It’s always difficult to determine when specific pieces of furniture were actually made – after all, they aren’t usually signed and dated like paintings or other works of art. Some aparadors are known to have been near-conclusively dated while undergoing restoration – from original newspapers that were used as lining in between the mirror and the wooden panel of the door interior, but I don’t think that owners would fancy letting me pry open their aparador mirrors just to see if there may be any yellowing “La Solidaridad” issues inside that might help us date their pieces.

So for the most part, a safe, convenient, usually acceptable, though not entirely accurate method for dating aparadors is to do so using stylistic cues. In the previous article, for example, we focused on aparadors that “looked” like they were made in the late 19th century or earlier; we checked if the overall style was Classical, Gothic, Baroque, Victorian, or Art Nouveau, and since these styles were common in the 19th century, we made the inevitable conclusions. For others, we noted the absence of mirrors, and, because mirrors used to not be so widely available in the Philippine Islands, we took that to mean that the piece was likely old.

In reality, though, styles tended to overlap, and older styles continued to be produced even in latter periods. Remember the brand new freshly-made reproduction Gothic-style aparador we saw in the previous article?

Even when mirrors became more widely available, some patrons still preferred their aparadors to be mirror-less. (No doubt, the influence of Chinese geomancy is evident here, as mirrors in bedrooms are considered to be bad feng shui.)

So for the most part, a safe, convenient, usually acceptable, though not entirely accurate method for dating aparadors is to do so using stylistic cues. In the previous article, for example, we focused on aparadors that “looked” like they were made in the late 19th century or earlier; we checked if the overall style was Classical, Gothic, Baroque, Victorian, or Art Nouveau, and since these styles were common in the 19th century, we made the inevitable conclusions. For others, we noted the absence of mirrors, and, because mirrors used to not be so widely available in the Philippine Islands, we took that to mean that the piece was likely old.

In reality, though, styles tended to overlap, and older styles continued to be produced even in latter periods. Remember the brand new freshly-made reproduction Gothic-style aparador we saw in the previous article?

Even when mirrors became more widely available, some patrons still preferred their aparadors to be mirror-less. (No doubt, the influence of Chinese geomancy is evident here, as mirrors in bedrooms are considered to be bad feng shui.)

With these caveats in mind, we continue our march into the 20th century, with aparadors that just MIGHT be from the early American Colonial period.

Feng shui or not, most people I know simply love mirrors. Oval-mirrored aparadors were rare and are today sought after for the use of ladies, young and old. Here’s a single-door model with floral wood inlay:

Here are three more:

Here are three more:

And if the lady in question is a bit on the, er, voluptuous side, here is something that might be appropriate:

Some patrons still preferred carving to inlay, so oval-mirrored aparadors were turned out this way:

And here’s the version for our plus-sized lady:

As we’ve seen before, sometimes, small mirrors were used as accents for the crown. The small oval mirror on top of this one echoes the large oval mirror on the door.

These next two take the easy way out and use small round mirrors on top even if the large mirrors are oval:

While this one couples an oval mirror on the door with an unusual shield-shaped mirror on the crown:

And just when you think you’d had your fill of oval-mirrored aparadors, what about DOUBLE-OVAL aparadors, i.e., two-door aparadors, and both doors with oval mirrors? Here’s one with subtle wood inlay:

Here’s one with carvings around the mirrors:

Here’s a double-oval with a small round mirror on the crown:

This last double-oval grandly combines an elaborately carved crown with a small oval mirror:

This next aparador seems rather ordinary at first glance, until one notices that the corners are chamfered (set at a diagonal) – I haven’t seen any others of this type.

Apart from carvings and floral wood inlay of the type that we’ve already seen, a popular and frequently seen method of ornamentation involved the use of tiny pieces of light- (lanete) and dark- (kamagong) colored woods arranged in a frieze along the outlines of the aparador. This was then topped with a diamond shape with an inlaid flower within. Here is a typical example:

This is today labeled the “Puyat style” – referring to the eponymous Manila-based manufacturer and marketer of wooden furniture during the American colonial period – mass-produced pieces then, valuable antiques now. It is unclear if the Puyat factory was the originator of this style of inlay; what was certain is that it wasn’t the only one decorating their products this way. Here are more examples of this style, starting with this one with a bowl of fruit on the crown:

The chimney / unicorn theme seems to have been a popular partner to the Puyat style of inlay. Here it even gets wood-inlaid garlands and an inlaid monogram:

What about a near-identical pair of oversized single door Puyat-style aparadors?

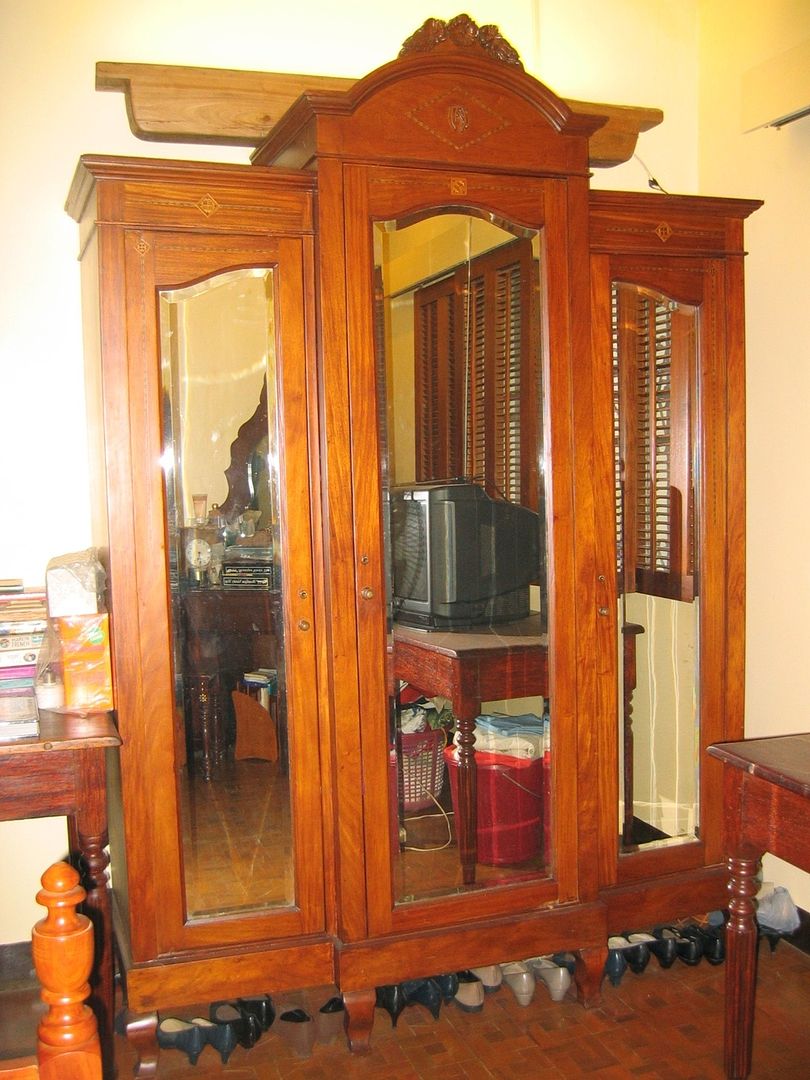

Here’s the ultimate Puyat-style aparador – a one-of-a-kind three-door specimen.

(For the observant and curious, that long thing on top is actually an antique “labangan” [a feeding trough for animals], now used as a fluorescent lamp holder for indirect lighting.)

Mirrors themselves also got their own ornamentation, as can be seen from this original example:

Here are two more:

If one couldn’t decide whether to have mirrors or not (should one follow the feng shui expert’s advice, or give in to one’s vanity?), how about a way to conceal the mirror when it’s not in use (i.e., when we’re asleep)? This next one has an unusual canvas-backed wooden tambour screen that slides down over the large rectangular mirror, and slides up and behind when the mirror needed to be exposed, much like the sliding cover of a rolltop desk. (Unfortunately it had not been restored when this photograph was taken, so you’ll have to take my word for it.)

If oval-mirrored aparadors were usually for ladies, some gentlemen nonetheless tried to have them also. The variation for men was what is now referred to as the “caballero” aparador. I don’t know what this has to do with horse riders, or if cowboys really preferred this style, but its structure – single-door aparador on one half, and a man’s chest of drawers with a small mirror on the other half – might be vaguely horse-like, I guess. Here’s one where the small mirror is also oval (unfortunately obscured by an antique crucifix), just like the one on the aparador:

This next caballero has, predictably enough, two rectangular mirrors – one large and one small.

And this one has arched mirrors – again, one large and one small.

Finally, here’s one that disobeys the rules, with a large oval mirror and a rectangular small one. What a spoiler!

These caballero aparadors partly demonstrate the transition to the second half of the American colonial period, as we will see next.

mike10017 wrote on Dec 12, '06

caballero is gentleman as in damas y caballeros(ladies and gentlemen). Aparadores would probably be the most common piece of antique furniture in the Philippines. Almost every family has their lola's aparador hiding in some corner of the house. Especially in the provinces this is as ubiquitous as the ambassador set in your earlier posts.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment