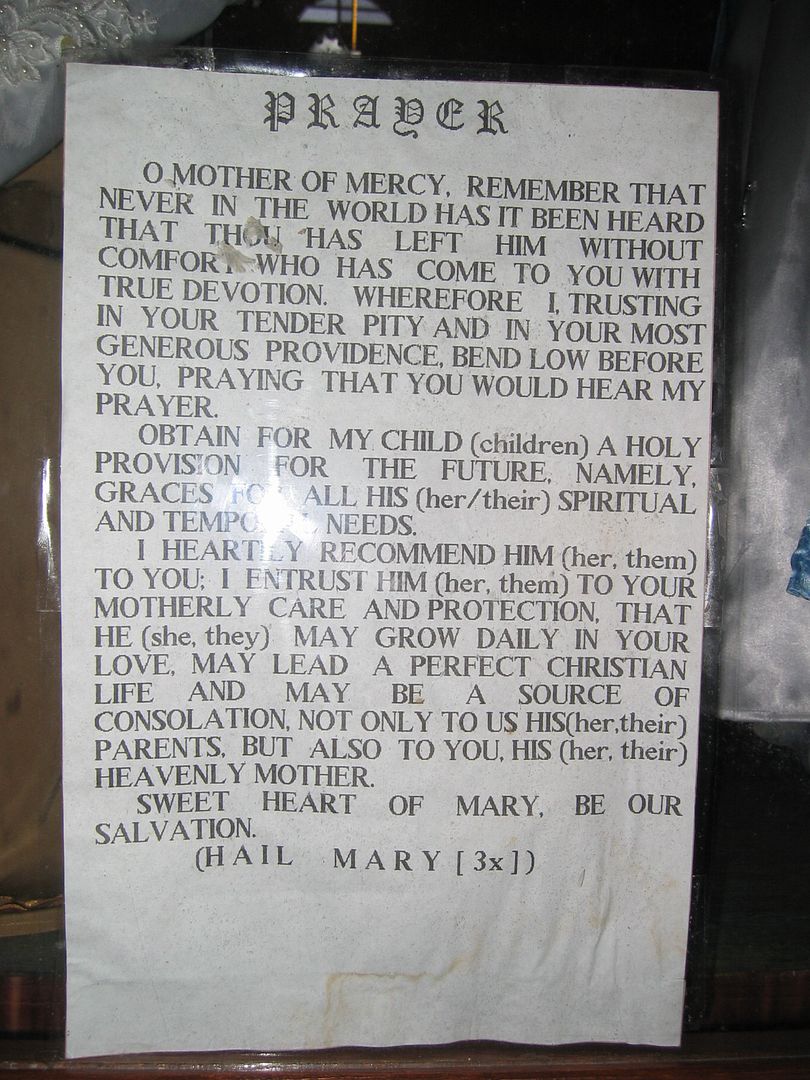

A brass marker right after the ground floor entrance provides more information.

Because my camera was misbehaving (or my hands were simply unsteady from clicking fatigue on this Visit Taal Day), the photograph that I took of it was too blurry, so let me transcribe its contents for you:

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

GOCO ANCESTRAL HOME

This house was built more than a century ago, around 1876, by JUAN CABRERA GOCO and LORENZA DEOMAMPO. Juan was known in a folksy and endearing way as “ANTO KUKOY”: “Anto” for Juan and “Kukoy” for Goco. Juan was a small landowner of modest means who lived frugally. But he was recognized for his honesty and proved it when he accounted for all the funds and contributions entrusted to him as Treasurer or Ingat-Yaman of the revolutionary forces operating in this part of Batangas against the Colonizers. The couple raised seven children, namely, daughters TOMASINA (Encarnacion), MARIA (Asinas), CIRILA (Villamin), EMILIA (Mangubat), JOSEFA, and sons ELISEO (Physician, married to Elisa Ilustre), and JOSE (Dentist, married to Josefa Punzalan).

This house was restored in 1999, preserving its original structure and appearance, and in line with Taal having been declared a National Heritage Town. Its restoration was initiated by grandson RAUL, son of ELISEO, and his wife MARIETTA PRIMICIAS. Raul served as Solicitor-General (1992-96), Philippine Ambassador to Canada (1996-98), and is the first Filipino elected to the UN International Law Commission (1997-2001). Marietta served as Undersecretary and Chairperson of President Ramos’ Presidential Commission to Fight Poverty. They dedicate the restoration of this house to honor the memory of Juan Goco as a shining example of accountability and integrity and to perpetuate this inspiring legacy for present and future generations of GOCOs to cherish, emulate and follow.

The whole GOCO CLAN welcomes you to their ancestral Home.

January 1, 2000.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

If only most other families around were as conscientious of their heritage and as welcoming to others.

As might have been expected from a famously modest and frugal couple, the home of Juan and Lorenzo Goco is simple, unpretentious, and decidely on the small end of the scale, even compared to other ancestral houses in Taal, which themselves tend not to be too palatial in the first place. The façade is made up of just two bays (not the usual three) of equal size, one of which accommodates the main entrance.

The main door is a practical affair of wood planks, with wooden bars in the upper panels to let air and light in, and a postigo (cut-out pedestrian door) with a charming ogee (Moorish-inspired) arch.

This leads directly to the main staircase, which is neither grand nor wide. Its first couple of steps are of tile, and the rest of the ascent is handled in a straightforward manner by simple wooden planks.

There is no antesala to speak of, since the stairs lead directly to the smallish sala, ventilated and illuminated by newly-added antique-style ceiling fans with built-in lights.

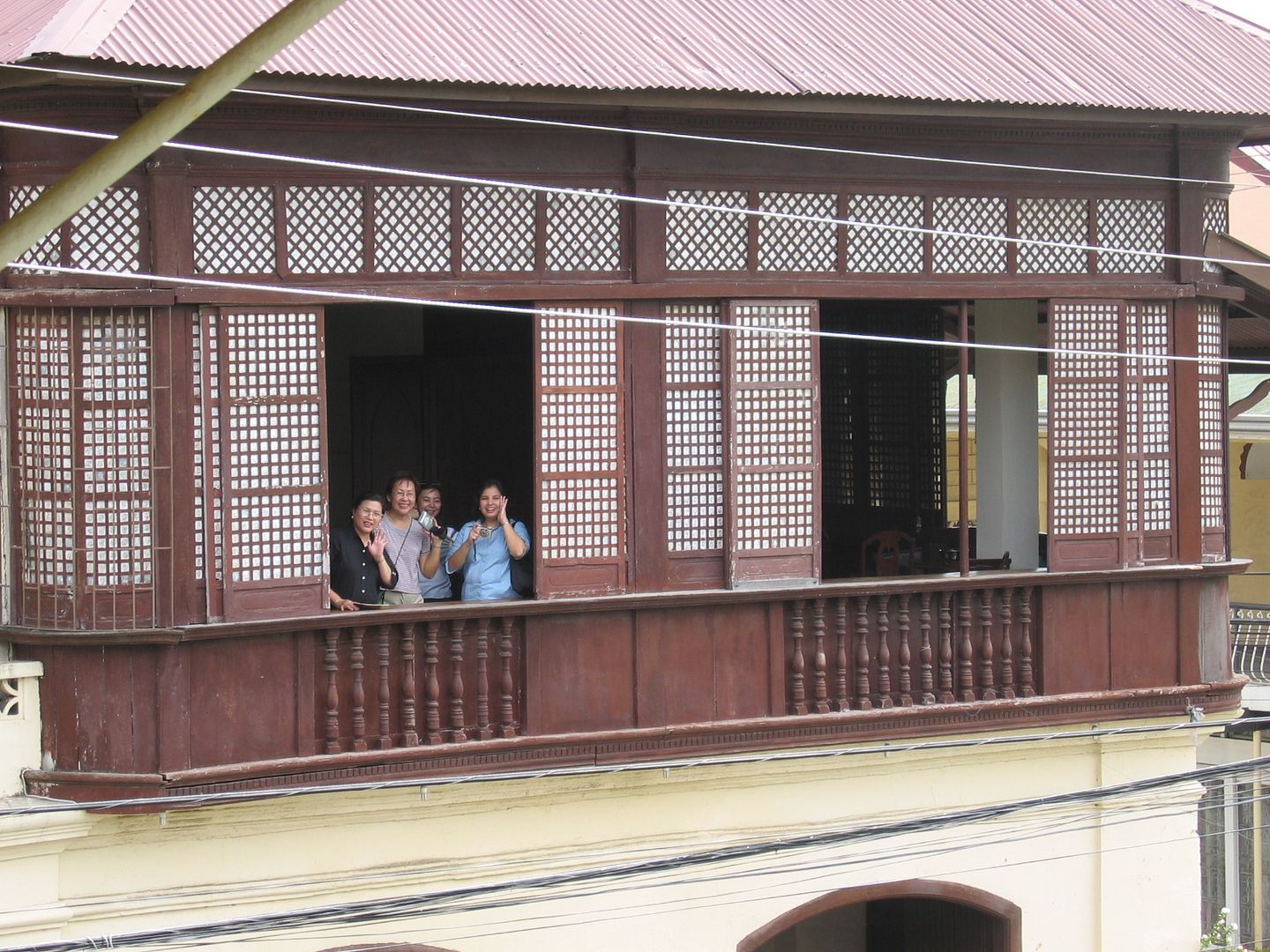

Like the Ilagan House and many other houses of its time in this part of the country, the second floor features wrap-around capiz windows that gracefully curve around the corners.

In truly modest fashion, the one bedroom that I could make out was furnished very simply, with more recent furniture from the first half of the 20th century.

Perhaps the best perspective of this house is in fact seen from the window of the much grander home across it.

But no matter how small, simple, or modest, congratulations are definitely in order to the Goco Ancestral Home and to its owners not only for thoroughly restoring it but also for welcoming the public to visit it free of charge, and for allowing visitors to photograph it. (Did I mention that they allow photography here?)

Here's hoping that more families – including yours and mine – may “cherish, emulate, and follow” their example.

[Continued here.]

Originally published on 23 August 2009. All text and photos copyright ©2009 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Original comments:

antigualla wrote on Sep 9, '09

Yes! I believe it is not the size of the house that matters, but the history of the people who built it, and most of all, how it is lovingly cared for and preserved even to the third and fourth generations.

Thanks for sharing, Leo. |

enm1031 wrote on Jan 7, '10

my sister edna nable robison is coming back to philippines with her daughter and son-in-law this february 2010. we will be roaming around in some beauiful spots of philippines. so, i got a very good idea now i will bring them in this ancestral home of Goco in taal, batangas. i've been passing in that place several times not knowing that there is a goco heritage house to visit in taal. now, i will be promoting this to all my relatives and friends. i am proud there is one like this that was loved, respected and preserved. mabuhay ang goco clan!.

|