While I had been to Cebu City about once or twice a year in the previous several years, it was not until January 2010, while on yet another business trip, that I got to visit what has got to be one of the most intriguing heritage structures in the Philippines. I only heard about it shortly before I went on this trip, and my informant, a Cebu native, graciously made arrangements for me to visit it.

It wasn’t all that easy to find. In Cebu’s old Parian (Chinese enclave) district is a maze of ancient streets, one of which is now named Zulueta Street, where stands a nondescript business establishment, Ho Tong Hardware. That sounds straightforward enough, except my totally bewildered cab driver, who seemed to be thinking, “why would this non-Bisaya-speaking alien even want to be in this neighborhood?”, took some time and at least a couple of wrong turns to find first the street, and then the admittedly not-so-easy-to-locate hardware shop, which was my stop.

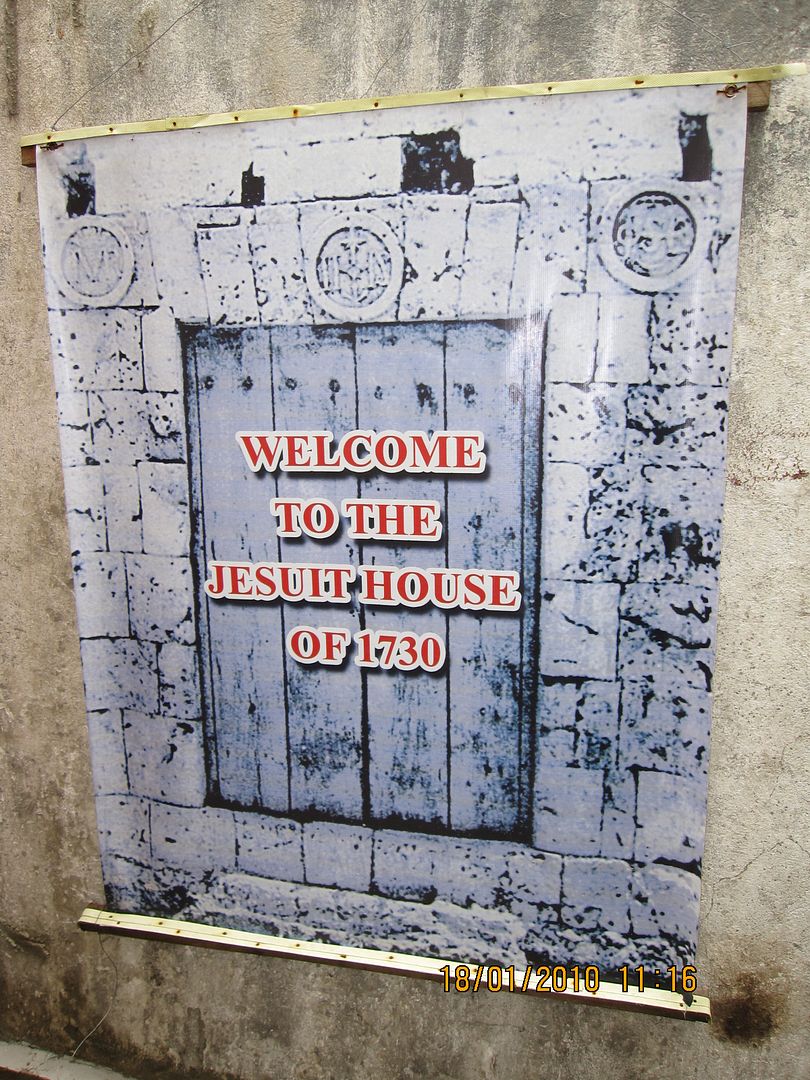

Near the entrance of the establishment was this tarpaulin sign

Near the entrance of the establishment was this tarpaulin sign

I went inside, looked for the office, and introduced myself to the staff, who asked me to wait. In a few moments, the owner-proprietor, who confirmed that he was expecting me, welcomed me in, and led me further into the compound.

We first went past a yard congested with hardware supplies, up into a wooden balcony.

The owner explained that this was the old house’s azotea,

The owner explained that this was the old house’s azotea,

which, at least temporarily, served as the demarcation line between the hardware’s operations and the purported three-centuries-old structure.

which the hardware had further encroached into, it being additional warehouse space for inventories.

Nonetheless, the antiquity of the stone walls and wooden piers was much in evidence, as the owner enthusiastically pointed out.

to the balcony itself, which was tastefully furnished with antique, though likely (or even assuredly) not original, furniture pieces.

From here, one may look out onto the courtyard that we had crossed from the main entrance, now roofed and serving as a huge warehouse.

The balcony was held up by wooden posts, which did not bother to hide their previous incarnations as tall tree trunks when they were still alive in possibly the early 18th century.

At this point, our host gave me a brief backgrounder to the evolution of the house. It was presumed that the Jesuits did live in this compound, and at various times, it might have been a seminary, or a Jesuit-run primary school. When the Jesuits were expelled from the Spanish dominions in the 1760's, the property might have passed to the diocesan authorities. At some later time, it appears to have been privatized and acquired by a Spanish family, who made it their home, and who later on sold it to another family in the mid-20th century, who then set up the hardware business that thrives onsite today.

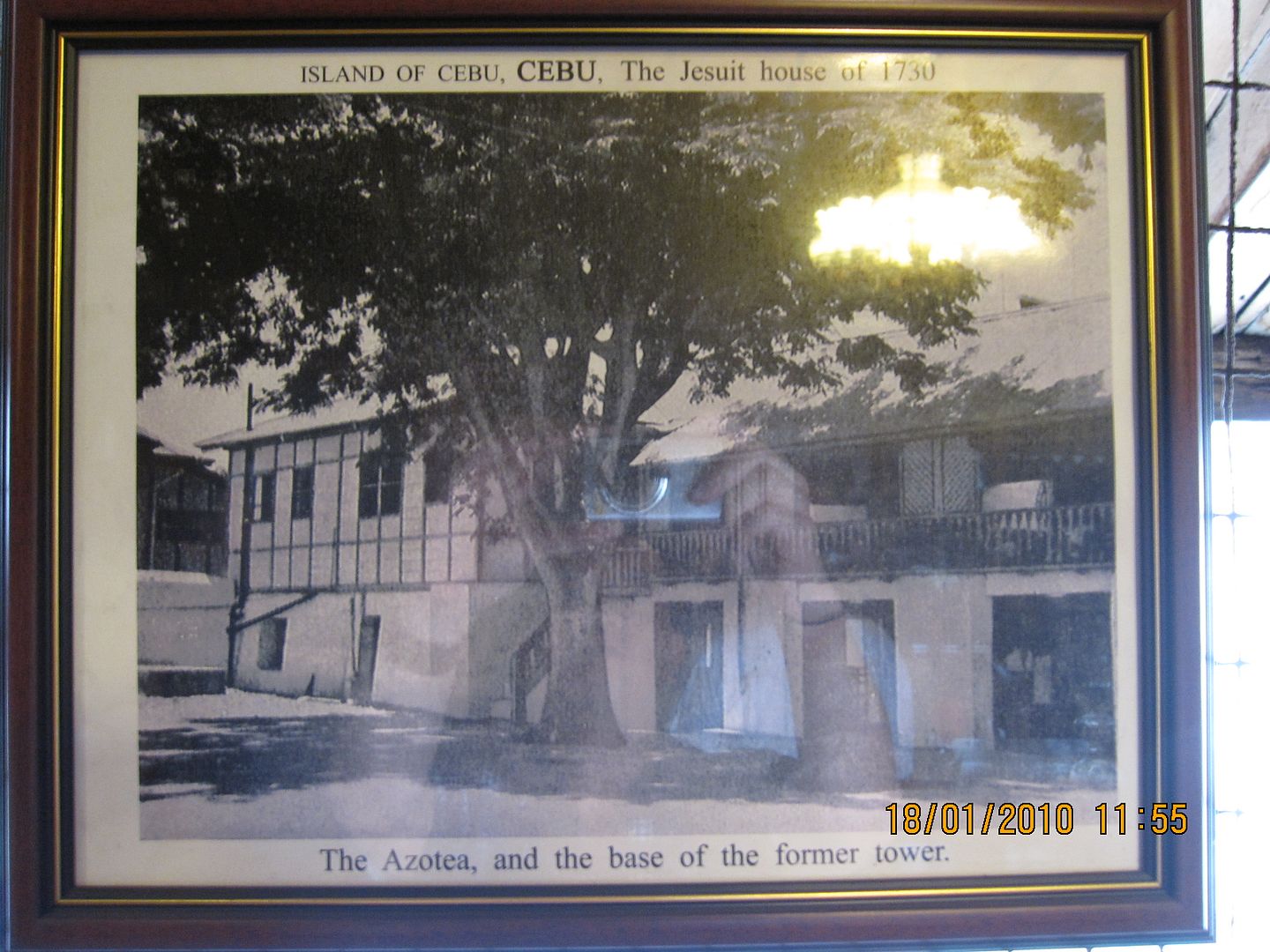

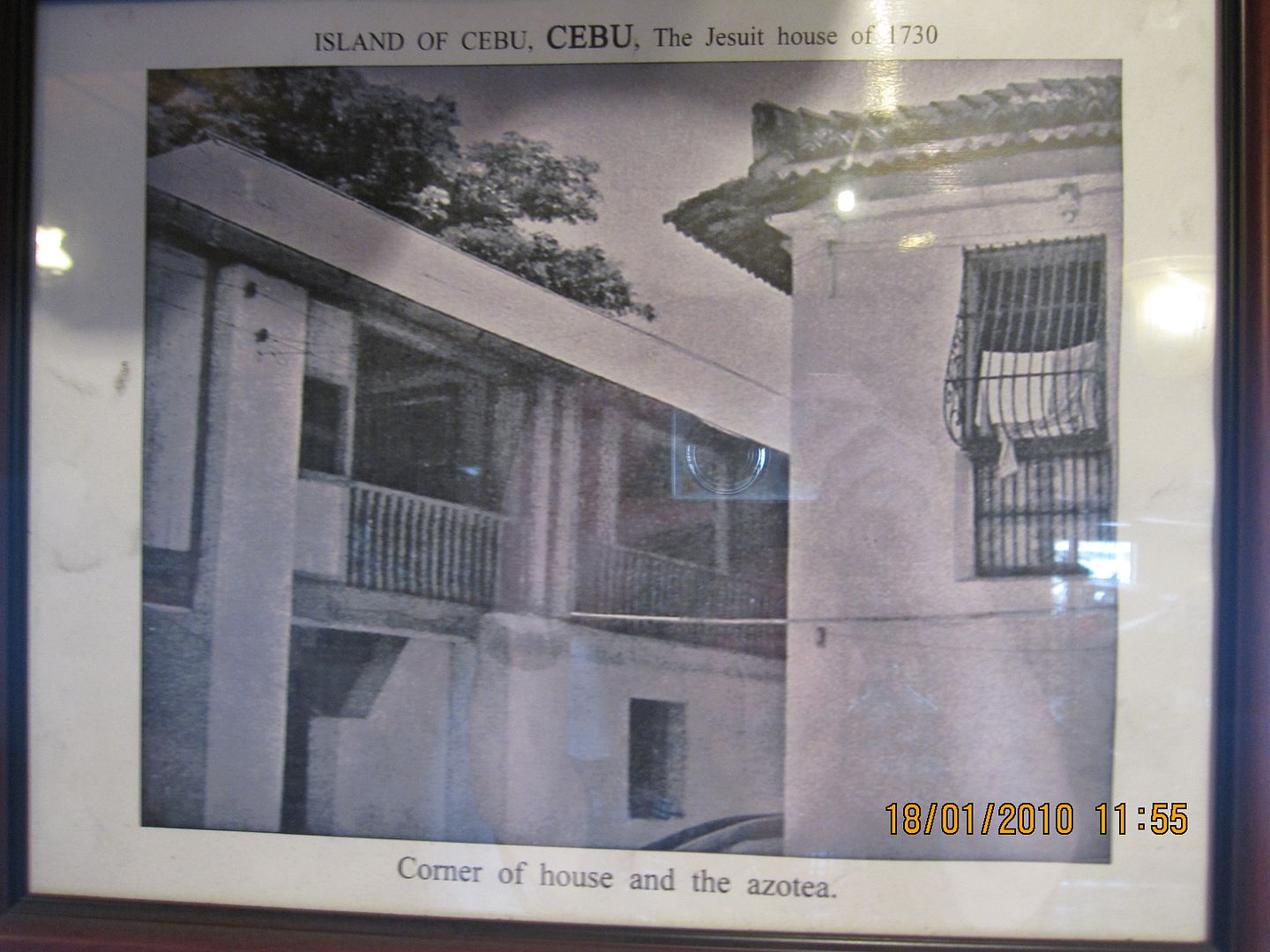

On one of the walls of this balcony were hung prints, reprints of photographs and illustrations made in early 20th century. First was a depiction of the balcony on whose upper storey we now stood, also referred to as an azotea and seen on the right in the photograph.

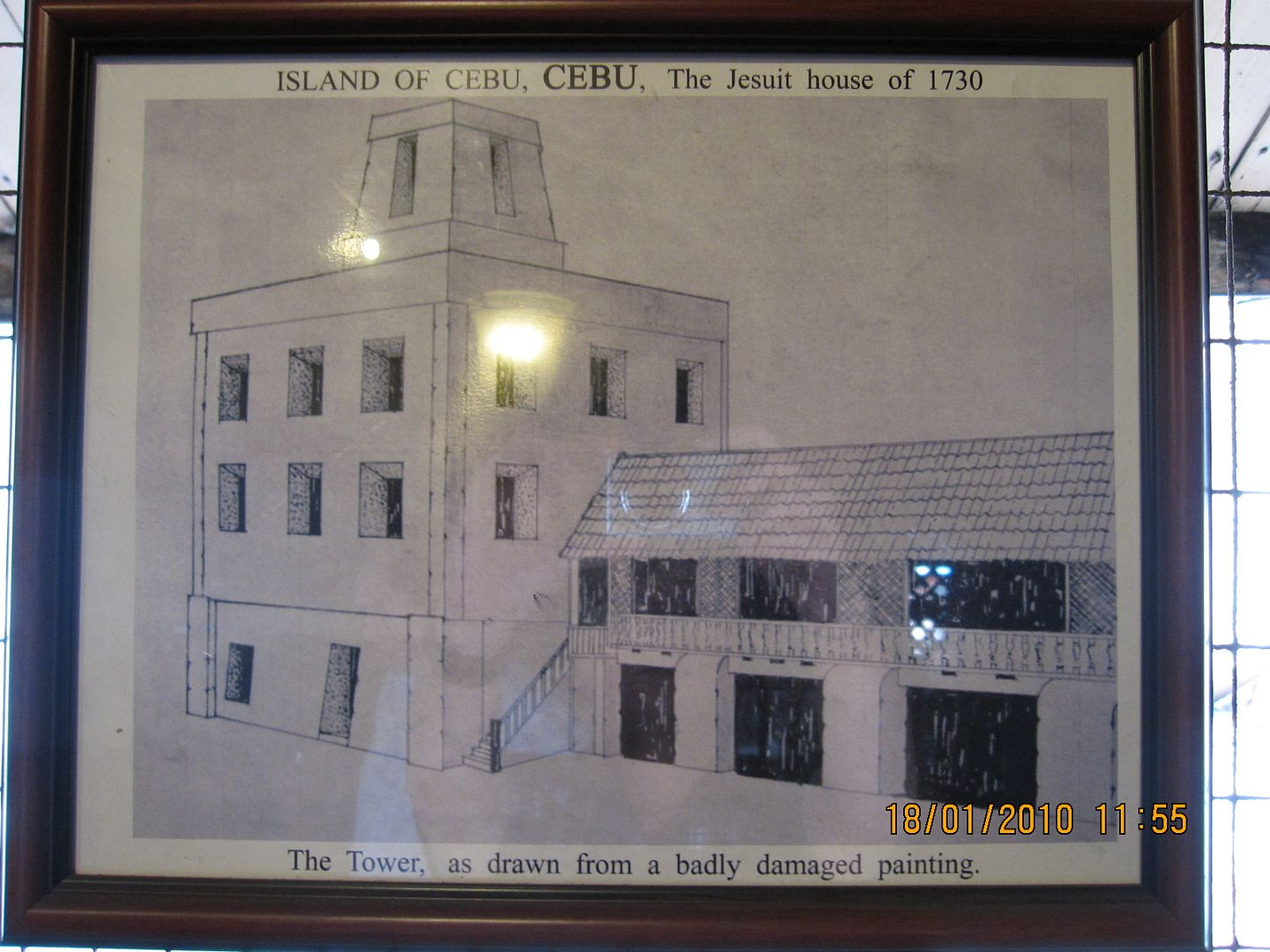

On the left of the photograph beyond the tree (now gone and displaced by the warehouse) was a taller two storey structure. I asked my host what that building was, and he directed my attention to another illustration, this one most intriguing.

On the left of the photograph beyond the tree (now gone and displaced by the warehouse) was a taller two storey structure. I asked my host what that building was, and he directed my attention to another illustration, this one most intriguing.

In this drawing, conjectured from a badly-damaged old painting, the balcony-azotea was still there on the right, but on the left was a formidable-looking four-storey stone tower.

Clearly, at some point around three centuries ago, what adjoined the azotea was that massive structure, which, by the early 20th century had been reduced to just two storeys, the upper one no longer of stone but of lighter materials, as the first photograph had shown. That would explain why it had been described there as "the base of thee former tower."

Sufficiently made curious, and explaining, by way of an excuse, that I was a fan of all-stone structures, I inquired as to the possibility of exploring whatever remained of that tower. My host led me down the length of the balcony, down a small passageway,

and into a large empty space

and into a large empty space

A corner of this vestige of the tall stone tower had a view into what appeared to be yet another separate structure.

That window across looked familiar, I thought. And then I recalled that back in the balcony was a third large print, showing that kind of a window

That window across looked familiar, I thought. And then I recalled that back in the balcony was a third large print, showing that kind of a window

Sensing my increasing wonder at the multiplicity of structures and how they related to each other, my host led me back to wooden balcony

and pointed out a path that led across a very short connecting passageway,

and pointed out a path that led across a very short connecting passageway,

actually the living room of the “house” referred to in the third framed illustration back in the balcony.

That does look like “1730,” doesn’t it? Of course, one wonders why it would be inscribed on an interior wall of the house rather than on the outside. Hmmm.

Before I could ask my next question, my host asks me to follow him to the far end of the living room, down the main stairs, and out onto the back street.

but this, today called Binakayan Street, was the original main entrance to the house, now much obscured and marked simply by a red metal gate punched through one gray wall.

The gate’s grilles have been extended upwards to provide some protection to the original stone carvings above the passageway.

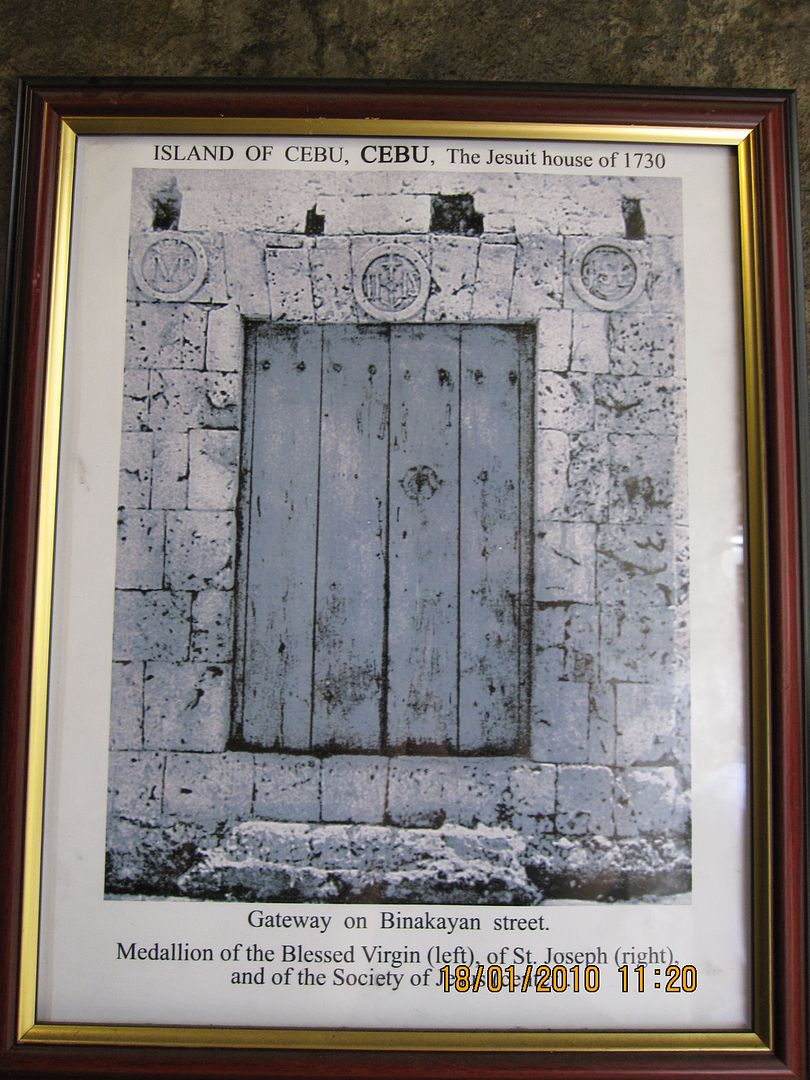

Another framed copy of an early 20th century photograph shows how the getaway looked at that time, identifying those stone carvings as medallions of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph, and the Society of Jesus itself.

We do as visitors to the Cebu Jesuits might have done in the 1730’s, and walk through the wooden doors, now embellished with a small angel.

And to remind modern-day visitors that this was the original main entrance, another tarpaulin has been hung just inside the gateway, using the old photograph as the background.

From within the entrance courtyard, the visitor may appreciate the house’s still-plastered ancient stone walls,

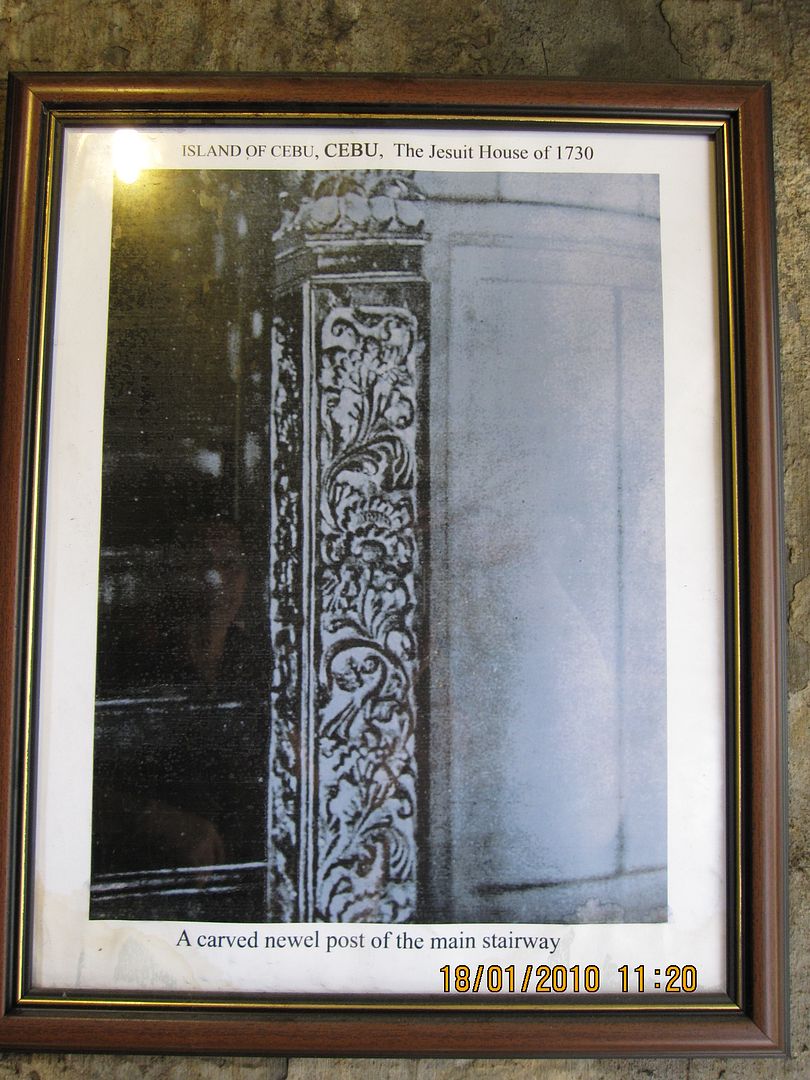

Entering the ground floor, near the foot of the main staircase,

one appreciates more original construction details, such as these heavily carved corbels.

where more original architectural details may be noted,

sometimes by their absence.

The structural details of the interior appear to be an amalgam of various styles and construction techniques,

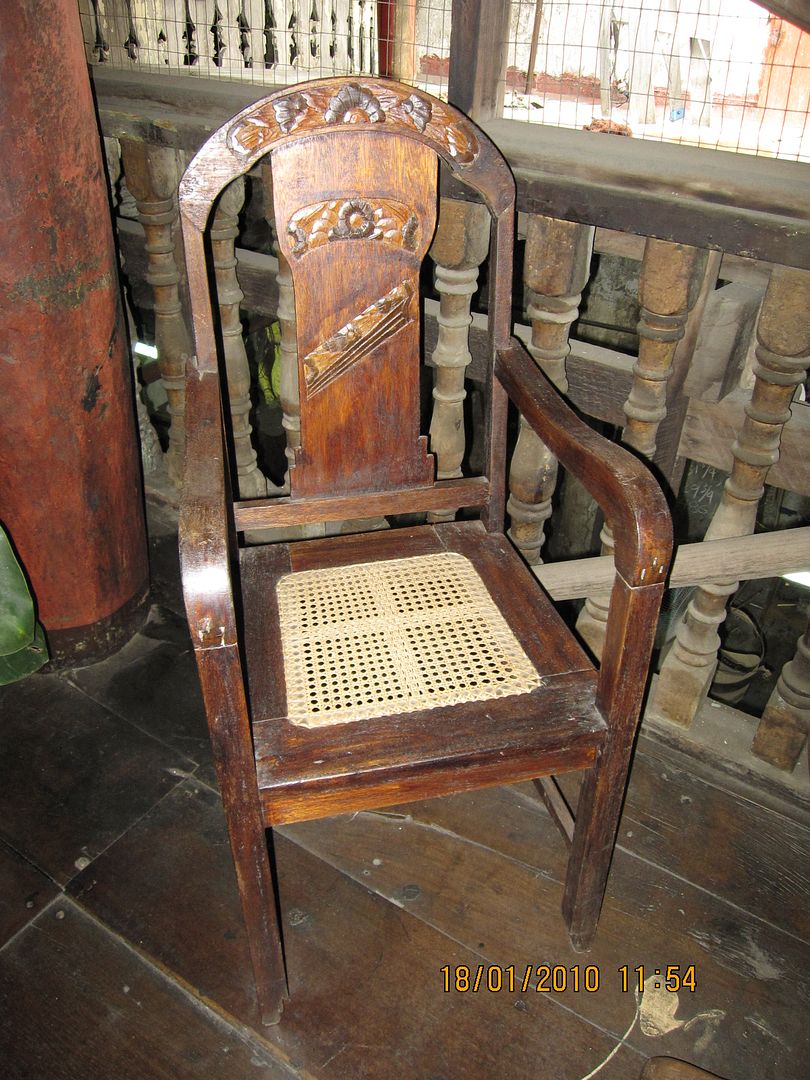

Back in the large living room that we passed through earlier before going out to the original main entrance, we note that, like the balcony that we entered at the start of this visit, it is furnished tastefully with antique, though likely not original, furniture, including this butaca,

this Gothic-style comoda,

a pair of armchairs that would not have looked out-of-place in an 18th century Visayan church altar,

a large altar table on which were placed an antique urna, a pair of oil lamps, and small religious images,

a pair of lounging chairs flanking a baul (chest) on which is positioned an early 20th century sewing machine.

and other late 20th-century renditions of what 19th century Spanish colonial furnishings must have looked like.

This large living room’s floor consisted of planks of alternating dark- and light-colored hardwoods, likely balayong and molave,

and overhead was a three-armed reproduction antique lamp in the style most familiarly known as “Dutch wrought-iron.”

which enabled us to observe other peculiar construction details, including tall and wide windows with upper and lower portions,

and higher original ceilings concealed by lower “false” ceilings added later,

indicating that the original ceiling height throughout this main floor was significantly higher than at present,

and which could be reinstated in the course of a future restoration.

where we could sit down and prove that a three-century-old structure may still welcome modern-day humans just slightly less ancient than itself.

Many thanks to my hosts, Mr. Jimmy Sy of Ho Tong Hardware and Casa Jesuita, Architect Anthony Abelgas, and Mr. Louie Nacorda (who kindly provided that last photo).

Originally published on 5 February 2012. All text and photos (except where attributed otherwise) copyright ©2012 Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Original comments:

Original comments:

johnada wrote on Feb 12

I like the hardware store part, lol. It prevents the house from looking museumified and artificial that I see in so many houses, hahaha

|

rally65 wrote on Feb 12

johnada said

I like the hardware store part, lol. It prevents the house from looking museumified and artificial that I see in so many houses, hahaha

Actually the good part is that the owner / hardware store proprietor is a heritage enthusiast, who is keen to balance the commercial value of the (rear part of the) property (the large hardware store) with the three-hundred-year-old heritage structure on it.

|

anen21999 wrote on Feb 13

I have not been here. But when I was in Cebu I went to the Yap-Sandiego house which dates back to 1675, said to be the oldest.

|

rally65 wrote on Feb 13

anen21999 said

I have not been here. But when I was in Cebu I went to the Yap-Sandiego house which dates back to 1675, said to be the oldest.

I have been to both houses. The only thing clear is that the title is in dispute.

|

epotenciano wrote on Feb 16

Like all your posts here, been a fan of this site !!! Nice work !

|

rally65 wrote on Feb 16

epotenciano said

Like all your posts here, been a fan of this site !!! Nice work !

Thanks for the visits and the appreciation!

|

antonmg wrote on Sep 2, edited on Sep 2

Sadly, the house is in such a poor state. Being the owner of the hardware, he can very well restore the structure if he really wants to preserve this piece of 1730 heritage. The long gone Jesuits who used to lived there might be mortified at its present state. This once glorious and noble house now looks like a slum dwelling. Older houses in Spain and Mexico restore structures to close to its original state (not necessarily to its original use, like a church could be restored but no longer used as a church and turned in to a library for instance). This house is sadly, dilapidated and decrepit.

The saving grace is that the owner did not decide to tear it down. Congratulations to him! But he kept it "as is" only, and did not make obvious attempts to restore it. He further ruined it with chicken coop grills and that horrible gate "to protect the carvings above". It needs a paint job badly. A much needed "hilamos" or white wash. Grills removed, broken window panes and roof tiles replaced, rotten wood patched up... and graffiti removed. The tree saplings growing in the cracks above the portal carvings have to be removed as the roots will eventually destroy the carvings and eventually they will fall off. These have to be removed right away. The furnishings are the owners prerogative. The present use of the structure as a hardware is not the most ideal but there is nothing wrong with it either if the owner wishes to use it as so. This is a constructive comment and is not meant to be mere criticism. I am an Atenean, Jesuit-schooled since my formative years, and eventually given a degree in architecture by the Dominicans of UST. I am a great admirer of the Society of Jesus. And just like many of your readers, I am a staunch supporter of hispano-philippine art and history. |

rally65 wrote on Sep 2

Thankfully, the owner is an advocate of heritage preservation as well, and at the time I visited, was trying to figure out ways to further preserve and restore the structure, including relocating the hardware if possible. I have not been there again since I visited in early 2010, but I was told that the preservation program has progressed -- perhaps others who have can tell us what changes have been made in the past two years.

|

antonmg wrote on Sep 2, edited on Sep 2

I am delighted to hear of an on-going restoration program. Hopefully, for history's sake, a proper and academic restoration. It is imperative that the pastiche is removed along with the plastic roofing.

On the other hand, I am suddenly curious to see where the 1730 insignia lies. They are normally located on the exterior walls. Perhaps in this case there may have been some expansions made in later years due to the arrival of more Jesuits decades later. These structures are usually set back from the street. Sometime later it may have been expanded towards the street thus explaining the 1730 eventually being located inside the house. I would love to find the clues to that, the foundations and beams will be the silent but tell-tale signs of after thoughts. How interesting..... thank you for this 1730 Jesuit House posting. It made my Sunday morning even more delightful. |

rally65 wrote on Sep 2

You should make a personal visit to the Casa Jesuita. Send me an email (leo_cloma [at] yahoo.com] so that I can give you the owner's contact details. You can then make an appointment to go.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment