By July 1st, 2003, or barely three months since we placed the formal order, the basic sculpture of Saint Martha had been completed by the Vecin Workshop’s talented artisans. This was entirely in baticuling wood, the softwood species traditionally used in the Philippines for religious sculpture.

The left hand was outstretched to hold a tray of bread, and the right hand positioned to grab a palm leaf, just like with the Barasoain Santa Marta.

The front part of the image’s body had earlier been cut away to enable it to be hollowed out. This facilitated the drying process – essential in order to avoid undesirable cracking later on – as well as reduced the statue’s finished weight. This torso front was then put back and secured in place with butterfly joints, clearly seen in this next photo.

Ever tactful when dealing with newbies like myself, Mr. Vecin suggested that I take photos as well with a borrowed wig on the image. Taking one of his several hundred-odd wigs in storage or lying around the workshop and fitting it on Saint Martha’s head, he figured that it would be easier for me to appreciate the sculpture’s appearance and therefore extrapolate its finished look if we allowed it to stop channeling Sinead O’Connor too much (my thoughts, not his).

And perhaps a lighter background might help even more, so Mr. Vecin drags Saint Martha across the room towards another wall.

Mr. Vecin and I took the opportunity to agree on some key points for the final painting, mainly that unlike perhaps other Holy Week processional images of Holy Women around, Saint Martha would not look overly distraught (hence the way her face had been sculpted), and would not even have tears (whether of the glass or the “varnish” kind), but would instead look simply serious and stoic, like its two models the Barasoain Santa Marta and the Quiapo Hidalgo Veronica.

From this point in time, we were looking at a wait of several months, to allow the wood to dry completely inside the workshop, with oil painting to be done just shortly before delivery in the first quarter of 2004.

Indeed, the next major change happened to Saint Martha only right before Mr. Vecin called me back to his workshop, in the fourth week of Lent. I showed up a few days later, early in the morning of Friday, March 26th, 2004, and saw this:

From this point in time, we were looking at a wait of several months, to allow the wood to dry completely inside the workshop, with oil painting to be done just shortly before delivery in the first quarter of 2004.

Indeed, the next major change happened to Saint Martha only right before Mr. Vecin called me back to his workshop, in the fourth week of Lent. I showed up a few days later, early in the morning of Friday, March 26th, 2004, and saw this:

Just like the Barasoain Santa Marta, “our” Saint Martha, now completely oil-painted, had her requisite tray of bread, palm branch, and large key hanging from her waistband. To save on weight, she eschewed a real heavy metal key and had a painted wooden model instead.

She was garbed quite closely to the circa 1900 Quiapo Hidalgo Veronica on which her dressing style was modeled, from the draping of her cape to her cloth headdress.

Her tray, which was of silver-painted wood, looked convincingly metallic, and the buns of bread on it, also of wood, looked good enough to eat.

Her simple round halo was mounted on a metal rod that pierced her veil and her ample jusi (raw silk fiber) wig.

And as we specified, Saint Martha was not distraught, mournful, or teary-eyed, but simply serious. Her relatively large, wide-open eyes, while potentially unflattering up close, ensured that once she was perched on top of her carroza, she would not appear half-asleep to devotees on the ground.

Clearly, Mr. Vecin had much to be proud of, with this, the latest in a long line of Holy Week processional images from his workshop.

Which meant that the only thing unaccounted for was Saint Martha’s carroza. I had actually first seen it a couple of weeks previously, when it was still without its metal appliqués.

But later on this same day, it was delivered by Mr. Vecin’s team to my aunts’ purpose-built garage in Violeta Village, Guiguinto, Bulacan, (the imposing all-adobe structure with large fourteen-foot-tall wooden double doors that we nicknamed "Casita Marta," on the right in this next photo).

But later on this same day, it was delivered by Mr. Vecin’s team to my aunts’ purpose-built garage in Violeta Village, Guiguinto, Bulacan, (the imposing all-adobe structure with large fourteen-foot-tall wooden double doors that we nicknamed "Casita Marta," on the right in this next photo).

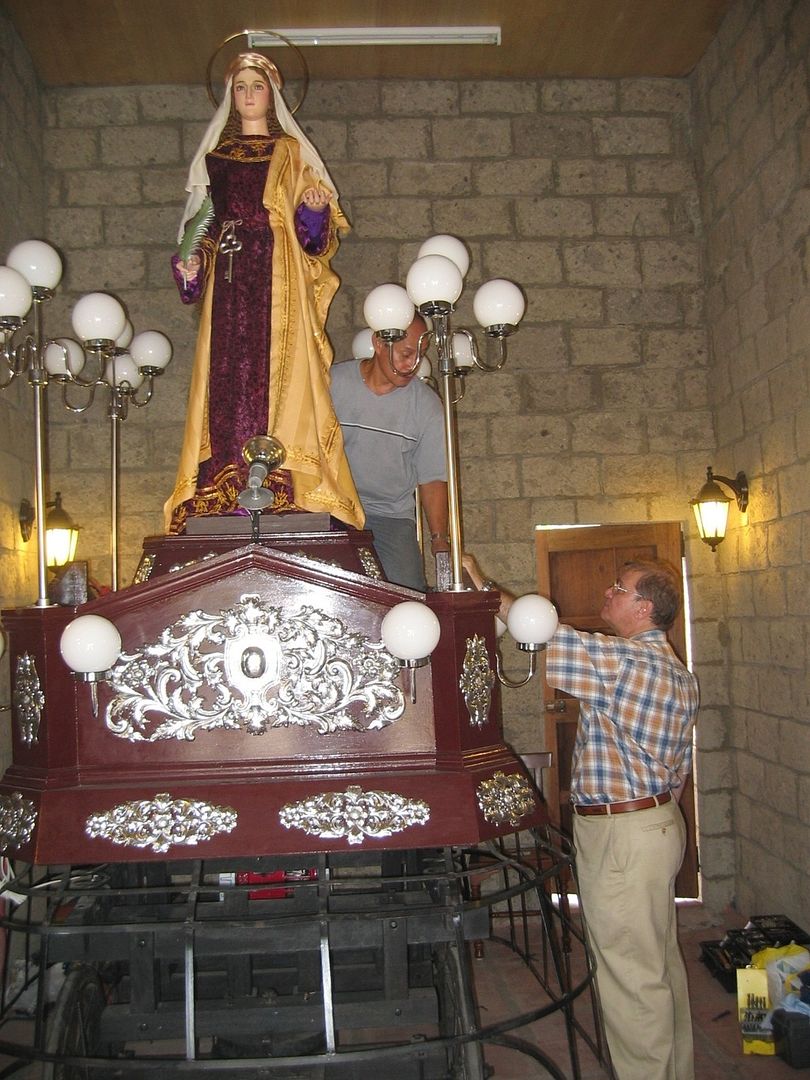

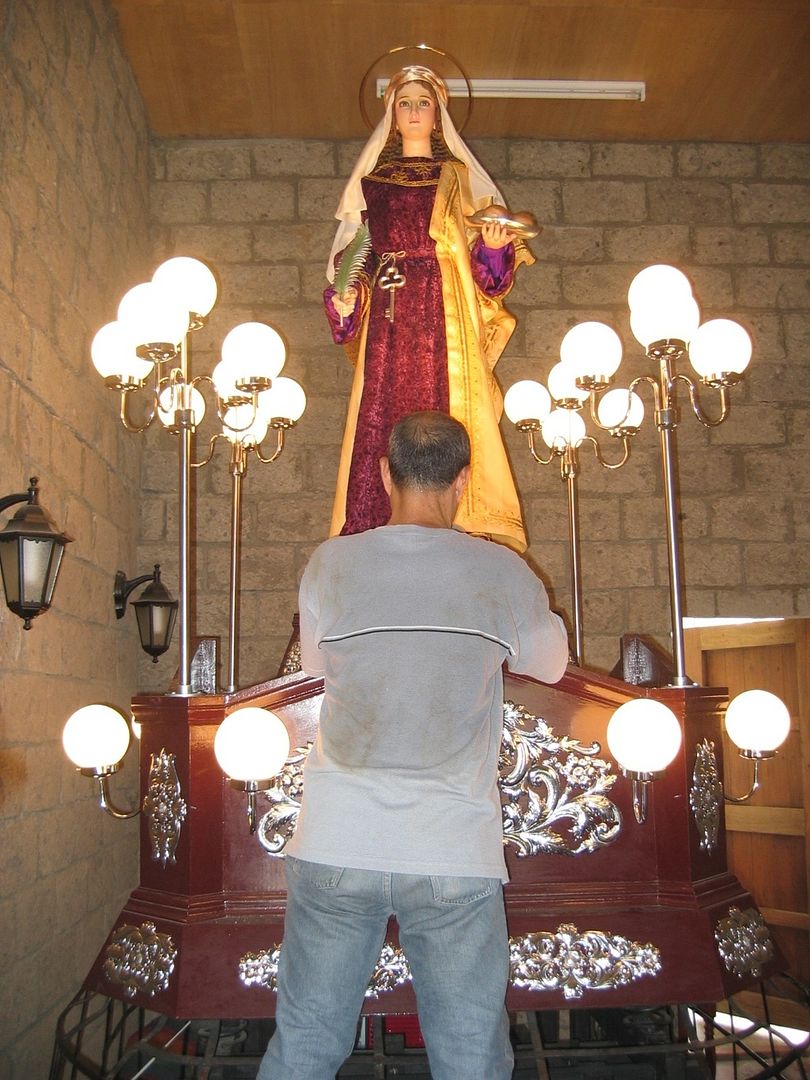

The following day, Saturday March 27th, or eight days before Palm Sunday, I saw the finished vehicle for the first time, inside this new "old" garage.

Strangely enough, Kiko Vecin and I decide to take an excursionary break, while his assistant Mang Jun Puato completed the installation of the arboltantes (lampposts) and pescantes (single perimeter lights). But it wasn’t just any break, as we took the opportunity to pay homage to the Barasoain Santa Marta.

Based on the printed sign on its carroza that I had photographed the previous Holy Week, the owner was a certain Mr. Celestino Ople and his family. In the succeeding months, my aunts made several inquiries in the Barasoain Parish, only to be told alternatively that this Mr. Ople was no longer a Malolos resident, or was deceased, or was otherwise unfamiliar to the community.

It just goes to demonstrate how unreliable conventional wisdom and groupthink are, because as my aunts found out many months after making initial inquiries, (1) “Ka Celing” Ople was alive and well, and lived just a block away from Barasoain Church with his family, (2) His family had been Barasoain residents for several generations already, and (3) He was even the father of a grade school classmate of mine. (Of course, I didn’t make the connection right away – twenty-five years is a long time.)

So it was while our own carroza was being put together that Ka Celing and his family very graciously allowed us to take a look at theirs. Here it was, in their driveway, about to be cleaned, and with its silver-plated appliqués still detached.

Based on the printed sign on its carroza that I had photographed the previous Holy Week, the owner was a certain Mr. Celestino Ople and his family. In the succeeding months, my aunts made several inquiries in the Barasoain Parish, only to be told alternatively that this Mr. Ople was no longer a Malolos resident, or was deceased, or was otherwise unfamiliar to the community.

It just goes to demonstrate how unreliable conventional wisdom and groupthink are, because as my aunts found out many months after making initial inquiries, (1) “Ka Celing” Ople was alive and well, and lived just a block away from Barasoain Church with his family, (2) His family had been Barasoain residents for several generations already, and (3) He was even the father of a grade school classmate of mine. (Of course, I didn’t make the connection right away – twenty-five years is a long time.)

So it was while our own carroza was being put together that Ka Celing and his family very graciously allowed us to take a look at theirs. Here it was, in their driveway, about to be cleaned, and with its silver-plated appliqués still detached.

And here’s one delicate metal appliqué (also called “labor” = originally Spanish for “embroidery” or “needlework”), perhaps inappropriately with an "AVM" monogram, back in its place.

I thought that it was curious that some of these appliqués were customarily detached and stored separately, as with this carroza, so I asked Mr. Vecin about it. He said that indeed, that was sometimes the case with some carrozas, but he advised against this because repeated detaching and attaching will only increase wear and tear, especially for relatively fine and delicate examples. Instead, he recommended that the entire carroza simply be stored in a clean, dry, and well-shaded garage – which protects not just the appliqués but the rest of the carroza as well. (Hence, our "Casita Marta.")

Inside the Ople home, we find Santa Marta standing in the middle of the living room, as if to meet and greet us.

Inside the Ople home, we find Santa Marta standing in the middle of the living room, as if to meet and greet us.

She seemed pleased just to be let out of her unpretentious storage case, inside a small storeroom off the sala.

this was clearly an extremely well-made image.

The proverbial 800-pound gorilla in the room was the as-yet-anonymous creator of this piece. Ka Celing thankfully reveals all, by saying that his late father, who for most of his life was the sacristan mayor of Barasoain Church, was a friend to Santiago “Mantiago” / “Mang Tiago” Santos, the famous master sculptor from Santa Cruz, Manila, active from the 1950’s to the 1970’s.

The elder Ople had commissioned this image from Mantiago in the 1960’s, with the latter’s brother “Mang Baning” the master encarnador painting it. (The Oples had ordered the carroza from elsewhere at the same time.) This image had therefore been processed in Barasoain every Holy Week for about forty years already.

The proverbial 800-pound gorilla in the room was the as-yet-anonymous creator of this piece. Ka Celing thankfully reveals all, by saying that his late father, who for most of his life was the sacristan mayor of Barasoain Church, was a friend to Santiago “Mantiago” / “Mang Tiago” Santos, the famous master sculptor from Santa Cruz, Manila, active from the 1950’s to the 1970’s.

The elder Ople had commissioned this image from Mantiago in the 1960’s, with the latter’s brother “Mang Baning” the master encarnador painting it. (The Oples had ordered the carroza from elsewhere at the same time.) This image had therefore been processed in Barasoain every Holy Week for about forty years already.

At about this time in the storytelling does an 800-pound elephant emerge, for Mr. Vecin reveals that Mantiago Santos was in fact the closest that he ever had to a mentor in the field of sacred images, having been a virtual pupil of the master since Mr. Vecin's youth in the 1960’s until Mantiago passed away in the early 1980’s.

Thus did Mr. Vecin realize why this Santa Marta as he saw it in the photographs that I had given him nearly a year previously looked quite familiar, even though he may never have actually seen it in the Mantiago Workshop of the 1960’s. For it is well-known that an artist’s works always contain his “signature” – something that indicates that it came from him and from no other – which those in the know will usually be able to “read.”

[According to Mr. Vecin, Mantiago’s works (over his long career, he made several processional images for various towns in Bulacan and Manila, among other places) have certain telltale characteristics. Will Mr. Vecin’s own works reveal his signature for future generations? Or do they already show specific characteristics even today?]

After a few more moments to allow Mr. Vecin to admire one of the "rediscovered" works of his mentor some more, I take one more shot of this Mantiago Santos Santa Marta of the 1960’s

Thus did Mr. Vecin realize why this Santa Marta as he saw it in the photographs that I had given him nearly a year previously looked quite familiar, even though he may never have actually seen it in the Mantiago Workshop of the 1960’s. For it is well-known that an artist’s works always contain his “signature” – something that indicates that it came from him and from no other – which those in the know will usually be able to “read.”

[According to Mr. Vecin, Mantiago’s works (over his long career, he made several processional images for various towns in Bulacan and Manila, among other places) have certain telltale characteristics. Will Mr. Vecin’s own works reveal his signature for future generations? Or do they already show specific characteristics even today?]

After a few more moments to allow Mr. Vecin to admire one of the "rediscovered" works of his mentor some more, I take one more shot of this Mantiago Santos Santa Marta of the 1960’s

before we bid it a temporary farewell, and look forward to seeing it again very soon.

By the time we return to our aunts’ house in Guiguinto, it is time to have lunch. Which is exactly what we do. But not before we check out how the carroza has progressed. Not only are all the lighting fixtures now in place, but the bulbous central protrusion of the hammered-metal appliqué also does its job of bouncing off light from my flashbulb quite well.

By the time we return to our aunts’ house in Guiguinto, it is time to have lunch. Which is exactly what we do. But not before we check out how the carroza has progressed. Not only are all the lighting fixtures now in place, but the bulbous central protrusion of the hammered-metal appliqué also does its job of bouncing off light from my flashbulb quite well.

As all the lampposts (four of four lights each) and single lights (a total of eight around the sides) are now affixed and even have their spherical shades in place, evidently, Mang Jun has made productive use of the entire morning.

After lunch, it was time to mount Saint Martha onto her chariot. Which Mang Jun, Mr. Vecin, our driver, and my uncle manage to do quite easily.

With the top platform of the carroza being between six and seven feet from the ground, and Saint Martha being about six feet tall overall (five feet from head to foot, plus about a foot more for the thick wooden base below and her halo above), the overall height of the ensemble worked out to nearly thirteen feet, well within the maximum allowable vertical clearance of fourteen feet needed to get past most road obstructions.

Next step was to fix Saint Martha’s base onto the floor of the carroza, using a pair of large nuts and bolts, one fore and one aft.

Next step was to fix Saint Martha’s base onto the floor of the carroza, using a pair of large nuts and bolts, one fore and one aft.

Throughout this process of setting-up, my family of fellow newbies sits watching inside "Casita Marta," all wide-eyed, like they were born yesterday.

Their work not being over yet, Mang Jun and Mr. Vecin fine-tune the positioning of the image, affix the tray of bread onto her left hand (heretofore empty), and plug the lights into the wall outlet to make sure that they all light up.

Finally, everything is done for the day, and all then present pose for a couple of souvenir shots (excluding the photographer, myself).

And yet, quite a few things remain to be done to get Saint Martha ready for the processions less than two weeks away.

Next in Part Four: Saint Martha in Procession.

Originally published on 30 January 2009. All text and photos copyright ©2009 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Next in Part Four: Saint Martha in Procession.

Originally published on 30 January 2009. All text and photos copyright ©2009 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Original comments:

jamaica1ph wrote on Feb 12, '09

leo,

thank you for writing and sharing this amazing story. thank you too for the help your in my quest for the repair of my Sn. Pedro. Your sharing with me the ground work and research for your Sta. Marta helped me a lot in my own project. I salute you and Kiko for a job well done. warm regards, michael |

arcastro57 wrote on Feb 12, '09

You can say that your Sta. Marta has a twin! Uncanny similarity between your image and Ople's santa.

|

padua08 wrote on Feb 13, '09

Leo: A very interesting read. I look forward to your Part 4.

Michael: Would it be possible for you to share the picture of your San Pedro? Thanks. |

rally65 wrote on Mar 25, '09

padua08 said

Michael: Would it be possible for you to share the picture of your San Pedro?

The story of Mike's San Pedro has just been posted in Flickr Semana Santa Filipinas -- http://www.flickr.com/groups/semana_santa_filipinas/discuss/72157614126461116/#comment72157615866103886

(only viewable to group members). |

padua08 wrote on Mar 25, '09

Thank you Leo for your reply. Perhaps one day I could be a member of SSF so I could view the San Pedro. I wish you well on this year's Holy Week procession.

|

padua08 said

Thank you Leo for your reply. Perhaps one day I could be a member of SSF so I could view the San Pedro. I wish you well on this year's Holy Week procession.

It is very easy to join Flickr Semana Santa Filipinas -- there are no membership fees or extraordinary membership requirements.

Just open a (free) Flickr account, upload some photos that you yourself have taken (of yourself, your religious images, whatever), and then click on "join this group" on the Semana Santa Filipinas page. |

hindi po ba galit si Ka Celing and his family kasi po ginaya nyo po ung kanilang santo?

|

On the contrary, Ka Celing and family were and still are very supportive -- they have even helped my aunts in the setting up of the karo of Santa Marta and the dressing of the image each Holy Week.

It probably helped that Mr. Vecin was mentored by Mantiago Santos, who was the sculptor of the Ople Family's Santa Marta. In general, I observe that Holy Week processional image owners are quite generous and charitable to their fellow santo owners, as they understand that the activity is a devotion, and that the more devotees, the better. |

No comments:

Post a Comment