By July 26th, or a little over three months before All Saints’ Day, the structure was complete, with the red-tegula (tile) roof over the niche area barely visible from the front elevation.

Precast ceramic globes were used as finials on the façade and on top of the walls. They might look like carroza virinas, but no, they won’t light up except maybe if they reflect moonlight.

Complementing the iron-grilled windows, the iron gate was of a straightforward design.

The rose window was as large as it could be without getting in the way of supporting beams on the façade and of the roof line over the niches.

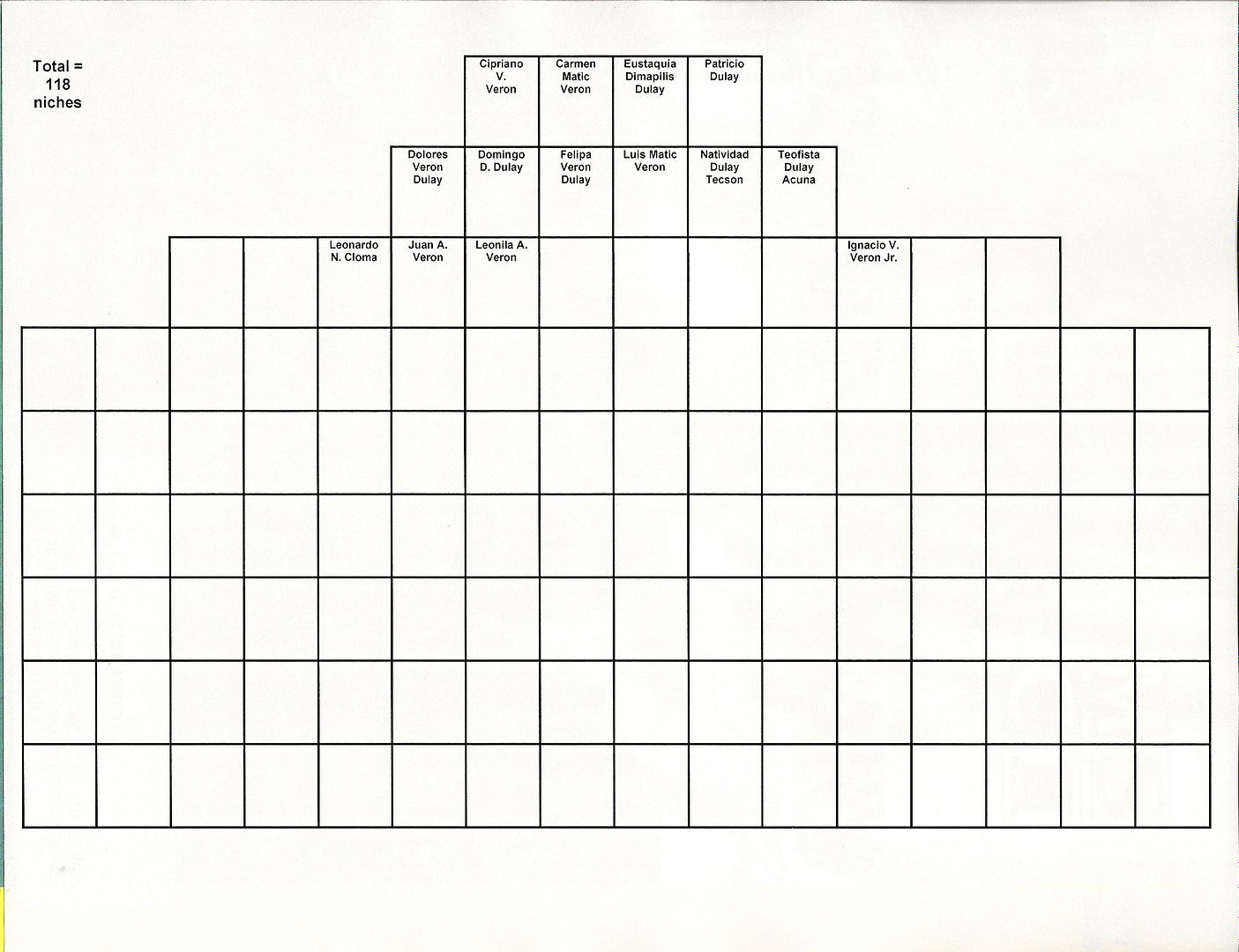

The niches were now topped by a row of four slots, instead of just two initially, because it had since been decided that both sets of great-grandparents (not just the Veróns but the Dulays as well) would be accommodated herein.

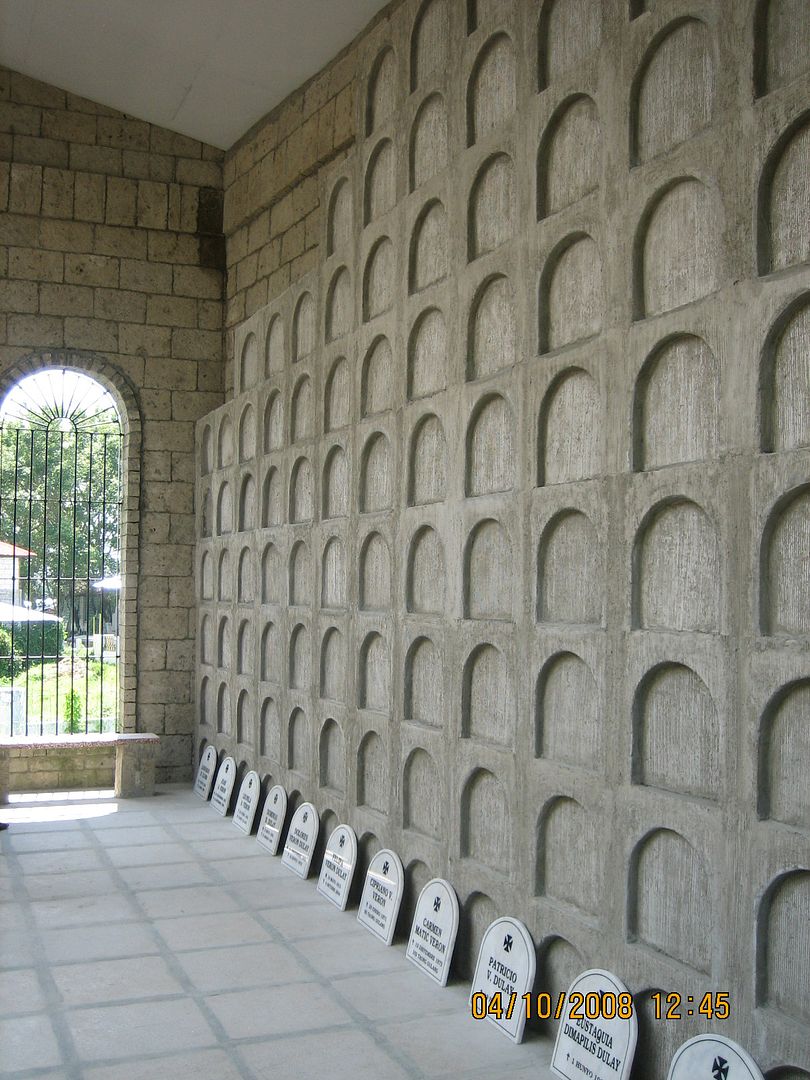

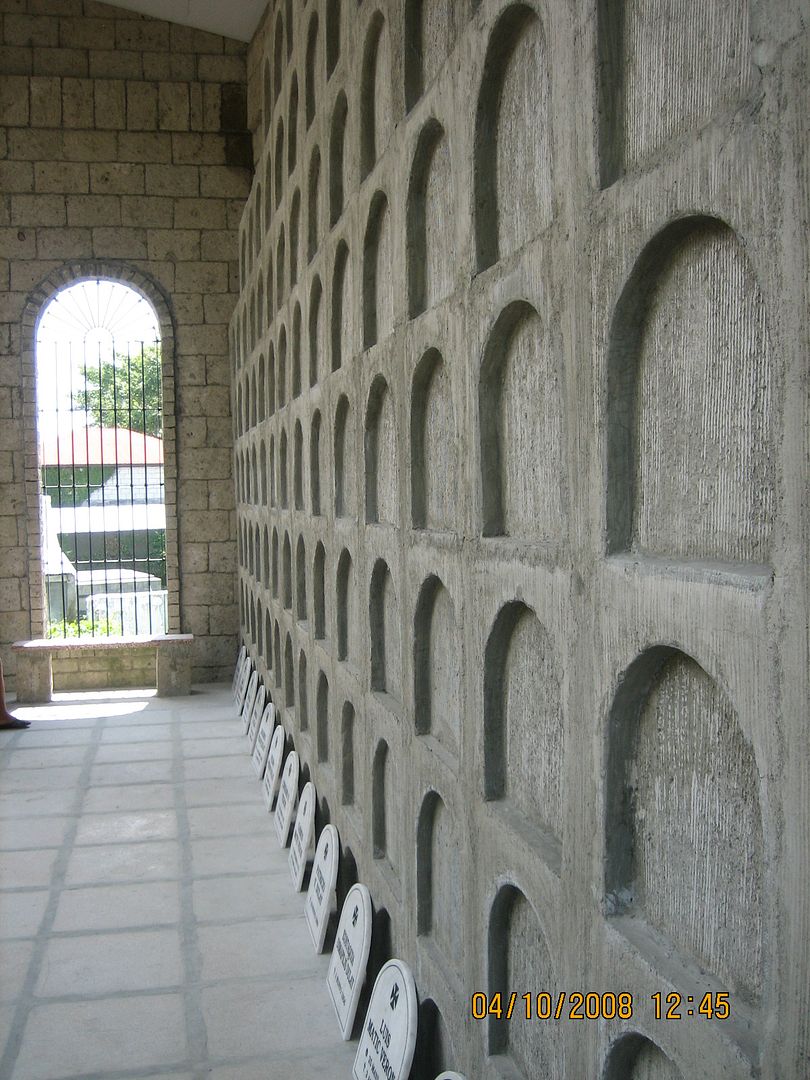

But as had always been intended, the niche area was very organized and neat to look at, whether viewed from the front

from the left

or from the right.

A brief visit on August 9th gave some assurance that moss was growing naturally on the rear wall, no longer necessitating the application of fertilizer (!) on the adobe surfaces as was suggested previously, in order to achieve an ancient, weathered appearance.

While it had been earlier decided to expand the first of the nine rows from two niches to four to accommodate both sets of our maternal great grandparents, a subsequent “recount” revealed that the third row, originally consisting of eight niches following the original design, would now be inadequate by at least three niches. (And no, this was not an ex-future futile attempt to cheat death on the part of some living family members, but perhaps simply a counting mistake.)

We therefore decided to add four niches to the third row (since the addition of only three would make it unsymmetric), as well as to maximize all lower rows to sixteen niches each, to avoid any future niche shortage problems. The additional niches that needed to be constructed are shown in blue in the following diagram.

Within a quick two weeks, the (undetectable) additions had been completed, and the number of niches now totaled one hundred and eighteen, with the top two rows fully occupied by four in the first and six in the second, and with the third row of twelve niches having four occupants so far, for a total of fourteen current residents in all.

With All Saints’ Day 2008 approaching, it was time to get on with that most important final step – the provision of new tombstones. The previous tombstones were obviously going to be unsuitable, as they were (1) large and rectangular, significantly larger than the fronts of the new niches, and (2) stuck to the original full-body niches, now under several feet of soil.

We had previously decided to go for arch-shaped tombstones, inspired by the niche fronts in the Nagcarlan Cemetery, as well as the hundred-year-old tombstones in the San Rafael Parish Church nearby. By our September 20th visit, or barely six weeks before All Saints’ Day, the arch-shaped niche fronts were complete, ready to receive their custom-made fitted tombstones.

To ensure uniformity, our masons traced an arch-topped shape on plywood, closely following examples inside San Rafael Church, and used this in forming the niche fronts

The resulting wall of niches was an interesting sight, even from extreme angles.

Diagonally across this mausoleum was a smaller plot containing the remains of our Dulay great-grandparents and two of their daughters.

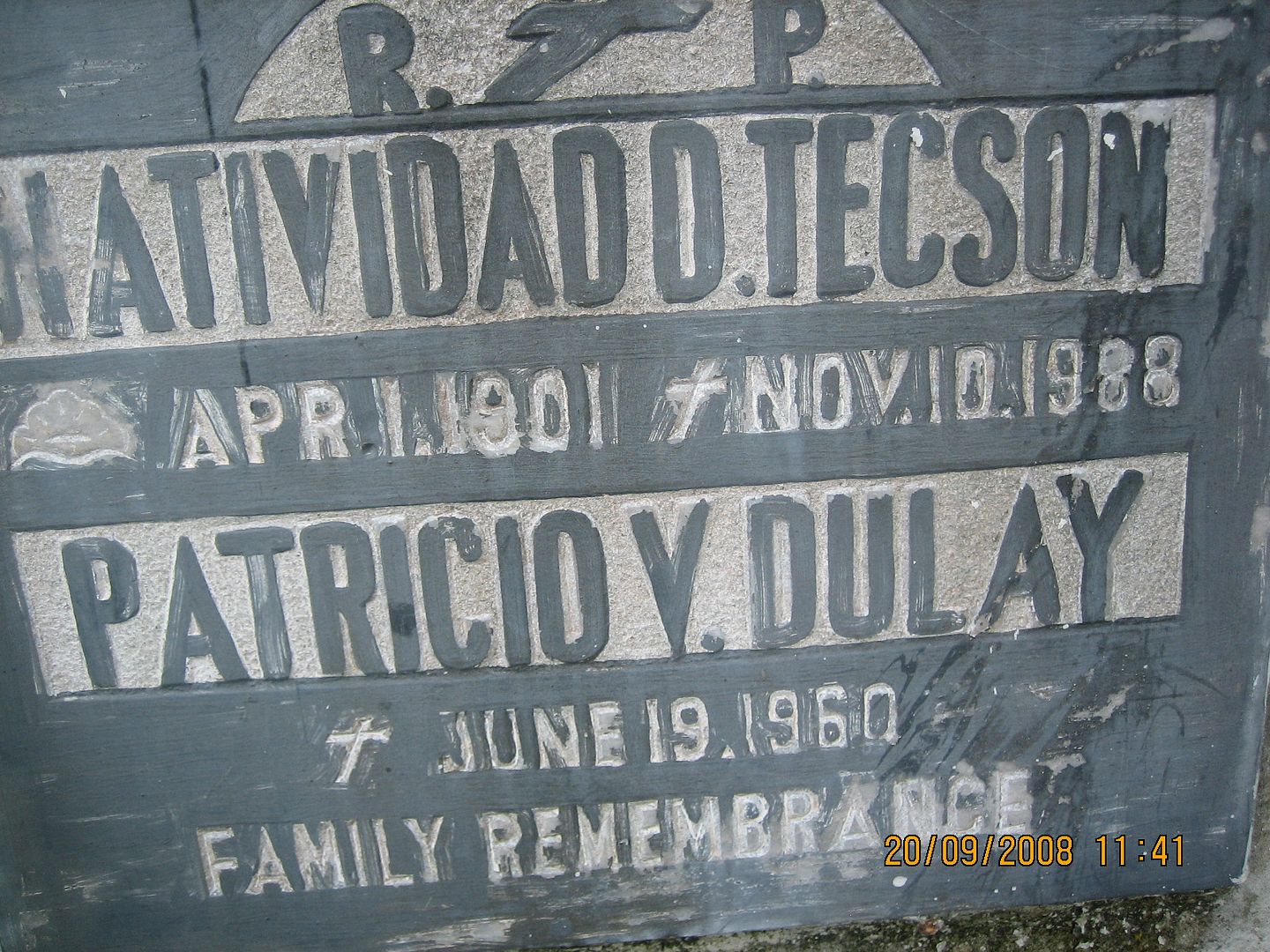

Except for the most recent burial here in 2007, all their remains had already been transferred to the niches in the new mausoleum. I however had to photograph the old tombstones to keep a record of the dates of their deaths.

Looking back across the street to the larger, newly-rebuilt mausoleum, here is the view.

Walking uphill along the cemetery road, one tries to take in the mausoleum’s tall and wide façade.

Going slightly past the mausoleum further along the road, here’s what the view looks like.

Returning to the mausoleum’s doorway, we are welcomed (not yet as residents but as visitors) by a ramp made with the rough underside (for traction) of 20-inch square slabs of piedra china (Chinese granite), and by the wrought-iron gate’s folding panels on both left- and right-side leaves (newly-reconfigured from the single-panel door leaves previously to minimize the swing area).

And inside, the rain-drenched walls were starting to acquire more naturally-grown moss.

I left the San Rafael Cemetery with the names, birthdates, and deathdates of our fourteen mausoleum residents, as well as a plywood copy of the arch-shaped pattern used for forming the niche fronts. I then took these to a marble supplier highly recommended to us by friends, Prit Enterprises in Guadalupe, Makati City.

From the plywood pattern, the Prit people were able to cut white Indian marble (labeled “Rhapsody” in their catalogue) to the exact required shapes and sizes, and subsequently etch the relevant names and dates using computer-based technology and a sandblasting process, avoiding manual chiseling altogether and completing each tombstone’s inscriptions in just under half an hour. In just a few days, the fourteen tombstones were ready for pick-up, which I then delivered to San Rafael on Saturday October 4th, less than a month before All Saints’ Day.

I laid them in a neat row on the floor and leaned them against the niches, on the smooth floor (also made of 20" x 20" piedra china slabs like the entrance steps, but with the smooth side instead exposed here)

just to check for overall color compatibility.

Which also allowed me to photograph each pair of tombstones for documentation purposes. And run down the list of residents, for all of you to get to know them better (since it is unlikely that you will meet any of them, at least not in this lifetime).

Cipriano V. Verón and Carmen Matic Verón were my mother’s maternal grandparents. As Tatang Panô and Ináng Carmen died only on 23 January 1971 and 13 December 1973, I remember them quite well from my early childhood. They themselves did not know precisely when they were born, but using certain snippets of information (e.g., she was older than he was by about five years; she was about thirty when she married; their eldest child was born about a year after marriage), it was conjectured that they were born in around 1876 and 1871 respectively; he was about ninety-five at his death; and she was about a hundred and two when she died.

Patricio V. Dulay and Eustaquia Dimapilis Dulay were my mother’s paternal grandparents. (Her maiden name is actually misspelled in the original lapida that we saw earlier.) Again, there are no records of when Ingkóng Tisyo and Impóng Takya were born, but assuming that they were contemporaries of their balaes, they would have been octogenarians when they died on 19 June 1960 and 1 June 1956 respectively. Looking at photos of them taken in the 1950’s, this conjecture of their ages is entirely plausible.

An interesting observation is that both their deaths in the month of June must be a natural consequence of their having been great devotees of the Sacred Heart of Jesus – they would walk hand-in-hand to early morning Mass every day, crossing the plaza to the San Rafael Church directly across their house until shortly before they died.

The next row is occupied by children of both these venerable San Rafael couples. Dolores Verón Dulay (31 December 1902 – 15 June 1972) was the eldest child of Tatang Panô and Ináng Carmen. “Loleng” was a much-awarded Mathematics and English teacher at the Bulacan High School (later the Marcelo H. del Pilar High School) in Malolos, teaching Calculus to high school students decades before it became the norm.

One of her three sisters (one settled in Malolos and is buried there; the other one migrated to the USA in the 1950’s and died there a few years ago) was Felipa Verón Dulay (16 May 1912 – 4 October 2004), who, like her Até, was a schoolteacher. Except that Felíng taught Grade One in the Caingin (San Rafael) Elementary School for four decades, and several generations of Caingin natives have therefore undergone her schoolmarming. Because she had been buried less than five years ago, her remains are not yet suitable for relocation to the niche area, and are still in their original above-ground (now underground) niche beneath this new Mausoleum.

Luis Matic Verón (25 May 1904 – 2 April 1985) was one of two sons of Tatang Panô and Ináng Carmen (the other was a World War II guerilla and was never found, presumed killed). Like his father, he was a professional farmer and personally tilled the family-owned farmlands in the area. Also like his father, he exhibited the prominent Verón forehead, i.e., a well-receded hairline. (Now you know where I get it from.)

Natividad Dulay Tecson (1 April 1901 – 10 November 1988) was the eldest child of Ingkong Tisyo and Impong Takya. “Nanang Tabâ” (yes, she was on the heavy side -- I wonder which came first, her nickname or her physique?) was a part-time entrepreneur (roadside canteens) and full-time housewife (she was married, and widowed, twice). Nonetheless, she found time to care for her parents in old age, perhaps partly because she had no children. Like her parents, she was originally buried in the small Dulay Mausoleum across the street, and now joins them in this new improved Verón-Dulay Mausoleum.

Teofista Dulay Acuña (15 July 1917 – 18 April 2007) was the youngest sibling of Nanang Tabâ, and was a schoolteacher. Like her Até, Nanang Inê was married and widowed twice, but remained childless. She shared housekeeping and parent-caregiving duties with her Até as well. Because she died just a year and a half ago, her remains will stay in the old Dulay Mausoleum until they are suitable for relocation to the Verón-Dulay Mausoleum niches, perhaps a couple or so years from now.

One of those on the third row of niches is Ignacio V. Verón, Jr. (5 August 1940 – 31 January 1986). “Junior” was the son of another of Tatang Panô’s and Ináng Carmen’s daughters, who just happened to marry a Verón first cousin, hence Junior's (retained maternal) surname. Like his grandfather Tatang Panó and his uncle Luis, he was a professional farmer, and although he was born in Malolos (his mother had relocated there to marry his father, who was from the Malolos branch of the family), he relocated to San Rafael for this purpose. He sadly died relatively early due to liver disease.

Another member of the third row is Leonila A. Verón, who was Luis’ eldest daughter. “Lilay” was a famed beauty in her time, and her extant photographs certainly provide evidence of this. Sadly, she died on 22 January 1952 from acute typhoid fever. Her birthdate is unrecorded, but family members are certain that she was just twenty-three years old at the time of her death.

The final member of the second row is Domingo D. Dulay (12 May 1903 – 31 March 1980), eldest son of Ingkóng Tisyo and Impóng Takya. “Menggoy” married Loleng in the early 1930’s, and they settled in Malolos, he to work for the provincial government, and she to be a schoolteacher in the provincial high school. (Among their four children is my mother.) Some years after Loleng died, this ever-practical family conveniently arranged for Menggoy the widower (by then in his 70's) to marry Loleng’s younger spinster sister Felíng (by then in her 60's), allowing them to provide each other the security and companionship that they both needed in old age. Thus did these two families become linked twice over.

One of the last two members of the third row is Leonardo N. Cloma (4 July 1934 – 15 April 1986). “Nardo” married the eldest daughter of Menggoy and Loleng in January 1965, relocated to Malolos from Pasig, and shortly afterwards became my father. He founded and managed a number of business enterprises in and around town for the better part of the two decades that he was a (completely-assimilated) Malolos resident. His own father was originally from Bohol (where it seems all Clomas originate), relocated to Pasig at a young age, married into a local family, and was presumed killed as an urban guerilla during World War II.

Finally, Juan A. Verón (23 November 1932 – 26 December 1989) was one of Luis’ sons and was Lilay’s brother. “Juaníng” was a professional engineer and engineering professor, and needless to say, also exhibited the prominent Verón forehead. His widow Lilia is now the head of the family’s San Rafael branch, and was the persevering onsite manager for this family mausoleum project.

At this point, one might rest on one of the four granite benches (slabs salvaged from the treads of a pre-war mansion’s staircase and found in an antique shop’s bodega).

Two slabs are positioned at right angles at each end of the niche area.

And before leaving, I took an acute-angle view from one end, just to check for (near-) geometric perfection.

On Saturday October 18th, exactly two weeks before All Saints’ Day, the tombstones were affixed to the niches.

And even if the relatively fresh remains of Felíng and Inê were not yet in their assigned slots, we attached their new tombstones to their assigned slots nonetheless, since they’re not all that difficult to remove and return in place anyway.

Additionally, the iron candle holders had been affixed to the wall of niches at shoulder level, right above the third row from the bottom.

There is one candle holder positioned at every other column division, for a total of eight candle holders in all.

By All Saints’ Day, everything was in place. Family members and guests hung out in the comfort of the roofed niche area while rain drizzled all around.

The rain not only caused the structure’s walls to acquire light vegetation and desirable water stains,

but also allowed the carabao grass (transplanted from various wild-growing roadsides in the vicinity, rather than via a professional landscaping service) in the quadrangle to thicken, bordered by the same 20" x 20" piedra china slabs (rough side exposed) that made up the floor of the niche area (smooth side exposed) and the entrance steps (rough side exposed).

Despite the intermittent rain, the sky was clear enough most of the day to enable the structure’s profile to be clearly seen, even from within.

It was just as well, as the road outside was far too congested and muddy to let me take a photo of the façade.

Fortunately, we were comfortable inside our spanking-new yet trying-to-look-old family mausoleum for several hours that day, doing all the usual things that Filipinos do on All Saints’ Day – chatting,

keeping candles lit,

looking at (way-too-high-up) tombstones,

preparing and serving food,

and just hanging out.

And as for me, you know where to find me fifty years from now – somewhere in the fourth row from the top.

Originally published on 29 November 2008. All text and photos copyright ©2008 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Original comments:

johnjohncastro wrote on Dec 5, '08

wow!

|

overtureph wrote on Dec 6, '08

Wow! Nice! Great taste in design Mr. Cloma.

|

jolotamayo wrote on Dec 6, '08

Congratulations Mr. Cloma! A job well done...

|

rally65 wrote on Dec 14, '08

Thanks for the appreciations.

Now, on to the next projects. Ha ha. |

angelflame061589 wrote on Dec 14, '08

Very nice po! Very well done!

;-) |

antigualla wrote on Apr 11, '09

Leo, nakakahiya mang aminin dito sa multiply, pero sasabihin ko na rin: NAKAKAINGGIT TALAGA! Hahaha. I just hope that someday, I will have the patience to honor my ancestors and immediate family members with a worthy mausoleum. Ang galing mo, Igan. Congrats!

|

rally65 wrote on Apr 13, '09

Thanks for the appreciation, Louie. If you like visiting cemeteries, do visit this one if you get the chance.

|

timmoffy wrote on May 11, '09

hi, any relation to the dulays of Northern Samar? Just curious....thanks!

|

rally65 wrote on May 11, '09

timmoffy said

hi, any relation to the dulays of Northern Samar? Just curious....thanks!

My Dulay ancestors from San Rafael, Bulacan originally migrated there from the Ilocos region, so I don't believe that I am closely related to the Dulays of Northern Samar.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment