If there is any place in the Philippines other than Vigan that deserves to be better known as a heritage town, it has got to be Taal in Batangas province. While not as old or as large as the Ilocano Spanish colonial settlement whose structures go as far back as the 17th to the 18th centuries, Taal’s 19th century wealth, founded first on cotton, and then on sugar, and also on shipping from the nearby port of Lemery, allowed it to build rather fanciful Art Nouveau and early 20th century Art Deco ancestral houses that are probably not found in as close proximity to each other anywhere else.

A genuine Akyat-Bahay Gangster must therefore visit Taal. Which is why I have myself gone twice, in 2003 and in 2006. And I’d go again, if I can manage it, before 2009 is over, to make this a truly triennial habit.

Because it’s a fairly lengthy land journey southwards from Manila of perhaps as much as three hours, depending on road conditions, one must leave the city early. And one must thank God for a safe arrival, by first visiting the venerable Taal Basilica. Here is the very wide five-bay façade, as viewed from the extreme left side and across the street.

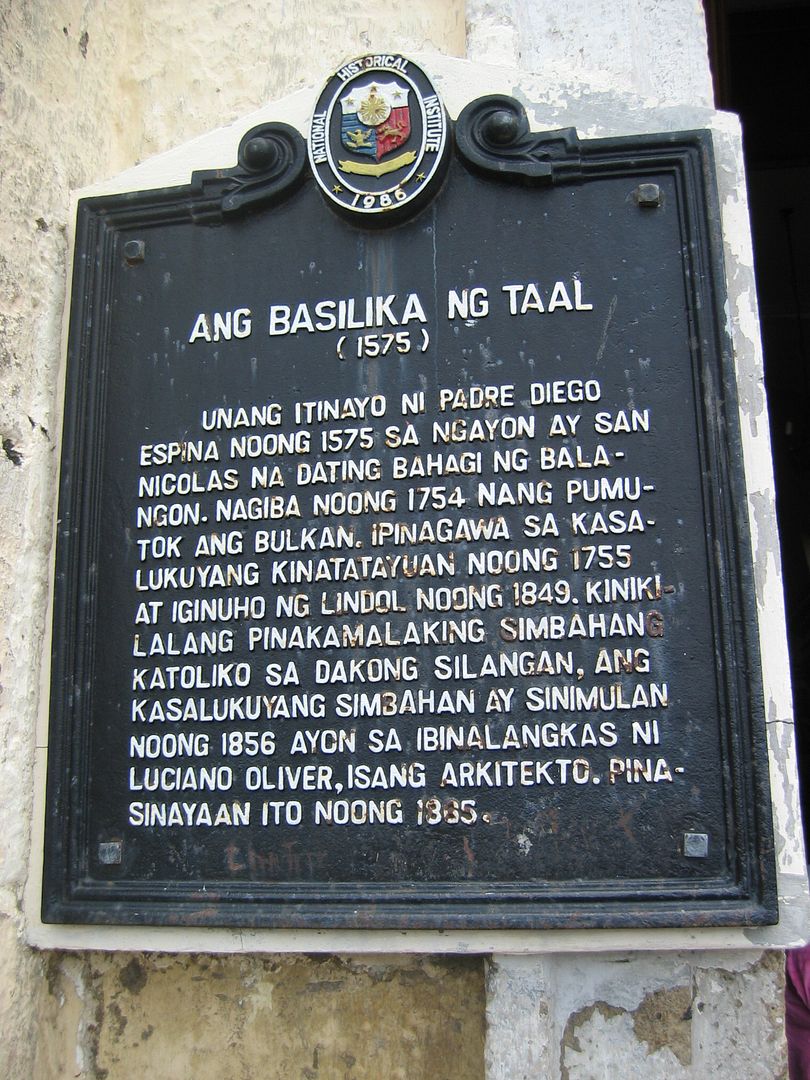

This huge structure, sometimes billed as the largest Christian building in Asia, or the Far East, or South-east Asia, or the Philippines – reliable Guinness-Book-worthy statistics are difficult to come by – is definitely the biggest structure of any kind – in Taal. The original church was built in 1755, but was heavily damaged in an 1849 earthquake. The present church was begun in 1856 and was completed in 1865. The historical marker on the façade is the reliable source of this information.

The main doorway, in the middle bay of the five, is supplied with a pair of tall door panels, of which this is one.

Inside, the width of the structure is put to good use in the provision of four wide rows of pews, and proportionatey wide aisles everywhere that had also made available more than enough space for its generous and wealthy patrons to furnish it with numerous life-sized religious images, starting with this crucifix towards the rear of the nave, near the entrance.

If I’m reading the much-darkened brass plate on its base correctly, it was endowed by a Miss Julia A. Buck on June 22, 1941, and was blessed the following August.

The length of the structure expectedly allows for a full set of evenly-spaced wall-mounted Stations of the Cross, only one of which I was able to photograph given the lack of time (and more interesting subjects to pay attention to).

Up front towards the altar, the breadth of the structure is again in evidence, with a deep sanctuary space holding a rather oversized stone retablo of a relatively miniscule image of the Risen (or Ascending) Christ, and a trompe-l’oeil-painted apse overhead.

Expectedly, the dome over the transept, right above the front part of the nave, is very high and induces either vertigo, or fear that the heavy-looking wrought-iron chandelier is going to crash down on the congregation.

The patron of this parish is Saint Martin of Tours, an early Christian Frenchman who was Bishop of the self-same town in the Loire Valley.

His personal story is interesting, because earlier in his life he was a soldier, who in an act of charity (or maybe chivalry), gave his cloak to a beggar. In a subsequent dream, Christ appeared to him wearing the same cloak, providing confirmation that, “Whatsoever you do to the least of My brothers, you do it unto Me.” Here is a processional tableau parked in a side altar of the Basilica, depicting Martin mounted on his horse and giving his cloak to the aforementioned beggar.

In a side aisle is also parked a Holy Week processional tableau of the Crowning with Thorns.

And beside it is a fully-carved image, in glass-and-wood urna, of Saint Jude Thaddeus.

In another side altar is a small image of an anonymous saint.

He is difficult to photograph well in his glass case, but he can be seen exposing his wounded breast and clutching his Bible or breviary.

I’ve consulted a number of santo experts online and off to determine this saint’s identity, and their suggestions range from the Jesuit San Francisco Javier (exposed breast representing heart inflamed due to intense love for Christ) to San Felipe Neri (heart threatening to spring out of chest due to ardent love for Christ) to the Franciscan San Pedro Bautista (but where’s his usual iconography of a spear, the instrument of his martyrdom?), or the Capuchin Saint Fidelis of Sigmaringen (though perhaps too obscure for Taal).

But because of those wounds on the feet and hands and the brown habit, and despite the somewhat unusual (to me) baring-of-breast depiction and the absence of his usual skull iconography, another santo expert posits that this must be the stigmatist and founder of the Franciscans San Francisco de Asis. Any other suggestions?

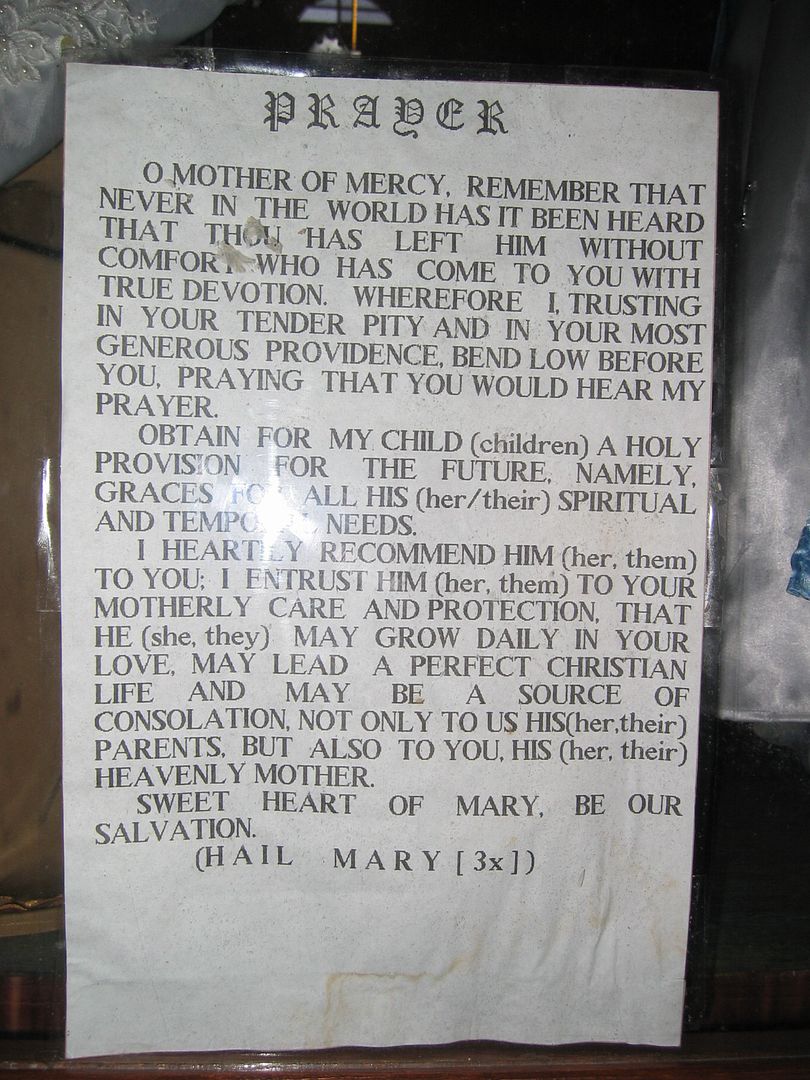

In another aisle is this unusual tableau depicting a mother offering her newborn infant to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

And the suggested prayer to be said by the devout parent is clearly displayed in large font.

A church this large and so well-endowed throughout its history would be incomplete without an image of the Dead Christ. Thanks to “Kap. Domingo Sanches,” we are not found wanting.

And, appropriately, a life-sized processional image of the Most Sorrowful Mother is not far away, rather anachronistically holding a purple rosary.

If there are many processional images holding court in the aisles of this basilica, there are at least as many processional floats parked in whatever vacant slots are still available. Here, for example, is an unusually lean hammered-metal carroza, ready for trotting out at the next processional occasion.

Strange-looking carrozas seem to be all the rage in Taal. Here is a boxy all-wood carroza, really just a box, that dispenses with such niceties as cloth skirting and light posts.

And if having one of this kind is unusual, two of it in the same location is near-apocalyptic.

This one must be even more strange-looking (or not) that it decides to cover up and hide.

The generous patrons of these endowments over the past century and a half are still in evidence, via their memorial stones set into the floor and walls, presumably with their bones beneath or behind. Here embedded in a wall is Doña Micaela Reyes de Agoncillo, who appears to have died in Manila on 13 March 1901.

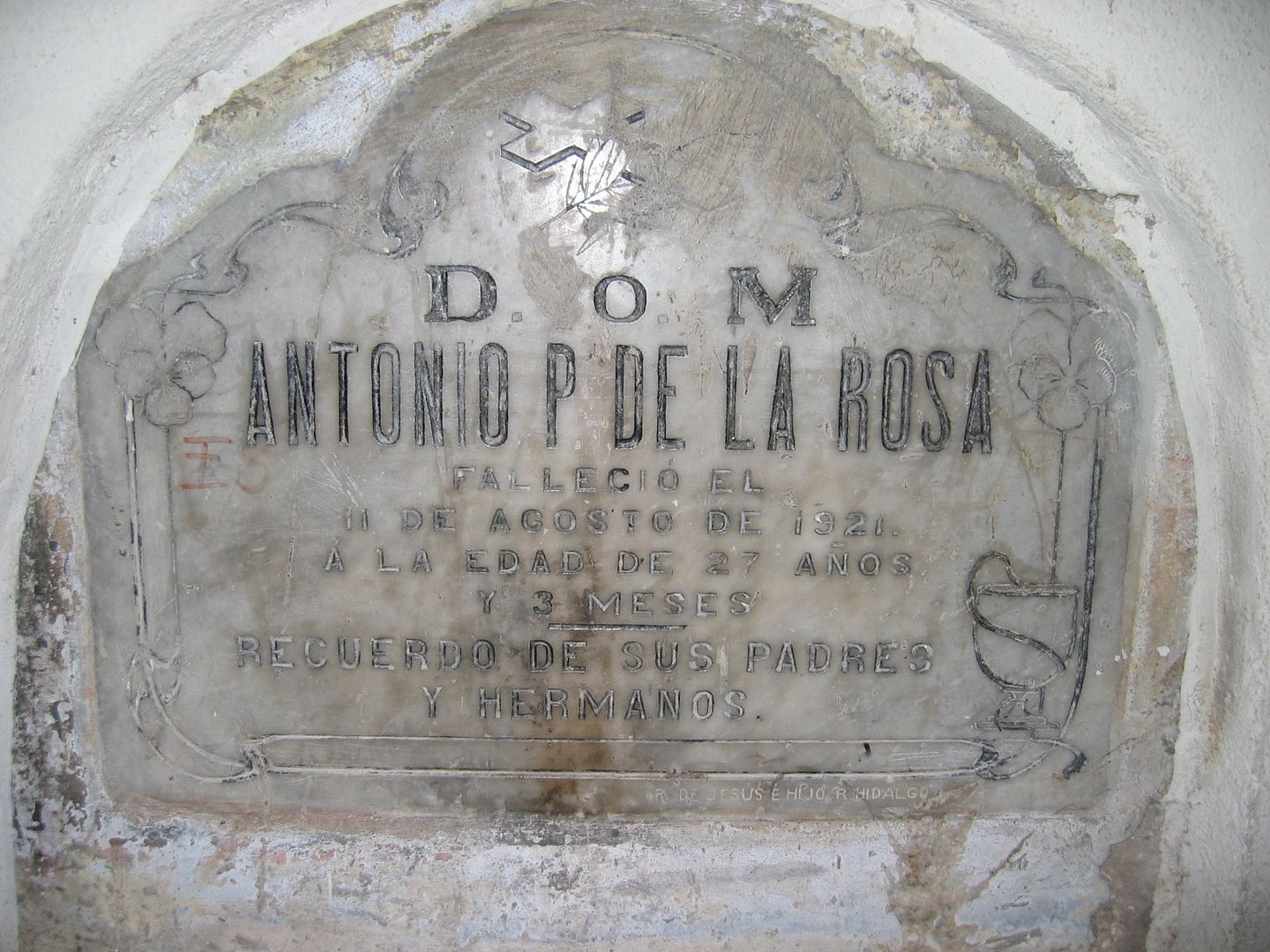

Antonio P. de la Rosa died on 11 August 1921 at the relatively young age of 27 years and three months. His bereaved parents and siblings set up this memorial for him.

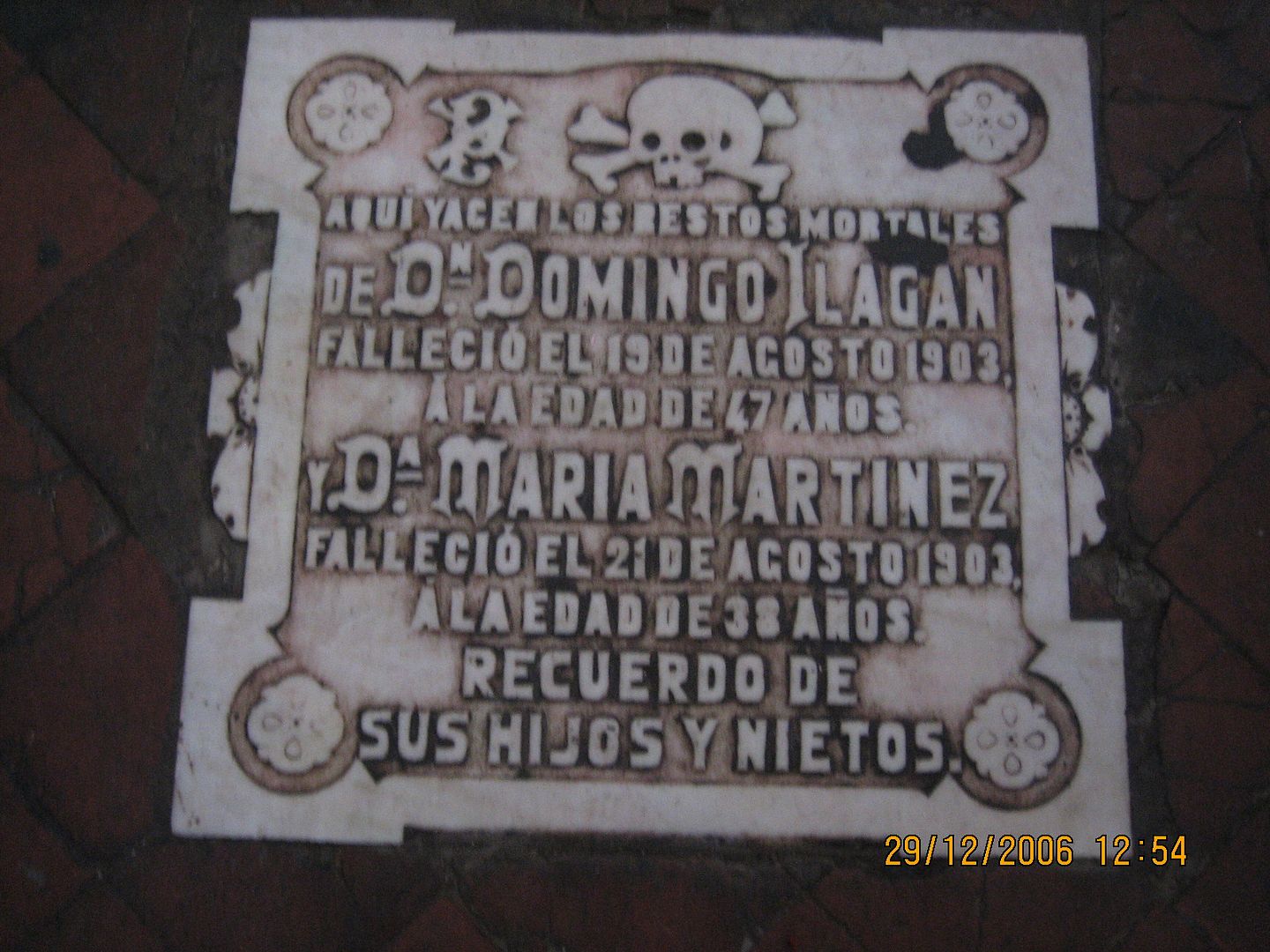

And here set into the basilica’s tiled floor are the remains of Don Domingo Ilagan and his wife Doña Maria Martinez who died just two days apart in August 1903, aged 47 and 38 respectively.

A basilica this large, and with most of its original benefactors now decomposing (or decomposed) beneath the floors, is a real challenge to maintain and keep in tip-top shape in the 21st century, as the observant reader might have noticed from scrutinizing the details in the previous photos.

Imagine if the pious Taal-based sugar barons and shipping magnates of over a hundred years ago were still around, these would not be white-painted pipes pretending to be candleholders in this last photo but silver-plated-brass or even cast-solid-silver candlesticks, the wall in the background would be really white and not just “dirty white,” and the tile floor would be clean, uncracked, and unpockmarked.

We set out for the town, and see if the rest of it is just as well-endowed and hopefully better-preserved.

(Continued here.)

Originally published on 30 July 2009. All text and photos copyright ©2009 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

No comments:

Post a Comment