After that Sunday morning in Malaybalay and lunch back in my base in Cawayanon, in Bukidnon province’s Manolo Fortich municipality, I headed off on a one-and-a-half hour drive to the town of Balingaság, a coastal town north of Cagayan de Oro city on Macajalar Bay, in the neighboring province of Misamis Oriental.

Curious readers will scratch their heads and wonder what the big deal is about going to this never-heard-of place, in an obscure part of the Philippine archipelago. In truth, Balingaság must have been among the wealthiest port and fishing towns in Northern Mindanao in the Spanish colonial period, sustained not only by its seaside location but also by the forests and agricultural lands around it that yielded timber, copra from coconuts, and a host of other crops besides.

With the ascendancy of Cagayan de Oro as the premier city in Northern Mindanao in the American colonial and especially postwar periods and the shift of transport and commercial hubs away from Balingaság, the old town became less well-trodden and more obscure, to the point today where only people from the surrounding region might have heard of it – with me perhaps being one of the few exceptions.

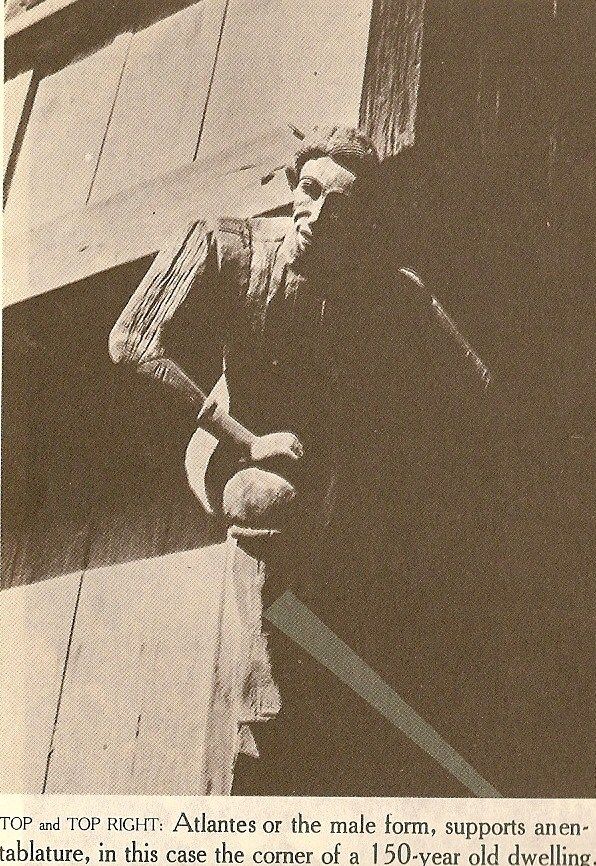

And yet again, I must credit my fake-knowledge of this Akyat-Bahay Gang destination to Zialcita and Tinio’s Philippine Ancestral Houses, published in 1980. For buried within this venerable volume was this curious photo

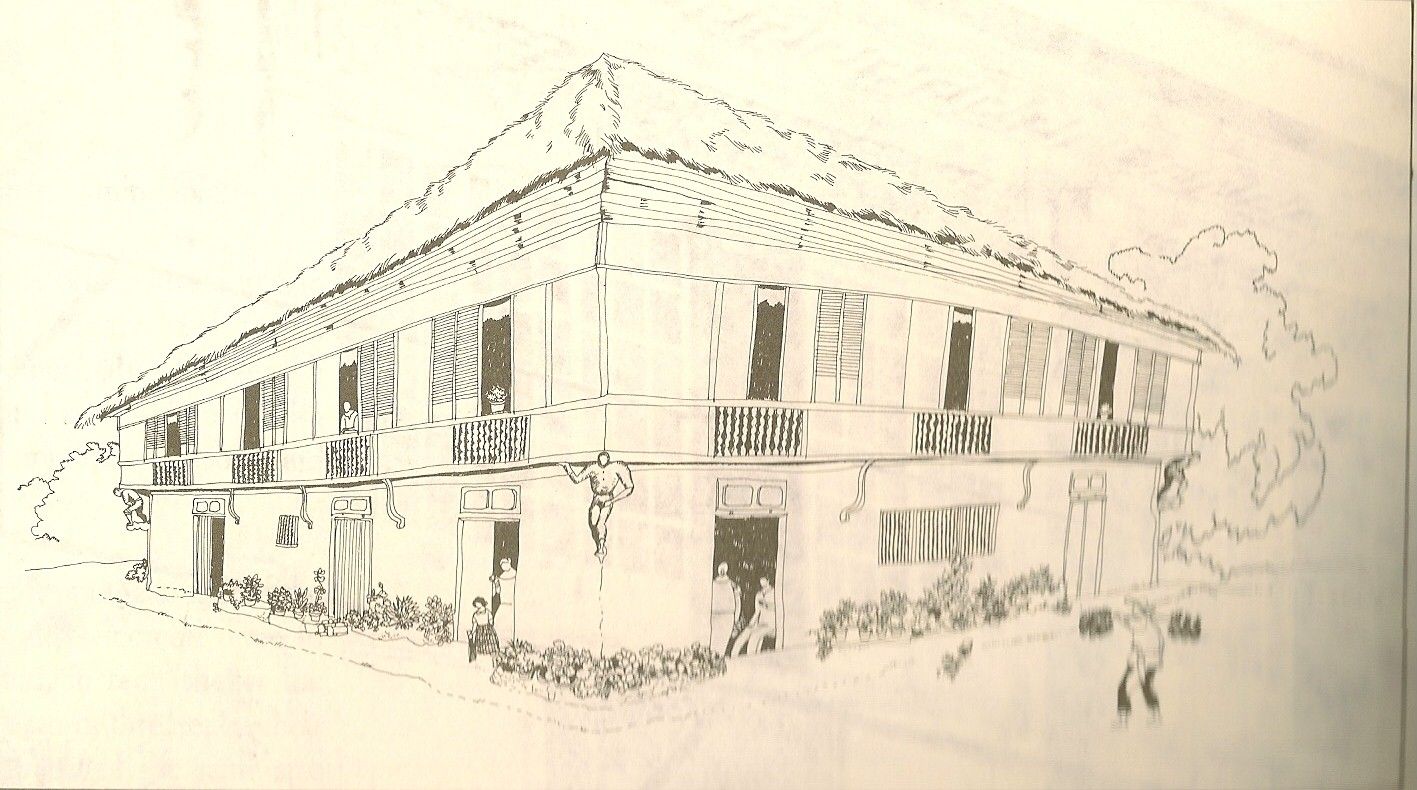

And right beside it was this drawing of the impressive structure from which the photo was taken.

The photo credits listed the house as the “Jimenez House in Balingaság, Misamis Oriental.” I had kept a mental note of this over the years, and resolved to visit the first opportunity I got. And that finally came that Sunday afternoon after Malaybalay.

Because it took a fair amount of planning and effort to get there, I was hoping that Balingasag’s 19th century wealth had allowed its then townspeople (Christian settlers mainly from the Visayas) to amongst other things build large and comfortable homes well into the early 20th century, and that the town’s subsequent obscurity had somehow preserved them for heritage junkies like me.

I’m pleased to report that overall, this hypothesis was proven correct, for after making a few inquiries from the locals in the grid-laid-out center of town, I beheld this:

I admit that the feeling was akin to that of some demented Templar finding the Holy Grail. At least the demented part.

The first thing I inspected were the “atlantes” or male sculptural forms that held up the corners of this huge house and that had caught my attention long ago while reading Philippine Ancestral Houses. Contrary to my expectation, only three of the four corners were so supported – because the fourth corner (on the extreme right in the following two photos) was in the backyard (rather than on two of this town’s main streets) and would not anyway be appreciated by the pigs and chickens back there.

The other reason that there were only three such “supporters” is that they supposedly represented the three only offspring of the house’s original owner from early in the 19th century, Don Faustino Vega. As such, here we might have on the leftmost corner of the north-side elevation an intended representation of eldest son Señor Crispin Vega (its left arm now reportedly in a museum in Cagayan de Oro):

At the junction of the north-side and west-side elevations is middle son Señor Eusebio Vega’s stunt double.

And finally, youngest son Señor Melquiades Vega’s stand-in brings up the corner on the rightmost side.

Another view of this immense house shows Eusebio at the extreme left and Melquiades in the center of the photo.

And they’re not just ordinary sculpted figures, but life-sized ones even, as seen in this shot where Eusebio seeks help from the adult human standing beneath him.

Sadly, Melquiades looks over a barbed-wire fence and can expect no such human support.

The segments in between the human-figure-supported corners were ornamented by apparently non-load-bearing but beautifully carved wooden brackets.

The ground floor of this nearly-two-century-year-old home was unusually welcoming, with three wide-open sets of double doors on two side elevations, and two more that were closed but that could easily be opened if needed. The door panels were tall too, and were surprisingly close in appearance to their late 18th and early 19th century contemporaries in Luzon.

The welcoming feeling was no doubt due to the fact that the ground floor, which originally would have been a series of storerooms for the family’s agricultural produce, was now an enterprising diner.

It being mid-afternoon already, I had just missed the lunch crowd.

But the happy hour gang later will have this modest bar at their disposal.

The gracious proprietress turned out to also be the mistress of the house, so I sought her permission to visit their household upstairs, which she readily agreed to. She also introduced me to her husband, the resident Vega male in the present generation, who was my helpful informant about the house’s history.

Among other things, the hospitable Mr. Vega pointed out that the citation in Philippine Ancestral Houses that referred to this structure as the “Jimenez House” was inaccurate, and was borne out of the fact that among his distant cousins and property co-owners were sisters Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc (editor-in-chief of the Philippine Daily Inquirer) and Lourdes Jimenez-Carvajal (a.k.a. the late Inday Badiday of showbiz talk show fame). In reality they had inherited their shares in this house not through their Jimenez father, but via their Vega mother.

Going back to the carinderia floor, I ascended these balustered steps

which led to a large landing

which was separated by these indoor windows

from another part of the ground floor, presumably another bodega in the house’s first few decades of existence, now a posh laundry drying area.

The wide and somewhat steep staircase, presumably of ipil, was our next destination.

Its delicately-turned balusters were noteworthy

as were its acanthus-leaf-topped posts

that held up both sides

of the grand approach to the final landing.

This was actually the antesala or foyer, which today is much more modestly furnished than it definitely was originally.

The absence of electricity in the early 1800’s when this house was constructed allowed the builder to ornament the antesala’s ceiling with this modest pinwheel. Or could an oil lamp have originally hung from this?

Another resident of this antesala is this small image of the Nazareno.

The family once owned a large antique processional Nazareno with an ivory head, but this was reportedly stolen a while back. This newer image was then acquired from one of the shops in Tayuman, Manila to somehow, but not quite, make up for the loss.

An emdedded mirror on the left-side wall of the antesala might be a thoughtful amenity for the harried visitor who needs to re-groom upon emergence from the grand staircase – except its current cloudiness will be challenging to work with.

Right beside this ancient mirror is a post, which has hollowed-out panels that supposedly held family artifacts like children’s milk teeth. (What about tonsils, kidney stones, or appendices, I wonder?)

To the left of this mirror and post is the entrance to the original dining room.

There is no longer a dining table here, but the room’s square size and generous dimensions would have easily accommodated a large round table for the presumably numerous members of this wealthy household.

Instead, what remain in here are a late-19th century lansena or sideboard

and an early-20th century platera or plate display cabinet.

Right next to the lansena is the doorway to the first of this house’s four bedrooms, directly above the corner supported by the wooden Crispin Vega outside.

To the left of the entrance to this dining room

is a doorway that leads to the kitchen.

Sadly, the kitchen is in ruins, with a collapsed ceiling, or floor, or both. For everyone’s safety, this door has been sealed.

Back outside in the antesala is another sealed original entrance to the kitchen

and this double doorway that we subsequently find out leads to the house’s third bedroom, more usually accessed from the sala, as we shall later see.

But before that, we identify the second bedroom, directly above the grand staircase, and accessed by this double doorway by making a right-U-turn after climbing the stairs.

Residents of this second bedroom can even get a sneak peek at newly-arrived visitors by peering through these wooden jalousies.

From the staircase and antesala, we go through these double doors

and find ourselves in the Vega Family’s extraordinarily spacious sala, easily amongst the largest I have ever been in in a private home.

This living room is bounded on the exterior by two streets, and is supported at its far corner by the wooden middle son Eusebio. Its vast floor is made up of alternating wide planks of dark balayong and pale tugás (that’s molave or mulawin for us Tagalog-speaking city-slickers).

The ceiling is now non-existent, and according to Mr. Vega was simply never restored after it was damaged by the occupying Japanese during World War II. And the original “pawid” (dried and bundled leaves) roofing, seen here through the rafters, has only been regularly replaced, rather than “upgraded” to terra cotta tile or GI sheets as with most other ancestral houses of the same period.

Mr. Vega also pointed out that in fact, the house was abandoned by the family during the war as they fled the town for their own safety, and when they returned after Liberation, they found the second storey’s wooden floor to be overgrown with weeds! This might explain why quite a number of corners in the sala show evidence of potentially injurious floor damage today.

An interior view also confirms that this house employs “persiana” (wooden louvered) panels for sliding windows, a feature earlier observed from the exterior views seen earlier.

This further confirms the house’s very early date of construction, as “newer” structures (even the 1840 Constantino House in Bulacan, though that might have been remodeled later in its life) would routinely have had sliding windows of capiz shells, or, much later, small colored, frosted, or clear glass panels.

From one such window in the sala, I was able to view a nearby intersection of this very regularly-laid-out residential area of the old Balingasag town center.

Scattered around the sala are various pieces of furniture, including a modern and rather anachronistic bamboo sala set

a 19th century writing table

an early 20th century round table

and a mid-20th century ambassador center table, now missing the rest of the set.

While the sala is now obviously much less richly furnished than how it was during its prime, a clue to it past opulence might be gleaned from this, a beautiful early 19th century long table, with what appears to be a single slab of balayong for its top.

The second bedroom can also be accessed from the sala via these double doors.

And the third and fourth bedrooms are behind these curtains on another sala wall.

Here’s the double doorway to the third bedroom:

And the interior view of the fourth bedroom’s doors is this:

Like those in most Philippine ancestral houses, the Vega house’s four bedrooms are small by 21st century “wealthy-home” standards. The fourth bedroom only had space for a narrow double bed, and this circa 1950’s ambassador sofa:

While it probably helped ventilation somewhat that a hole was cut high in the wall between the third and fourth bedrooms

it couldn’t have been good for privacy – though our 19th century relatives were apparently not as sensitive about that as we are in the 21st century.

And I didn’t even notice where this house’s “facilities” were located!

We then make our way back to the sala, out into the antesala, and down the grand staircase

as we thank our gracious Vega Family hosts for letting us into their most venerable two-century-year-old home. And prepare for more excursions into this hidden gem of a heritage-home-junkie target of a town.

Continued here.

All text and photos, except as otherwise indicated, copyright ©2008 by Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

No comments:

Post a Comment