After

visiting the 1873 Noel House in Carcar, I subsequently found out that it had a

nickname, “Ang Dakong Balay” or “the big house”, and of course that was entirely

appropriate as we had seen. My next

Akyat-Bahay object in town was just down the road, and I had already established

that it was better-known that the Noel House, having previously read about it

in the popular press and online. This

was the “Balay na Tisa”, named for its original terra-cotta clay roof tiles

that are still in place as the structure’s roofing material.

What

I next discovered was that while it was certainly not as large as “Ang Dakong

Balay”, it was even older and is in fact the town’s oldest stone structure,

beating even the church and other public buildings. It was originally built by spouses Roman

Sarmiento and Ana Canarias in 1859. In

fact, the house’s side yard fence was decorated with tarpaulins commemorating

its then-recent milestone 150th anniversary.

Don

Roman had been Mayor of Carcar even before the house was built. His and Doña Ana’s great-great-grandsons,

cousins Manny Castro and Marc van Zwoll, are the house’s present-day custodians

and guardians.

If

the house looks somewhat squat from the outside

compared

to other surviving specimens from among its mid-19th century

contemporaries in other Philippine towns, that’s because the street fronting it

had been raised significantly over the last several years,

in

the hope of beating the rising flood levels during the rainy season (climate

change, no doubt), which probably isn’t helped by the fact that the seafront is

just a kilometer away.

But

while this road surface elevation may have kept the street itself flood-free

(or so it was hoped), the structure itself obviously remained at the same

elevation, as evidenced by the ground-floor’s windows now half-buried

and

the original main entrance, now primarily suitable for midgets.

Rather than risk hitting our pointy head against the door jamb, we make our way to the side of the house, left of the façade, and along the perpendicular road (as the house is situated on a corner),

through

a pedestrian gate,

that

leads to the house’s backyard.

We

look for the backstairs

that

leads up to the well-greened azotea

and

through to the kitchen

which

was very spacious indeed.

Before

proceeding further with this Akyat-Bahay visit from the back of the house

towards the front, I attempt to remedy this upside-down situation somewhat by

finding my way to the ground floor of the house, which I could not access

earlier via the too-short (and actually shut) front door from the street. I locate the house’s main staircase near

where the living room must be

and

descend it.

The

wooden stairs ends in a stone landing,

from

where I am greeted by a flooded ground floor.

The

entire zaguan of the house is now below the usual ground water level,

consistent

with our earlier discovery of the much-raised street that fronted the house, a

tangible effect of climate change.

Certain sections of the floor have been elevated, such that they were

relatively water-free even if other portions were not. But everything had still been raised on

stilts as a further precaution especially during the more flood-prone rainy

months.

Thus,

armchairs are mounted on concrete blocks

or

are placed atop antique beds, which are then also mounted on blocks.

Much

of the rest of this zaguan was organized this way.

An

interesting-looking Visayan-style altar table on which is placed a small Holy

Family ensemble within an urna avoids having to be elevated, but maybe only

temporarily.

On

a well-elevated stump on one side are stacked several batibot chairs, avoiding

rust-inducing flood waters, and ready to use for when the house hosts more numerous

visitors.

Even

what is presumably the homebound calandra of Carcar’s Santo Entierro is

elevated on stands, though that would probably be the case even if it were not

in this flooded basement.

Unfortunately,

the house’s venerable antique upright piano had not been saved from previous

flooding, therefore its lower portion appeared soggy.

Perhaps

a skilled restorer (of which there are a number in Manila) might be able to

rehabilitate this and make it playable once again.

A

slightly (though not completely) drier section of the space was set aside for a

religious art exhibit

A

closer view reveals that the featured artworks all (or mostly) depict Saint

Catherine of Alexandria, Carcar’s patroness.

Before

going back upstairs, we look for the doorway that goes out into the street in

front.

Consistent

with its shut appearance from outside, it appears to be securely barred from

within, which is just as well as it is separated from us by a pool of flood

water.

Window

openings are also securely barred

or

iron-grilled

even

if they only lead to other sections of the zaguan.

We

find our way back to the main staircase, past the distressed antique piano

and

eagerly climb back up to the main storey

and

away from the somewhat dank and damp squalor below.

We

reemerge onto the caida or antesala, which we had obviously passed through

earlier on the way downstairs, but this time we take our time and note the

profusion of artifacts and furnishings around, including side chairs and settees tucked in behind the

balustrade,

an

Art Nouveau light fixture illuminating the stairwell from above,

and

numerous artworks, many depicting the house from the outside.

Inserted

among the artworks was an old and blurry photograph of what I’m guessing is a

very tall and elaborate processional calandra,

presumably

transporting the resident Santo Entierro image (when not ensconced in the

domestic calandra that we had seen earlier on the ground floor) on a Good Friday

many decades ago. (I wonder where it is

kept though these days?)

A

small-scale three-dimensional model of the house doubles as a donation box.

From

this antesala, we take the doorway towards the front part of the house, through

elegantly-crocheted curtains,

which

passage looks like this from the other side, revealing a handsome set of

arch-topped double doors.

We

now find ourselves in the expansive, abundantly decorated, and naturally

well-lit sala.

This, the house's principal room, is furnished with every variety of furniture from the 19th century, from Visayan-style comodas

to

butacas

to

divans-daybeds

to

altar tables.

There

was even a mariposa divan, with not just solihiya upholstery but also pillows

and cushions.

More

conventional upright seating was also available, either beside a small

occasional table with an Art Nouveau lamp and picture frames

or

next to a musical instrument.

The

sala was also artificially lit with appropriate period fixtures,

hung

from what appears to have been an original metal ceiling,

and

the walls were covered with Art Nouveau-framed ancestor portraits.

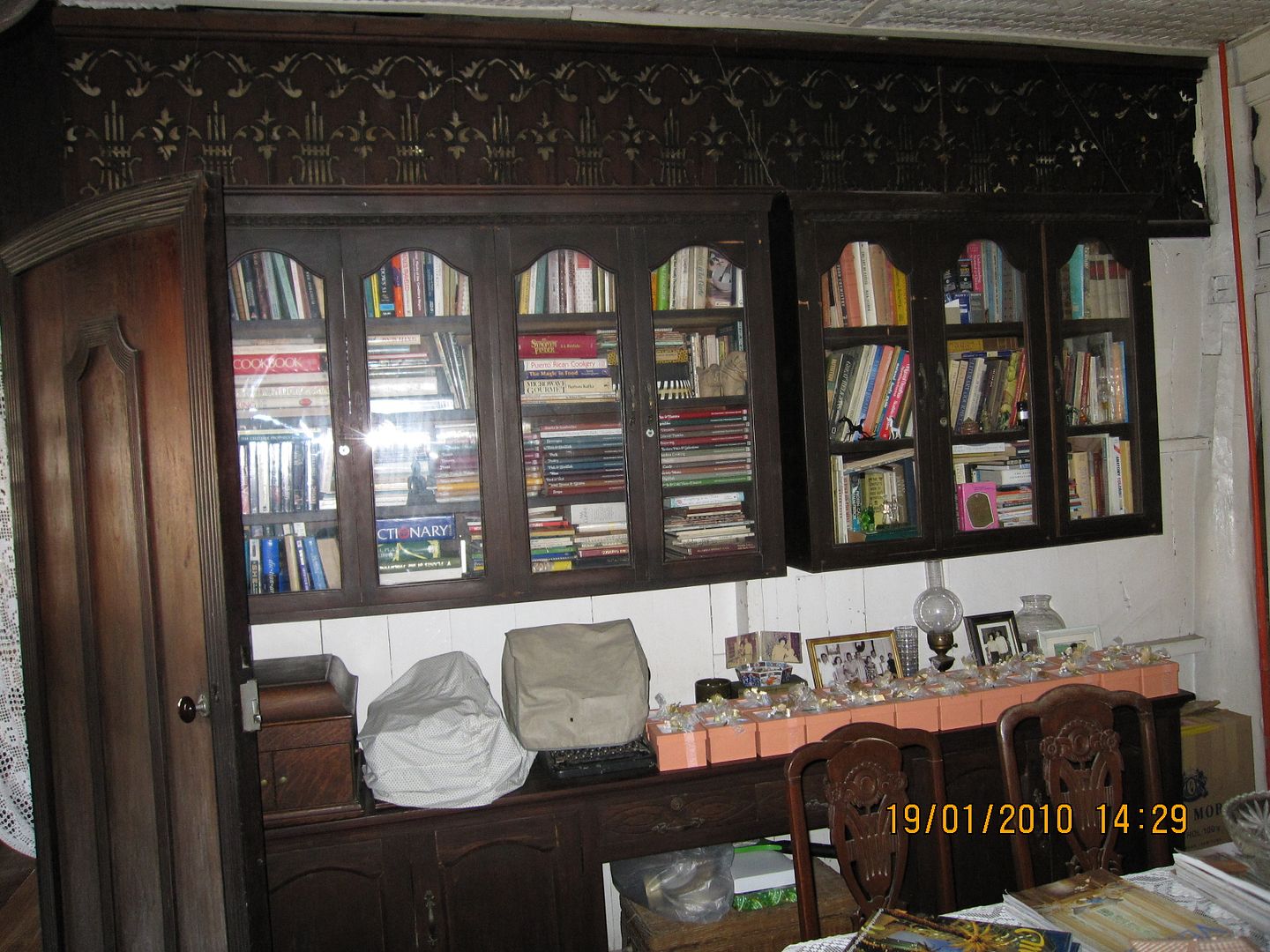

Adjacent

to this sala was the original master bedroom, accessed via a doorway with more

crocheting.

This

room is now a home office or study, with a work table,

hanging

book cabinets,

additional

storage, courtesy of a pair of comodas,

a

writing area in a quiet corner,

and

a fully-upholstered sitting area.

The

room still had what appears to be its original sawali (matted bamboo) ceiling,

or a more recent but identical replacement, from which was suspended an

electrified “globo” lamp.

This

private study, like the living room, bordered the main street fronting the

house, therefore the glare and noise had to be managed via half-paneled

half-louvered window panels and more crocheted curtains.

We

make our way through the crocheted doorway

back

to the sala

and

back out to the antesala, and through the doorway on the opposite side.

It

was not really a normal doorway, more like an opening in the ornately pierced

wall of the antesala.

This

led us to the large dining room, nearly as generously sized as the sala.

The

space was furnished with several seating areas, including a round table for six

and

a rectangular table for eight

with

two armchairs and two benches.

If

these seating areas were insufficient, there was auxiliary space via small

rectangular tables, benches, and side chairs

positioned

symmetrically on either side of a row of windows

and

bisected by a small round table.

Any

remaining room space was given over to further table settings

to

enable the household to show off its extensive collection of artifacts

including

a tall floor-standing candelabra.

Further

collections were housed in vajilleras (crockery cabinets)

or

plateras (plate cabinets)

of

which this dining room had at least three.

Adjoining

this dining room were two identical crochet-decorated doorways

that

led to the house’s two proper bedrooms.

Since

only one bedroom door was open and available to be entered (perhaps the locked

neighbour actually now held the precious Santo Entierro?),

I

just presumed that they were near-identically furnished

with

canopied beds,

mirrored

as

well as tambol (wood-paneled) aparadors,

a

divan by one side,

and

a comoda as a nightstand.

In

one corner was a narrow communicating door to the other (locked) bedroom.

By

this point, the remaining part of the house that we had not yet examined

closely

was

the kitchen out back.

As

we had briefly observed earlier on our way from the outside, it was spacious

and airy.

It

was also tastefully yet practically furnished, with period-appropriate

equipment including a paminggalan with decorative inlay, unusual for such a

utilitarian piece of furniture,

and

a work table with beautifully reeded legs.

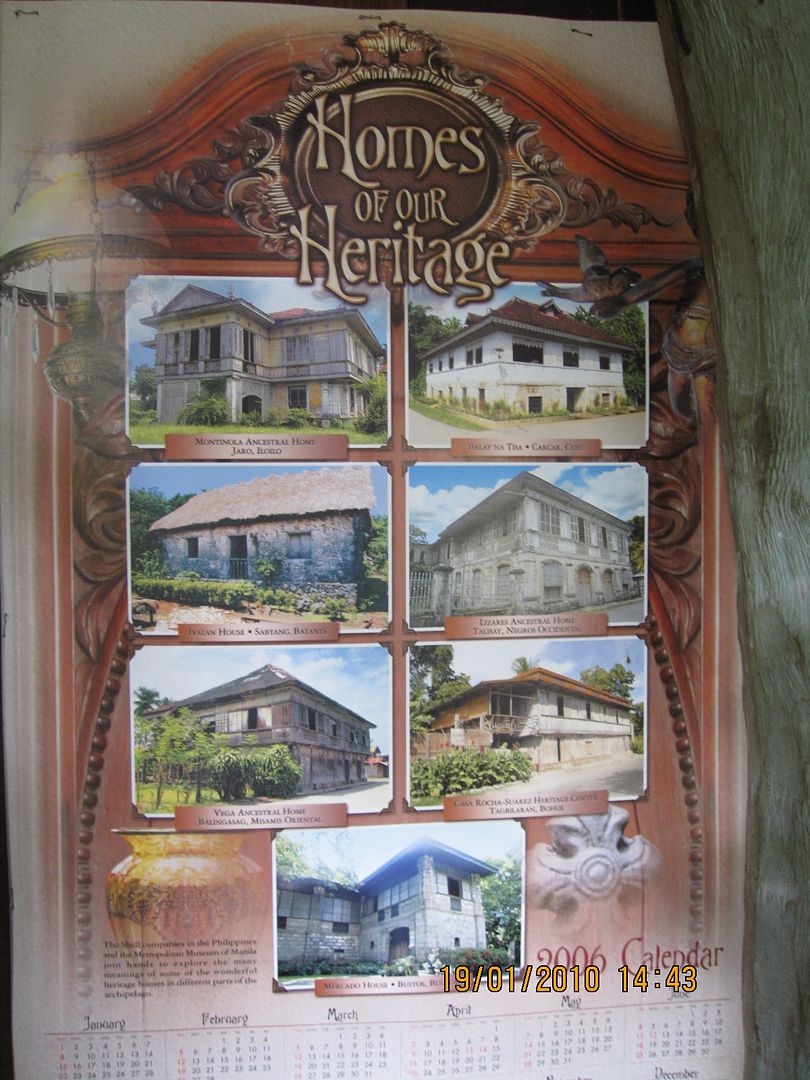

On

one wall hung an obsolete calendar, now merely a poster, featuring several ancestral

houses; our current host is in the upper right.

This

large kitchen space, like the study adjacent to the sala that we had seen

earlier, has a sawali ceiling, from which is suspended a beautiful cast iron

light fixture.

Further

rearward via this passage

is

the azotea

which

is a nice little oasis of green.

In

another direction, past this doorway

are

the house’s “facilities”

which

are even properly labelled.

From

this corner of the back, we can look out towards the front of the house along

the side and appreciate the crawlers adorning the bedroom windows.

And

we’ve also seen earlier from when we entered the house from back here that this

end is nicely populated with greenery.

Which

brings us back to where we started, and thus the end of this visit, to Carcar’s

oldest extant structure.

Originally published on 24 July 2018. All text and photos (except where attributed otherwise) copyright ©2018 Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

Originally published on 24 July 2018. All text and photos (except where attributed otherwise) copyright ©2018 Leo D Cloma. The moral right of Leo D Cloma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.