All good things must come to an end (ugh! – where do these clichés come from?), and so must our Vigan visit. (End, that is.) Fortunately, there are still other interesting places that we can go to on our way out of the city. For starters, right beside Vigan, on the other side of the city’s prominent welcome arch, is the town of Bantay Sur.

The bell tower is one of the few in the

One may ascend the tower via an extremely steep and narrow spiral staircase, something that would probably increase one’s insurance premiums significantly. All that you get for all that risk and effort is a lot of strong wind at the top (not fun unless you enjoy standing inside a wind tunnel), bits of trash left by previous tourists (apparently some people like to picnic up there), and abundant graffiti courtesy of the local teens. Far more interesting is an examination of the tower’s structure – innumerable red bricks, perhaps from a colonial-era kiln in the area that must have also supplied building material for the Vigan ancestral houses.

There are only five places in the Philippines Vigan Iloilo Santa Maria Manila

The

\These steps and the church at the top were immortalized in a famous Fernando Amorsolo painting, “Binyag ng Panganay” ("Baptism of the First-Born"). Since I don’t own that painting (or any Amorsolo for that matter), just imagine a young couple with a newly-baptized infant at the foot of the steps in this next shot, more or less:

We continue our climb, and the all-brick (from the same Vigan-area kiln perhaps?) church starts to fill up our frame of sight:

One of the unusual things about the Santa Maria church, which some might have noticed in the first photograph of the staircase above, is that its convento (parish house) is in front of the church, rather than attached to its side. Here’s how it connects to the front of the church, via a catwalk that doubles as a gate and fence:

It would have been really good to do an akyat-bahay visit of this apparently early-20th century structure, but as the photos above make evident, it is closed – its gates, doors, and windows were all firmly shut when I was there. It appeared to have been abandoned and in disuse, perhaps for reasons of operating economy.

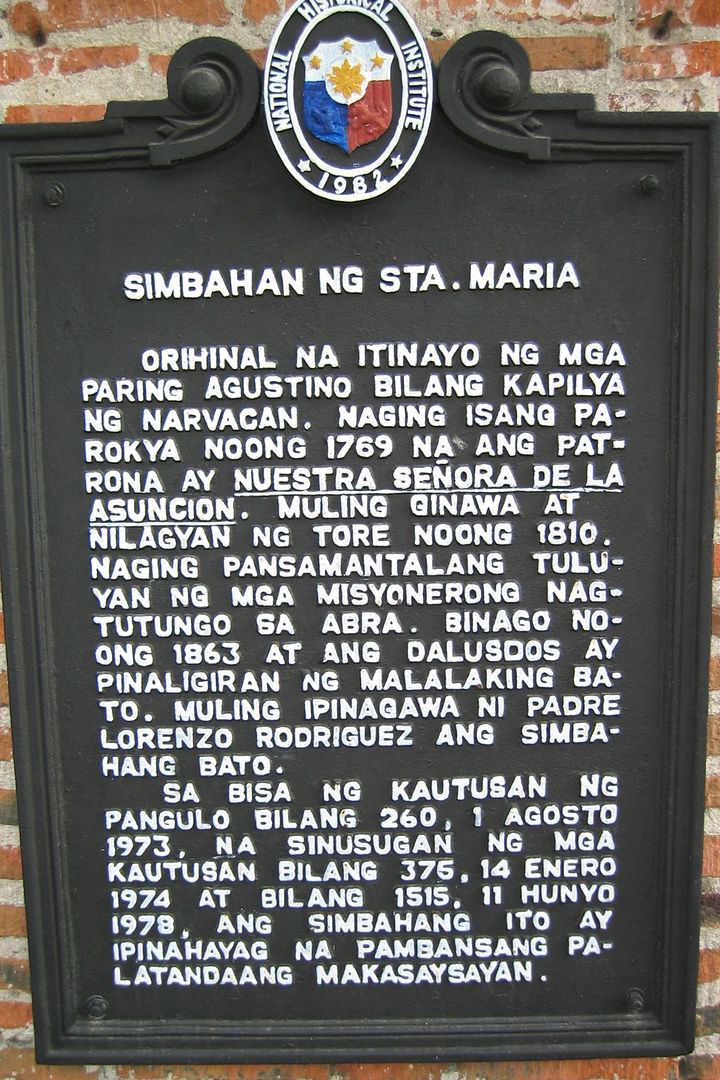

Instead, we walk back to the church and see a historical marker by the main door, which is helpful:

For the bilingually-challenged, it says that the

Since the main door is shut, we instead go to the side of the church and view the length of the structure, defined by thick stone buttresses. They’re obviously not as elegant-looking as Gothic-style flying buttresses, but they’re what give the walls the structural strength necessary in this part of the world, hence the name of the style that the four aforementioned Philippine churches supposedly share – “earthquake baroque.”

Before we walk down that inviting path, we take a look at the church’s bell tower, like Bantay's a rare separate structure from the church, and which, as the historical marker said, was built in 1810:

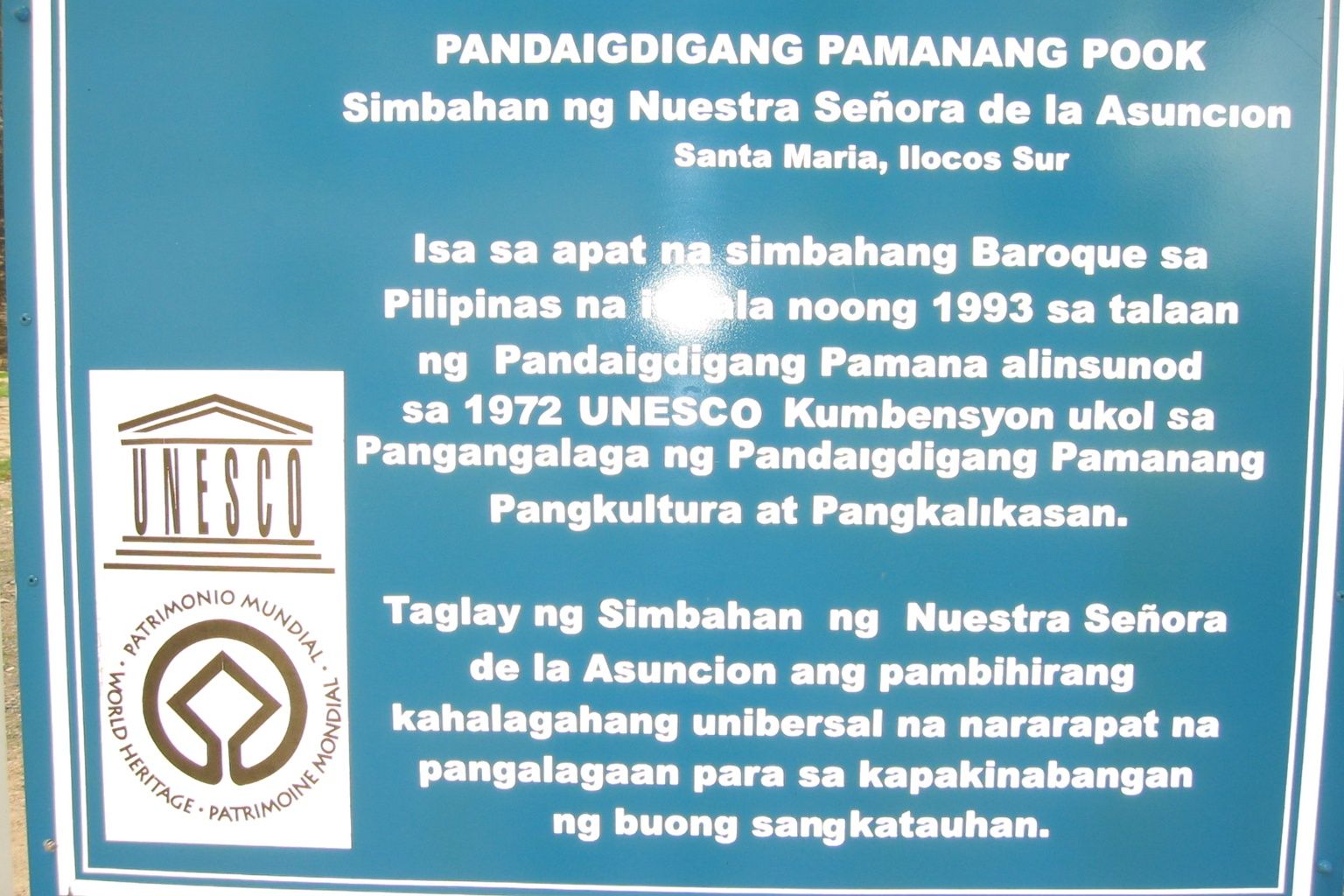

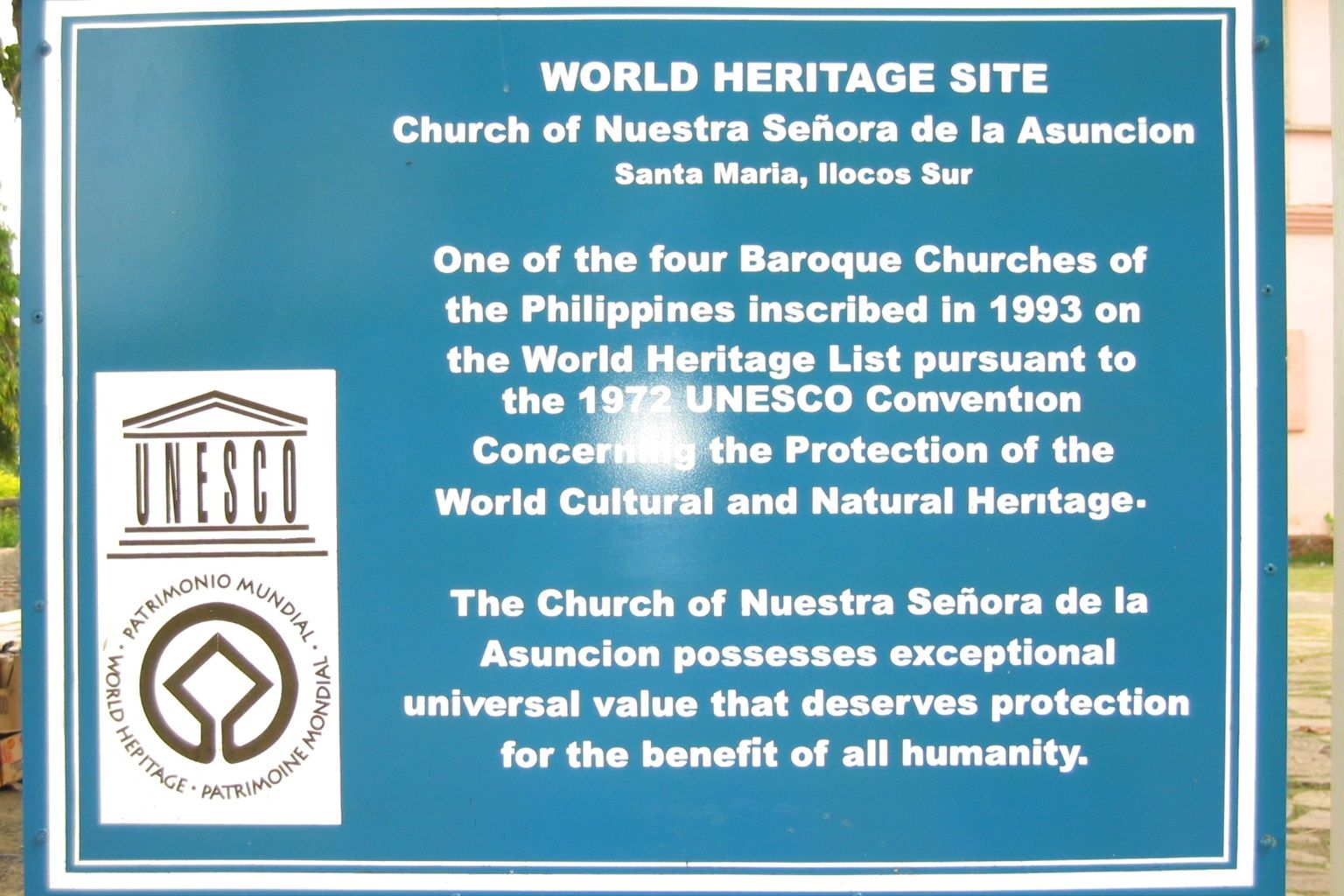

Sharp-eyed readers would have noticed an incongruous light blue-colored thing in front of the bell tower in the earlier photo. That is actually the UNESCO World Heritage Site marker itself, which we walk up to to take a closer look:

For the bilingually challenged, these standard UNESCO markers already come properly translated on the reverse:

And when we get to the end, we stop and look in the other direction. (After all, “Ang hindi lumingon sa pinanggalingan ay hindi makakarating sa paroroonan.”)

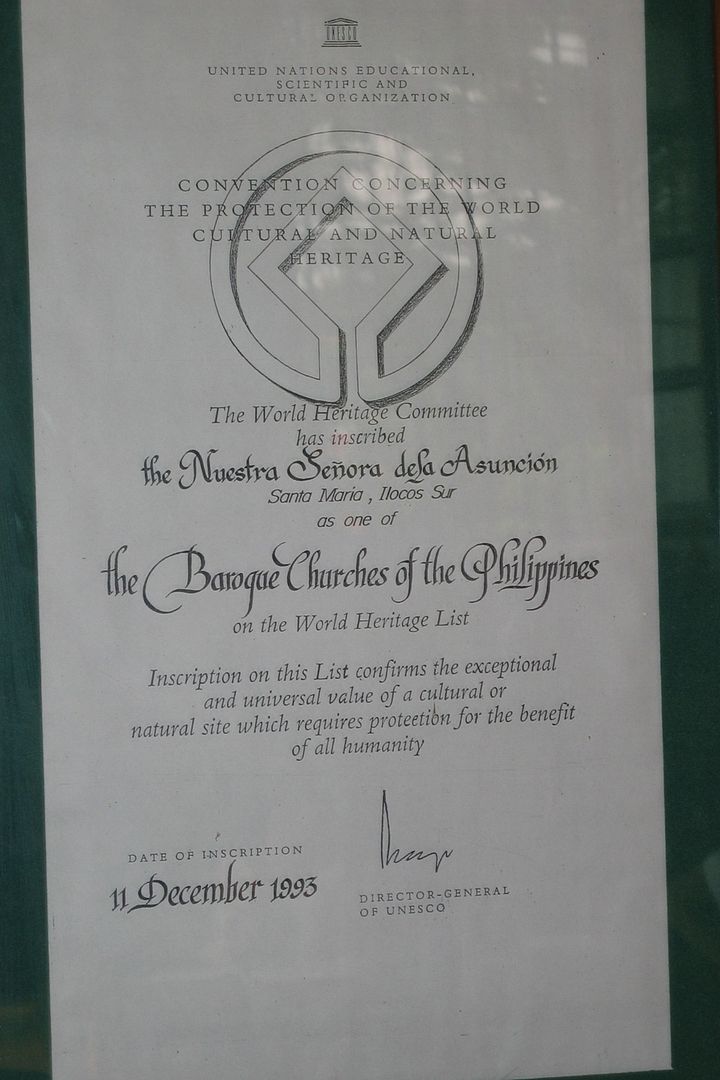

on the ground floor of which is the parish office. In this office is the actual certificate of the church's inscription into the World Heritage list:

The parish office connects to the sacristy, which allows us to enter the church. Despite the bright afternoon sun outside, it’s awfully dark inside,

making it very difficult to note specific interior details and examples of religious art. But looking towards the main altar, we notice that it is partly lit,

and we move up closer to get the best possible (under the circumstances) view of the image of the town’s patron, Our Lady of the Assumption:

More accessible is a side altar, on which is placed a full-sized clothed image of Christ the King, complete with crown and scepter, and perhaps unusually, standing rather than seated on a throne:

Going back outside to the rear of the church, we espy a partly-tree-lined clearing on the other side of the church.

But just like the old convento, this area is off-limits and is fenced off from potential trespassers like me.

Instead, we then walk back to the front of the church, and descend the 1863 staircase back to the main road.

Thus ends our perhaps slightly uneventful and anticlimactic visit to one of the four Philippine churches on the World Heritage list. But this only means that we need to try to visit the other three. Memo to self: Add to to-do list.

2 comments:

That's a beautiful place! - Sakit.info

Thanks for reading and for the appreciation!

Post a Comment