“To sing is to pray twice” wasn’t lost at all on the ancients – it is sometimes easy to forget that the Old Testament has a fair number of examples of musical material, from the obviously-titled Song of Solomon (also called the Song of Songs) to the Lamentations of Jeremiah (better sung than wailed). Our clear modern-day favorites are the Psalms. The ancient Greek word meant “songs sung to a harp,” but harpists were not always readily available throughout the past three-odd millennia, so since two thousand years ago, “psalms” simply became synonymous with “songs.”

Traditionally, the Psalms are attributed to King David (of David and Goliath fame), who is said to have based his song-writing output on the works of earlier “psalmists” including Adam and Moses. Since we don’t have any of Adam’s or Moses’ songs on-hand, it is difficult to say just how closely David copied his forebears’ styles. Which is just as well, I suppose.

In reality, even though about half of the one hundred and fifty numbered Psalms include David’s name, they are all most likely the work of several authors, or groups of authors. Since they weren’t formally written down in Hebrew until nearly half a millennium after King David reigned, they must have relied on recited and / or sung transmission of any materials actually originating from David.

Psalms have always been in use for worship throughout Christian history. The Holy Mass always includes a Responsorial Psalm, which is nothing but a rearrangement of the Psalm texts into verses with an antiphonal response from the congregation. This is often sung, though you’d be lucky to have a good cantor to sing the verses and a good song leader to teach the congregation how to sing the response properly.

There are also many musical arrangements of the Psalms, in English, Pilipino, or other Philippine languages, in current use throughout the

We now look at a sampling of different Psalm settings, from other musical traditions, starting with “Anglican Chant.” This refers to the practice in the Church of England (i.e., the church originally established by Henry VIII to break-away from the Roman Catholic Church) of chanting the Psalms to English texts, using a simple harmonized melody in seven, fourteen, twenty-one, or twenty-eight bars. The precise melodies and harmonies evolved from the 16th century onwards, but were probably pretty much established by the 18th century, and were fully developed in the Victorian era, with chant settings authored by distinguished English composers in the 19th century, as we’re about to hear.

First is a setting of Psalm 84, “O how amiable are thy dwellings” with a chant composed by Sir Hubert Parry (1848-1918). This is from the album “The Sound of King’s,” (EMI CDZ 7 62852 2) an anthology of choral works performed by what many say is the world’s best choir, the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge.

Here is a recent photograph of the choir in their home chapel in King’s College, a famous structure with acoustics that make them sound even better than they already do to begin with.

In their rendition of Psalm 84, which dates from 1969, they were led by their then Director of Music, the venerable Sir David Willcocks, who retired in 1974, but is still an active musician to this day.

The choir recorded all one hundred fifty Psalms in Anglican Chant during Mr. Willcocks’ tenure there, with him usually playing the small accompanying pipe organ. This allowed the choir to demonstrate various variations of Anglican chant – including where verses are sung alternately by the higher voices (boy sopranos and male altos) and by the lower voices (tenors and basses), or by half of the choir (half of the sopranos, altos, tenors, and basses), and then by the other half.

As a matter of fact, choirs in Anglican churches are usually positioned into two halves straddling the nave of the chapel or church, with the halves referred to as “cantori” (the half positioned on the cantor’s side) and “decani” (the half positioned on the dean’s side). So depending on the chant arrangement used, one could achieve a “stereophonic” effect with volume increasing or decreasing, and shifting from left to right to center. I recommend listening to their recording of Psalm 84 again and try to see what dynamics were used by the King’s College Choir with Parry’s chant arrangement.

After Mr. Willcocks retired, he was succeeded as Director of Music by Sir Philip Ledger, who also made many recordings with the choir.

From these two tracks, one may observe that despite the gap of nearly a decade and the leadership of two different conductors, the choir’s sound has not changed at all. It is indeed paradoxical that despite the fact that the choir’s membership constantly changes – the boys’ voices break and therefore trebles usually stay in the choir for no more than three years, and the choral scholars leave the choir after graduation from the university – the choir sounds exactly the same from year to year. Just another example of how a religious musical tradition is transmitted through the ages – perhaps directly, in a manner of speaking, from old King David himself!

The current Director of Music at King’s College,

He too has recorded prolifically with the choir. In the album “The Sound of King’s” cited earlier, there is a recording of “Miserere mei, Deus” (Have mercy on me, O God), made in 1984, not long after Mr. Cleobury took over. This piece is a setting of Psalm 51 composed by Gregorio Allegri (1582-1652), priest, composer, and member of the Sistine Chapel Choir in

(A 1987 version of the piece conducted by Stephen Cleobury by the King's College Cambridge)

(Another version of the piece)

The well-known story about this piece is that to preserve its exclusivity, the church forbade copies from being published. That changed when the fourteen-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, visiting

Psalm 51, “Miserere mei, Deus”

Miserere mei, Deus,

secundum magnam misericordiam tuam;

et secundum multitudinem miserationum tuarum,

dele iniquitatem meam.

Amplius lava me ab iniquitate mea,

et a peccato meo munda me.

Have mercy on me, God,

in accordance with your great mercy;

and in accordance with the greatness of your pity,

destroy my wrong-doing.

Furthermore, wash me of my wrong-doing,

and cleanse me of my sin.

In reality, this is an abridged version from the original recording, and includes only verses (stanzas) 1 to 4 and 17 to 20. There are several famous recordings of this venerable work truly worth dipping into, with perhaps one of the first all-time classical lollipops being a recording made, in an excellent English translation, by the Choir of King’s College,

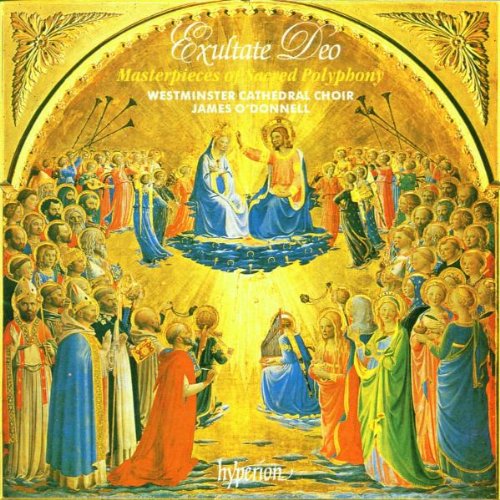

If you want to listen to Allegri: Miserere in the original Latin, the best recording that I have listened to is the one by what I think is the best choir in the world (despite what the King’s College Choir fans might say) – the Choir of Westminster Cathedral in London. This is the major Roman Catholic Cathedral in the UK, so I’m probably biased on at least two counts: (1) I’m a Roman Catholic, and (2) I’ve actually attended Sunday High Mass in the Cathedral with the choir on hand on a few occasions. But I’m not the only one who thinks they’re outstanding – they are among the most awarded choirs in the world, with Gramophone Awards received for some of their recordings, and they continue to sell plenty of CDs of their recordings, of which they make frequently.

(a recent recording of the piece from the Choir of Westminster)

Credit must likewise go to the choir’s Master of Music, James O’Donnell, who joins a distinguished roster of choir directors since the Cathedral was founded about (only!) a hundred years ago.

Interestingly, Stephen Cleobury was Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral prior to moving to King’s College, Cambridge

Again, their Allegri: Miserere lasts nearly twelve minutes. I do strongly recommend the album that it comes from: Masterpieces of Sacred Polyphony; Westminster Cathedral Choir, directed by James O’Donnell. This was recorded in 1995 and is published as Hyperion Records CDA 66850. The last track in that album is a six-voice choral setting of Psalm 97, “Cantate Domino,” composed by the late renaissance-to-early baroque composed Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643).

Cantate Domino canticum novum,

cantata et benedicite nomini ejus,

quia mirabilia fecit.

Cantate et exultate et psallite,

psallite in cithara et voce psalmi,

quia mirabilia fecit.

Sing to the Lord a new song,

sing and bless his name,

for he has done marvelous things.

Sing and rejoice and sing praise,

sing praise with the lute and with the sound of a hymn,

for he has done marvelous things.

This joyous setting, perfectly matched to this very popular Psalm’s message, is most exuberantly delivered by Mr. O’Donnell’s full-throated boys (sopranos and altos) and men (countertenors, tenors, and basses) in the expansive acoustic of the Cathedral. To my ears, this piece is a short (two-and-a-half minute) but solid demonstration of why this is the best choir in the world.

Have another listen and see if you don’t agree that they make old King David proud. And the Lord Himself as well, no doubt.

Originally published on 18 March 2007. Text copyright ©2007 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted. Musical examples are owned by their respective copyright holders and are used only for review and demonstration purposes.

No comments:

Post a Comment